This is a legacy story from an earlier version of our website. It may contain some formatting issues and broken links.

One of the most interesting aspects of our work at Brighton History Centre is answering enquiries from members of the public. These range from the very specific to the more general. We might be asked, for example, when the houses in a particular street were built, or who designed the city’s Victorian schools. Or, perhaps, how Brighton was affected by the coming of the railway.

Charles Dickens Farewell Tour

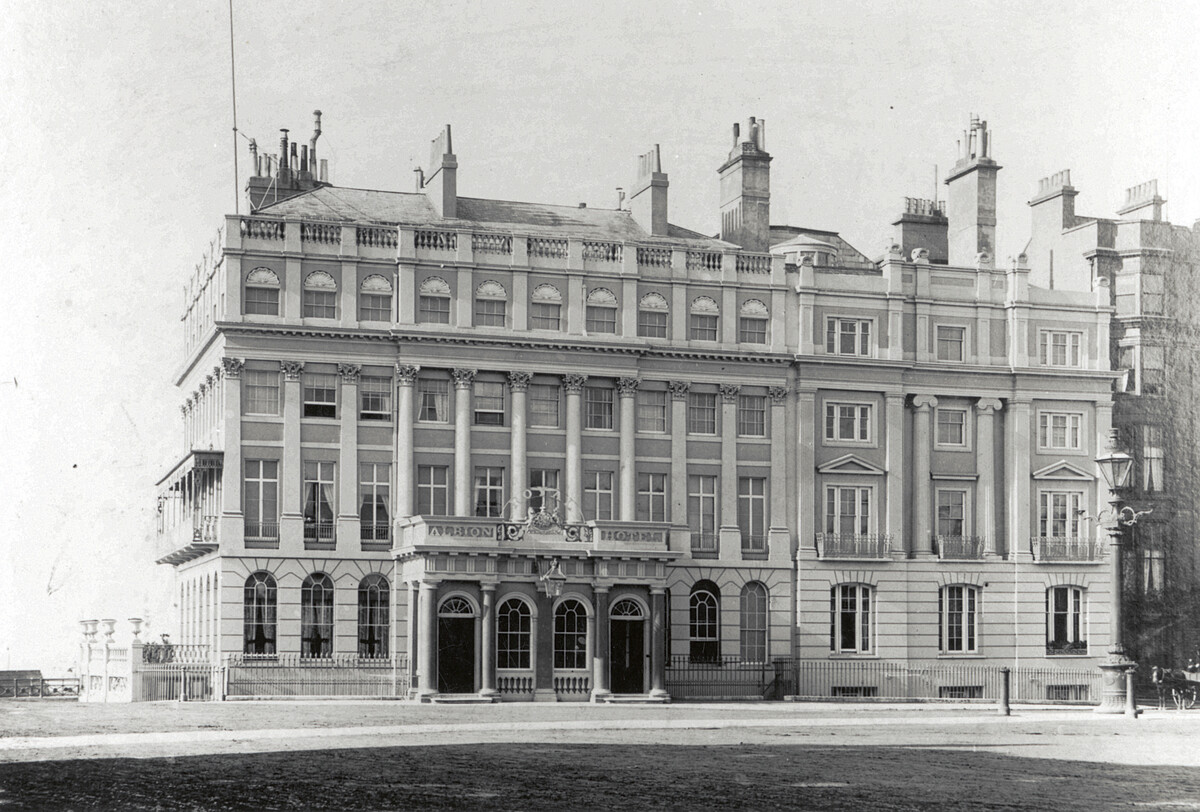

Recently, we were asked if we had any information about Charles Dickens’ links to Brighton. How often did he come here? Where did he stay? It seems Dickens was a frequent visitor, coming first in October 1837, around the same time that Queen Victoria was making her first appearance in the town. Unlike Victoria, Dickens obviously liked what he saw and came back repeatedly over the next 30 years, staying in a variety of places on the seafront. The Bedford Hotel seems to have been a particular favourite, but he also ‘put up’ at the Old Ship Hotel and, from time to time, stayed in private lodgings with friends and family.

On one occasion, he and his entourage, which included the illustrator John Leech, were forced to flee their rented accommodation because the landlord and his daughter apparently went quite mad. Dickens described the scene vividly in a letter to a friend: ‘If you could have heard the cursing and the crying of the two, could have seen the physician and nurse quoited out into the passage by a madman at the hazard of their lives; could have seen Leech and me flying to the doctor’s rescue…you would have said it was quite worthy of me…’

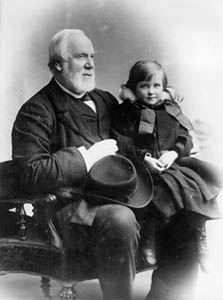

While parts of Bleak House and Barnaby Rudge are said to have been written in Brighton, the novel that has the closest connection with the town is Dombey and Son, first published in monthly parts from 1846. In it, the young Paul Dombey, a frail and sickly child, is sent here by his father for the good of his health. He and his sister Florence lodge with Mrs Pipchin, whose home ‘in a steep bye-street at Brighton’ is thought to be based on a house in Upper Rock Gardens, and he is sent to Dr Blimber’s academy, which was probably inspired by one of the many private schools for young gentlemen that operated here at that time.

In later years, Dickens came to town for readings of his works, which always attracted a large and fashionable crowd. After one event at the Town Hall, Dickens wrote, ‘Last night I had a most charming audience for [David] Copperfield, with a delicacy of perception that really made the work delightful.’ In 1868, Brighton was included as part of his ‘farewell tour’, and again, each performance was hugely popular – a report in the Brighton Gazette describes ‘a room full to repletion’ at the Grand Concert Hall, where ‘the dialogue throughout was delivered by [Dickens] in his liveliest and most felicitous manner.’

For more information about Brighton History Centre’s Research Service, please refer to our website. To see images of Brighton Museum & Art Gallery’s Dickens-related objects, posted to commemorate the anniversary of his death in June 1870, vistit Flickr.

Kate Elms, Brighton History Centre