This is a legacy story from an earlier version of our website. It may contain some formatting issues and broken links.

Paula Wrightson follows the owners of Preston Manor on a tour through Egypt at the start of the twentieth century. Through a photograph album held at the manor, she traces their route across the country at a time when the height of British imperial power met the death of the Victorian era.

In November 1922 British archaeologist and Egyptologist, Howard Carter wrote a now famous telegram from the Valley of the Kings in Egypt to his patron back home, the 5th Earl of Carnarvon, “…at last have made a wonderful discovery…” revealed as the fabulous treasures of the Tomb of Tutankhamun.

Photograph album Egypt 1900-1901

96 years on I received an email from a member of the Sussex Egyptological Society who had made a wonderful discovery of her own whilst on a visit to Preston Manor.

“…Being of a curious nature” she explained in the Society’s newsletter, “I was peering through the glass doors of the bookcases in their library to see what sort of books the family had collected, when a certain title caught my eye – “Egypt”. On closer inspection, it looked much like a photo album…how excited was I?”

Members of the Sussex Egyptological Society requested a viewing of the albums, of which there are three dating to 1901. Following the Society’s visit to Preston Manor I learned a great deal from their expertise.

Visiting Egypt in 1901

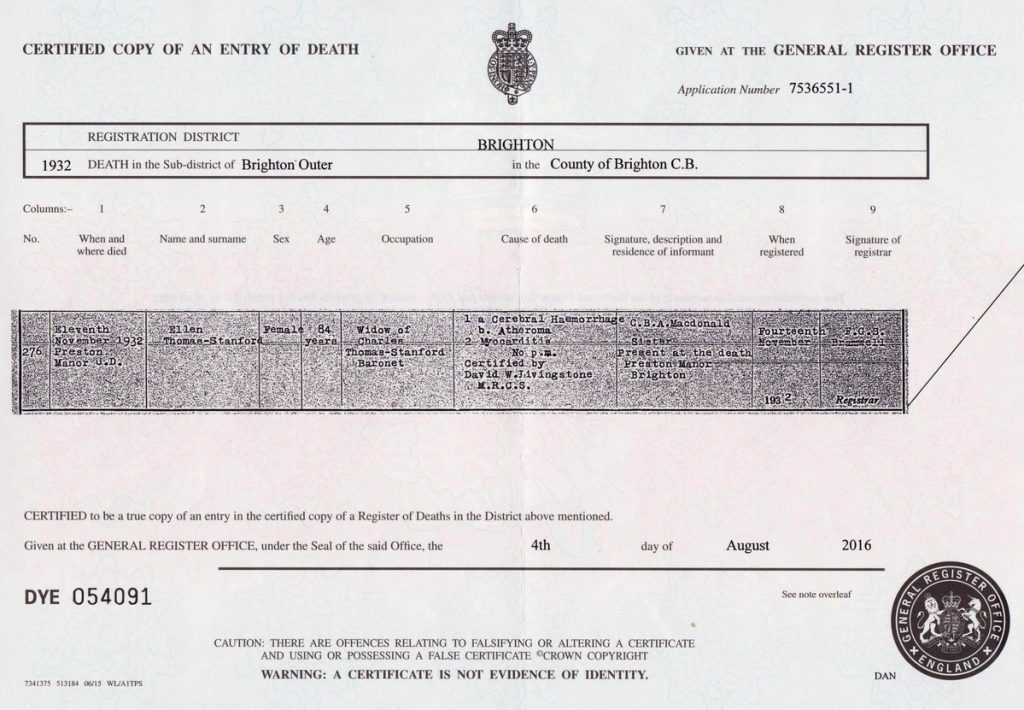

Charles and Ellen Thomas-Stanford went to Egypt as sightseers. although Charles’s passion for archaeology meant he would have taken a more academic interest in the places they visited than most tourists.

Egypt was a popular destination for cultured Europeans. The British travel agency, Thomas Cook Ltd, opened its first head office in Cairo in 1872. By 1900 it is estimated that as many as 50,000 tourists a year were visiting Egypt with a cruise along the Nile River an essential experience. The Thomas-Stanfords enjoyed every luxury. Travellers were provided with the comforts of home on board well-appointed steamships and in opulent hotels.

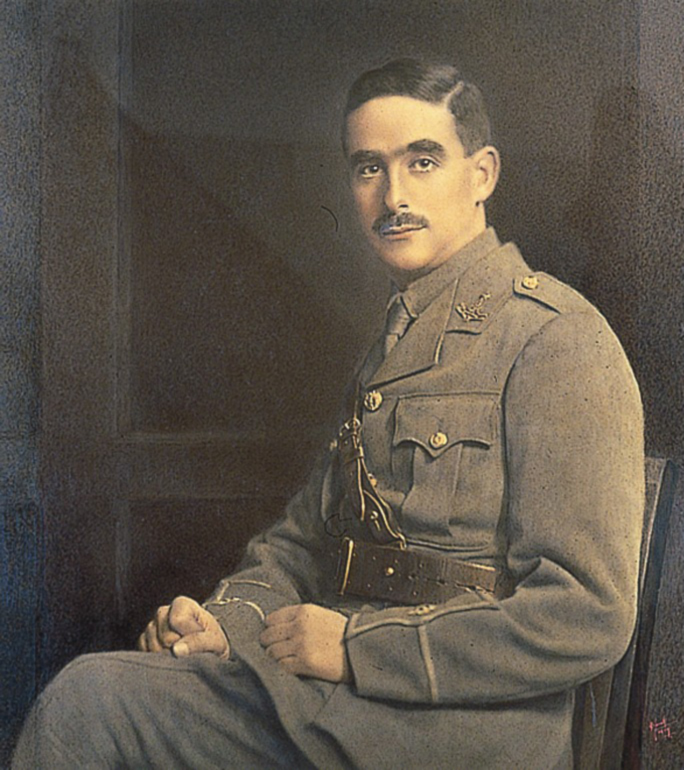

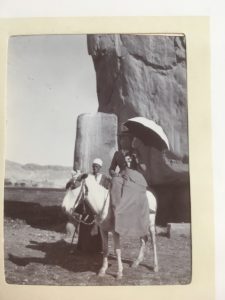

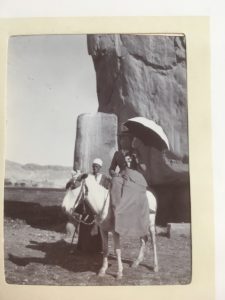

Ellen Thomas-Stanford dressed for her trip through Egypt

In 1901 you needed wealth and leisure to visit Egypt along with the ability to withstand a hot climate in your many-layered clothing; in Ellen’s case, this would have also included a tightly-laced corset. Photographs show Charles and Ellen in conventional European dress. Charles’s suit would be summer-weight linen and Ellen carries a parasol. In all other sartorial respects the couple appear dressed for the January they left behind in England.

It took between five and ten days to travel from Britain to Cairo. The couple almost certainly stayed for a while in Cairo acclimatising to temperatures equivalent to a hot summer’s day in Britain. They probably spent Christmas and New Year enjoying the home-from-home delights provided for the large British community: a Savoy Hotel, an All Saints Church, the Turf Club Jockey Club and lawn tennis clubs where friends might be met.

Health and wealth

Today visitors are required to be vaccinated against a range of diseases before travelling to Egypt. Charles and Ellen had no such protection although, as they were born in 1858 and 1848 respectively, they would have been vaccinated against smallpox in childhood due to the Vaccination Act of 1853 that made vaccination compulsory.

In anticipation of ill-health wealthy European travellers to Egypt might take a medical doctor as a member of their party but Thomas Cook’s network of tourist stations along the Nile provided doctor’s surgeries as well as post offices and other conveniences.

In 1891 Cooks Tours Ltd were running 24 steamers on the Nile running to an enormous £82,000 annual net profit by 1900. For the tourist a three-week trip cost £50 a head, an amount equal to a year’s wages for a skilled working man.

Watercolour painting, the Great Colonnade in a Temple at Philae by CharlesBarry

At home with Egypt

For the devout Victorian-born person Pharaonic Egypt linked comfortably with Biblical texts, making a visit something of a pilgrimage. Egypt was familiar from church readings on Sunday and consequently a place one felt acquainted with.

The Edwardian-born poet John Betjeman evoked a cosy domestic glimpse of an English-at-home bond with Egypt in his 1941 poem ‘The Subaltern’s Love Song’ in which a lovelorn Englishman awaits his sweetheart, Joan Hunter-Dunn at the foot of the stairs in a suburban house in leafy Surrey, his Hillman car purring in the driveway.

The Hillman is waiting, the light’s in the hall,

The pictures of Egypt are bright on the wall,

My sweet, I am standing beside the oak stair

And there on the landing’s the light on your hair.

If you stand on the landing at Preston Manor you will step into this stanza for there are four such pictures of Egypt to be seen. Three watercolour paintings show scenes on the Nile and one a ruined temple. These exotic images sit incompatible yet at ease alongside solid mahogany bookcases, Sussex longcase clocks and a rustic copper warming pan.

A further glimpse of Ancient Egypt can be seen on the mantelpiece in the library: a pair of spelter candlesticks in the form of Egyptian figures. These are British-made c.1880.

Egyptian inspired clock c.1807

The early years of the nineteenth century saw a growing interest in the art and architecture of Ancient Egypt fed by the Napoleonic Campaigns in Egypt 1798-1801. Ancient Egypt flourished as a theme in European tombs and mausoleums, garden follies, statues, clocks furniture and jewellery. If you visit the Kings Apartments anteroom in the Royal Pavilion you will see some fine examples of Egypt-inspired decorative objects from that period.

The Thomas-Stanford’s Dragoman

Crucial to travel in Egypt in 1901 was the Dragoman. He was a local guide, translator and interpreter, and a general tour organiser fixing accommodation, food, travel and everything else. Dragoman is an interesting word; derived from the Arabic tarjumān. The Dragoman to the Thomas-Stanford party is named as Ahmed abd-el Sadek in the album.

“Our Dragoman” Ahmed abd-el Sadek

He is photographed in Luxor standing against a white-painted wall on which the shadow of a palm falls in the bright sunshine. He wears a close-fitting white cap and long layered robes. The cuff of his outer robe has a silken appearance and is ornately flared. Just visible his hand holds a fine polished cane, a stout stick he no doubt found many uses for. Ornate too the low collar of his inner robe. His middle layer appears to be a European man’s linen jacket. Hanging from a button the chain of a pocket watch can clearly be seen. Ahmed abd-el Sadek has a well-planned itinerary to keep and timing is important.

He looks about 30 years of age and knowing the Thomas-Stanford’s wealth he was the best Dragoman available, a man of wisdom and experience. He would have spoken English and French as well as local languages. I asked members of the Sussex Egyptological Society about life expectancy in Ancient Egypt and they told me people lived to no more than about 40. Further investigation shows average life expectancy in Egypt in 1960 reached only 46. Our 1901 Dragoman is in his mature years.

Photographing Egypt

The Thomas-Stanford’s Kodak brand photograph album

The party travelled from Cairo to Aswan and into Nubia, taking photographs along the way. I don’t know what camera they used. In 1900 the first Eastman Kodak Box Brownie camera came on the market and this was ideal for lightweight travel. Two of the photograph albums are Kodak branded so it is likely the camera was too.

Roll film in 120 format was introduced in 1901 allowing up to 15 shots per roll. This new affordable camera marketed under the slogan ‘you press the button – we do the rest’ made informal ‘snapshots’ possible, and looking through the Thomas-Stanford’s albums this is what the pictures are.

Ellen Thomas-Stanford was a keen photographer in her own right. The 1925 inventory of Preston Manor shows a bathroom containing an egg-timer and magnifying glass indicating its use as a photographic darkroom. However, in Egypt Ellen clearly isn’t engaged in artistic picture-making. She is snapping the sights and grabbing shots of the modern day Egyptian people going about their daily lives.

The Sussex Egyptological Society reports “the first album was mainly street scenes of the local people, donkeys and camels laden with their burdens; also lots of feluccas on the Nile….the second album was a sheer delight. At Cairo were the Giza pyramids with the Sphinx emerging from the sand. At Luxor there were recognisable photos of Medinet Habu, the Ramesseum, Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple, the Colossi of Memnon, Luxor and Karnak Temples….”

A street scene in Cairo; men and boys working a weaving loom

The British in Egypt

Looking online at a Cook’s Nile Itinerary of 1897 I am tempted to believe the Thomas-Stanfords booked a Cook’s tour in 1901 for the sites they visited and thier photograph correspond exactly. Beginning in Cairo the trip along the Nile included 29 destinations including Thebes, Luxor and Karnak finishing in Wady-Halfa in northern Sudan.

For Ellen Thomas-Stanford entering Sudan must have been especially thought-provoking because her son, John Benett-Stanford, had been in the country in 1898. John’s objective was military not leisure, for he was there as a war reporter, He famously taking moving film footage of the Battle of Omdurman, although the footage is now lost..

Today travellers are advised to research the political situation in their holiday destination. What could the Thomas-Stanford’s expect in the region considering the grim toll at Omdurman happened only three years before?

In 1901 the couple would have spent their holiday secure in the knowledge that nearly a quarter of the globe was British-ruled, for this was the age of Empire linking far-flung places with home under one uniting flag.

Trading scene at Esna on the Nile south of Luxor

However, in this age of colonisation the French were most active inNorth Africa, and if you look at photographs of Cairo in 1900 the streets could be fashionable Parisian boulevards. Egypt changed colonial hands following the recall of the French fleet prior to the Bombardment of Alexandria during the Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882. From this time the British governed Egypt in a period called the ‘veiled protectorate’. Officially the country operated as an autonomous province nominally under Ottoman rule but British officials held power controlling Egypt’s government, armed forces and finances.

Charles and Ellen Thomas-Stanford would have viewed the British in Egypt as fairly and squarely in charge. Possibly they knew Evelyn Baring, the 1st Earl of Cromer who held the positon of Consul-General of Egypt from 1887-1907. Cromer (of the Barings Bank family) was adept at putting British interests first, the chief of which was control of the Suez Canal (constructed 1869). Likewise, Cromer exerted power in Egypt quite literally by harnessing the waters of the mighty Nile, the people’s most vital resource, by instigating construction of the Aswan Low Dam.

The Aswan Low dam under construction

Visiting the Aswan Low Dam

Built between 1898 and 1902 the works were on the tourist route and so the Thomas-Stanfords made a visit. There are three photographs taken on the construction site – and it is remarkable how close visitors could get to the workmen. Three westerners, seen from the back, are clearly visible in one of the photographs; the woman with a parasol (possibly Ellen Thomas-Stanford) is walking a long boardwalk laid aside the works.

A John Aird and Co truck on the Aswan Low dam construction site

Record-breaking for scale at the time, the dam was designed by Sir William Wilcox, a British civil engineer. The work contracted to John Aird employing local labour. An Aird and Co railway truck can be seen along with steam-powered cranes. In 1901 no one wears a hard-hat or protective work wear. Men work clad in their ordinary everyday clothes, the long shirt or gallibaya and cover-all kaftan hitched up for ease of movement. Every man’s head is covered by hat, cap or turban. The photographs are very small (7 x 9cm) but on close inspection the men wear soft shoes on bare feet whilst working with huge blocks of stone in a quarry-like building site.

A steam train down the Nile

For the most southerly leg of the journey the Thomas-Stanford party travelled by train as a photograph labelled, ‘the railway station at Shellal’ attests. In 1901 a state-run railway system operated along the Nile valley from Cairo in the north to Aswan in the south (opened 1874). The section of line from Aswan to Shellal was narrow gage and built in 1884 for military purposes.

In the photograph a woman in western clothing stands with her back to the camera on a humble platform piled high with trunks, suitcases and bags. A tourist sign gives fare prices and a shop front advertises tobacco. For some of the journey the party certainly took a Nile steamer but their weighty luggage likely went by train, hence the need for their Dragoman’s pocket watch.

The railway station at Shellal

Philae and Abu Simbel temples

The Thomas-Stanfords took twelve photographs of the Temple of Isis complex at Philae which in 1901 was situated on an island in the Aswan Low dam’s reservoir.

They were among the last visitors to see the complex in its original site and condition. In 1902 the temples were submerged under water when the dam’s sluices were open from November to June encrusting the structures with silt and causing damage.

Abu Simbel & Philae

The twelve photographs of the Abu Simbel temples from 1901 are of historical significance for these monuments would be relocated in the 1960s. This was done to prevent submersion following the construction of the Aswan High Dam which opened in 1970. The monuments enjoyed by Charles and Ellen are today recognised as World Heritage Sites known as the Nubian Monuments. The Sussex Egyptological Society expressed much interest in seeing photographs of these monuments in their original locations.

“The second photo album was a sheer delight” the society newsletters runs, “at Cairo were the Giza pyramids with the Sphinx emerging from the sand. At Luxor there were recognisable photos of Medinet Habu, the Ramesseum, Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple, the Colossi of Memnon, Luxor and Karnak temples. It was thrilling to see how these sacred sites looked well over a hundred years ago, just as those adventurous Edwardians saw them…”

A momentous happening

Charles and Ellen Thomas-Stanford’s trip to Egypt coincided with an event of historic significance: the death of Queen Victoria on 22 January 1901. Most people alive in Britain knew no other monarch. You would have to be well over 70 to remember a time before the Queen came to the throne. As life expectancy in Britain was around 50 in 1900 that meant a small percentage of the population (in 1901 only 8.1% of people in Britain were aged over 60). Aged 52 on her Egyptian holiday, Ellen Thomas-Stanford was born eleven years into Victoria’s reign.

The news must have come as a shock, not least because Ellen was close friends with the Queen’s youngest daughter, Princess Beatrice. Victoria was elderly but her final illness had been very short, catching even her household by surprise. Perhaps unsurprisingly the Queen’s subjects were equally startled. Momentous world events stick in the mind as does one’s location on hearing the news. Is it possible, I wondered to work out the Thomas-Stanford’s location at the death of their monarch?

The first photographs in the albums put the Thomas-Stanfords in Cairo on 5 January.

Frustratingly few of the photographs are dated but those that are show the couple were in Thebes and Luxor on 15 and 16 January, Abu Simbel on 31 January and at the Temple of Derr in Lower Nubia on 2 February, the day Queen Victoria’s funeral took place at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle. I calculate the Thomas-Stanford party were on the Aswan Dam stage of their Nile journey on the date of the Queen’s death.

The Victorian internet

Queen Victoria was the first British monarch whose death was reported at speed around the world by means of telegraph, a communication system so significant it has been called the Victorian internet. Messages were sent along telegraph wires and cables which by 1900 had been laid under sea and above land connecting the globe. A letter from London took two weeks to reach Egypt. A telegraph message could be sent in minutes.

Cairo was connected by the Eastern Telegraph Company (founded in 1872) and looking at the Thomas-Stanford’s photographs there are telegraph poles and wires to be seen in some of the shots, even though the photographer studiously avoids the modern.

Telegraph pole and wires at the Kasr El Nil Bridge Cairo January 1901

Also connected 400 miles to the south was Luxor, in 1901 a bustling city marketed as a health resort to wealthy visitors. Luxor in winter contained an eclectic mix of archaeologists and aristocrats, all of whom would have been talking of the Queen’s death. Aswan is 112 miles down river from Luxor where the news must have quickly spread even if by word of mouth, January being the busiest month of the tourist season.

Home to a changed country

The Thomas-Stanfords returned to their London home at 3 Ennismore Gardens Knightsbridge. This was their main residence prior to their 1905 move to Preston Manor. We know they were back in Britain by 31 March 1901 because they appear on the census taken on that date.

Ellen and Charles would have looked forward to seeing their photographs developed and then spent happy hours fixing them into the three albums now kept at Preston Manor. Did they reminisce, opening the albums over the years on leaving Britain as Victorians and returning Edwardians?

Paula Wrightson, Venue Officer Preston Manor