The story behind the picture: A Jack Johnson Exploded Near Him

This is a legacy story from an earlier version of our website. It may contain some formatting issues and broken links.

A highpoint of my time working as the Adult Learning Officer for Royal Pavilion & Museums Adult Event Programme came in 2014 when the centenary of the start of the First World War bought an opportunity to open the archives and uncover the story of how the people of Brighton faced a time of unprecedented international crisis.

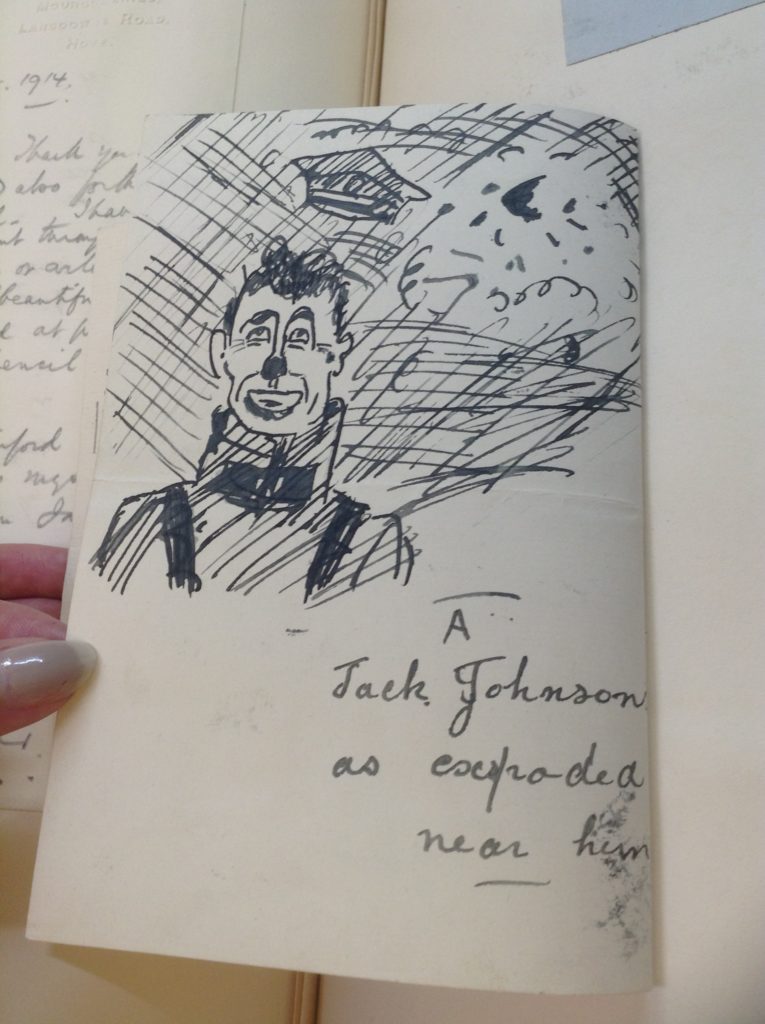

This picture shows a page from a letter written by Private R. Yates and illustrated by cartoons sent to Ellen Thomas-Stanford of Preston Manor on 10 November 1914.

The letter caught my attention because the cartoon made me smile and had me wondering. What’s a Jack Johnson?

Private Yates was a superb cartoonist. Here he sketches himself at the moment of explosion, his cap blown clear off his head. I love his expression of surprise and the way he has captured the sheer force, noise and mayhem of war with a few strokes of his pen.

A thank you letter from hospital

Private Yates wrote the letter from his bed at the Royal Navy Hospital Plymouth where he was being treated for wounds. He thanked Ellen Thomas-Stanford for the gifts she sent to him and the other wounded men. He did not know her personally. Mrs Thomas-Stanford was an unknown but much-appreciated lady benefactor doing her bit for the war effort by making charitable donations of cigarettes and chocolates.

Ellen Thomas-Stanford was 66 years old when war broke out and like many wealthy women, she sought ways she could put her resources to use and help those caught up in war. Britain in 1914 had no National Health Service. In effect, health-care was private. You paid for medical treatment and if you couldn’t pay, you sought help through charities. The nation’s health-care provision was therefore stretched both medically and financially by the constant flow of tens of thousands of men returning wounded from the battlefield.

During the 1914-18 war Ellen and her friends stepped-up their work raising funds for medical charities. Huge sums were raised for The Red Cross and the many military hospitals that sprung up all along Britain’s south coast, some in private homes given over to the wounded. Grand ladies preferred their seaside homes to be used as convalescent hospitals for officers. Lower ranked men like Private Yates would find themselves in more basic surroundings.

A battle story

The Royal Naval Hospital, Plymouth was 150 years old by the time Private Yates was admitted. Treatment would have been the best possible in this old naval hospital but comforts like cigarettes and chocolate were rare luxuries. We can’t know if Private Yates wrote of his own accord or if the wounded men were instructed by their superiors to send letters of thanks. I picture this battle-worn soldier sitting in bed scratching his head wondering what on earth he can write to a well-heeled dignitary in Brighton after he’d expressed his thanks for her gifts.

He describes his path from war to hospital, a vivid account in few words

‘we were at Ypres trying to capture a machine gun which some snipers had in a farmhouse, which they were very fond of hiding in. We were beating back as the enemy were too strong for us’

Then a Jack Johnson exploded

A boxing champ

I guessed a Jack Johnson was military slang and looked for its origin, which I soon discovered. Jack Johnson was a famous American boxer who became the first African-American world heavyweight boxing champion (1908-1915). Johnson was front page news all over the world for his skills in the boxing ring and for the incidents in his private life that came with fame, money and tensions around race in the US at that time. The sporting pages of newspapers, read avidly by soldiers on the Front, were filled with tales of Jack Johnson whose name was on everyone’s lips. British troops in the trenches borrowed his famous name to describe the powerful black-coloured German 150mm heavy artillery shells that exploded with devastating force.

Private Yates ends his short letter by writing ‘I think this is it at present, from Yours Truly, Pte, R. Yates’

And so, that letter from 1914 with its cartoons and message of thanks lay hidden for a century. Reading its message afresh in 2014 I knew I was looking at something extraordinarily special. Here was one man’s brush with death encapsulated in brief words and swiftly-penned drawings folded into a tiny blue envelope stamped ‘Passed by Censor’ and delivered into history.

At the peak of war 12 million letters and parcels a week were sent from Britain to men fighting overseas. Millions of letters also circulated on the home-front, as disposable as today’s electronic digital communications.

Ellen must have cherished this particular letter because she selected it from the thousands of letters from friends, family and person’s unknown to her, that she received in the 1914-1918 period and had preserved in five large leather-bound volumes now kept at Preston Manor.

Paula Wrightson, Venue Officer Preston Manor