Decolonising Father Christmas

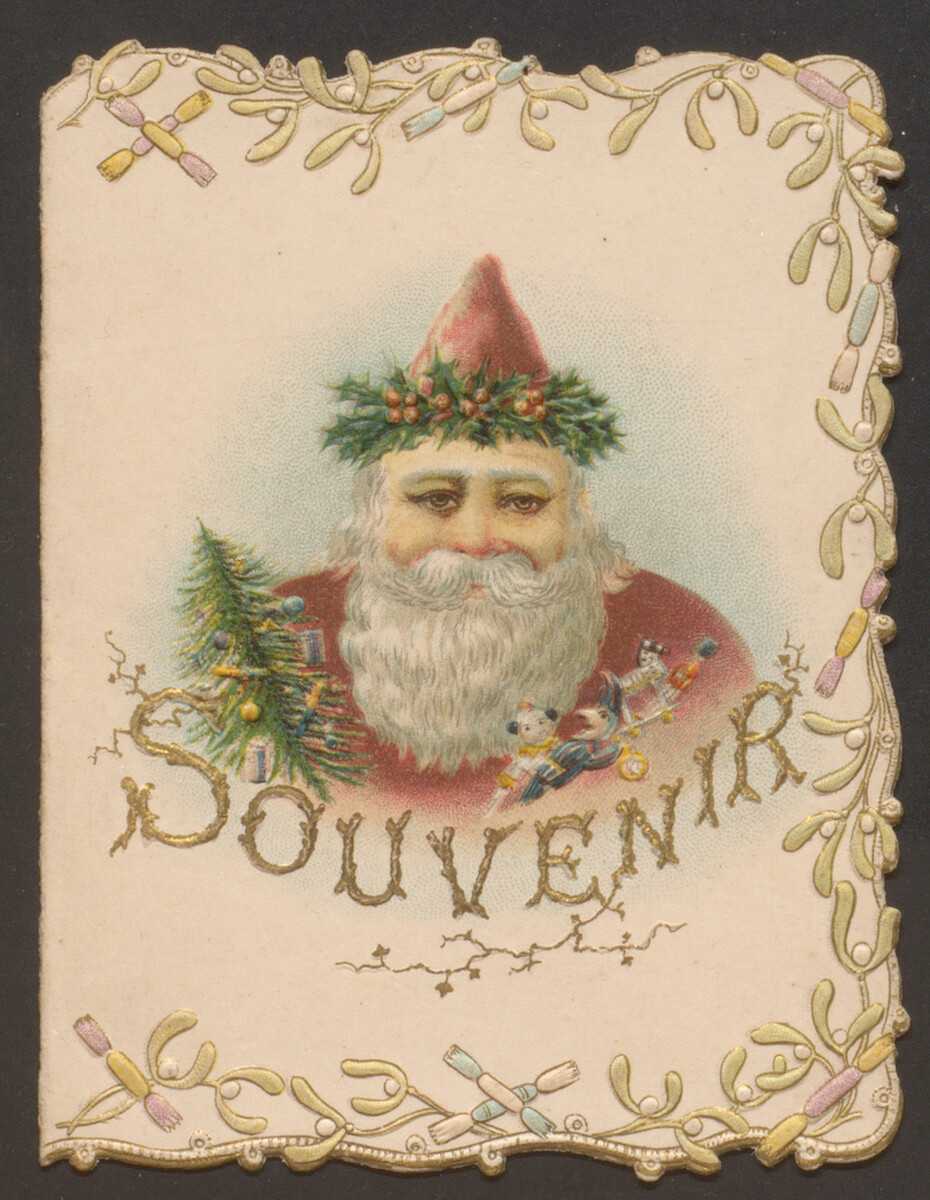

For many children, the story of Santa Claus is as much a part of Christmas as gifts and Christmas dinner. But the tale of a white, Western Santa who judges all children’s behaviour has problems.

Our Culture Change project is about telling more stories of all of us who helped make history, and also challenging accepted narratives. As with all history, we re-evaluate events, re-examine why things happened, who was involved and we re-interpret.

With Christmas rapidly approaching, and Brighton Museum & Art Gallery now hosting Father Christmas in his grotto, it seemed a good time to share my thoughts – some old and some new – about the message that the story of Father Christmas sends, and how we can update the tale for modern audiences.

In the popular myth in many Western cultures, Santa flies his sleigh around the world on Christmas Eve. As he visits each nation he determines if the children deserve presents based on being ‘naughty’ or ‘nice.’ But who decided Santa should be the judge of children’s behaviour in every community? How can he assess, for example, Indigenous children practicing their own cultural traditions?

Told like this, the story presents Santa as the ultimate authority of all societies. This asks us to accept colonial assumptions of cultural superiority. It doesn’t recognise the complex realities colonised people face.

And it can erase Indigenous cultural practices and sovereignty. For example, in many Santa storybooks of my youth, and later when exploring the story with children in the family, other cultures appeared simply as backdrops for Santa’s adventure. There might be a flag, and illustrations of children in their national costume, but we learned nothing about those places and people.

This perpetuates the harmful ‘colonial gaze’. Non-Western cultures are ‘othered’. It says that the coloniser has the power to judge all people. And it ignores many communities’ histories and traditions. Telling the story like this teaches new generations that the coloniser knows best.

And what do we say by having an old white man supervise the elves’ work? Is it something entirely innocent – elves are magical, mythical beings completely separate from the real world – or is there more to it? Are they representative of other groups? How do they reinforce how marginalised groups view not only ‘father figures’ but also themselves?

Mythical maybe, but elves are identifiably different to what is often presented as ‘normal’, which is white, male and non-disabled. And in the stories, the ‘different’ ones make the toys and the white, non-disabled man supervises them.

We can tell the story of Santa in a way that starts to challenge the colonial gaze. Here are some ideas:

- Portray Santa as one of many winter gift-givers around the world. Highlight diverse winter traditions and spirits/figures specific to each culture.

- Have Santa learn about different cultures rather than judge them. Stories could show him experiencing their traditions. Emphasise cultural exchange rather than assessment.

- Have communities teach Santa about their practices and histories.

- Talk about where different parts of the Santa myth came from. For example, how we absorbed the Sami peoples’ traditional reindeer herding into the story. For young children, where we don’t yet want to expose that it is a myth, give credit to the Sami people as having taught Santa about reindeers and how to look after them.

- Remove Santa rewarding children based on a Western binary of ‘naughty/nice.’ Focus on bringing joy to kids of all backgrounds rather than judging them.

- Include people from around the world in Santa’s workshop. This acknowledges global input.

- Put Santa to work in the factory alongside the elves. This shows him and the elves as equal.

- Tell stories that don’t place the origins of gift-giving with Santa. Point out that many cultures have had their own winter gift traditions for a long time.

- Teach about local historical winter traditions. Incorporate them into celebrations.

- Have Santa be a more diverse character who celebrates cultural exchange. Avoid promoting one culture’s dominance. An inclusive adaptation could include many Santas from different regions.

- Include some Mother Christmases. Patriarchy and colonialism went hand in hand. Show the next generation that men don’t have to be in charge.

The goal is moving away from a colonial narrative of dominance. Instead, tell a story that emphasises cultural diversity, exchange and respect.