Passion, Power & Protest

Explore more of the stories behind our objects in the Passion, Power, Protest Gallery with this specially created content.

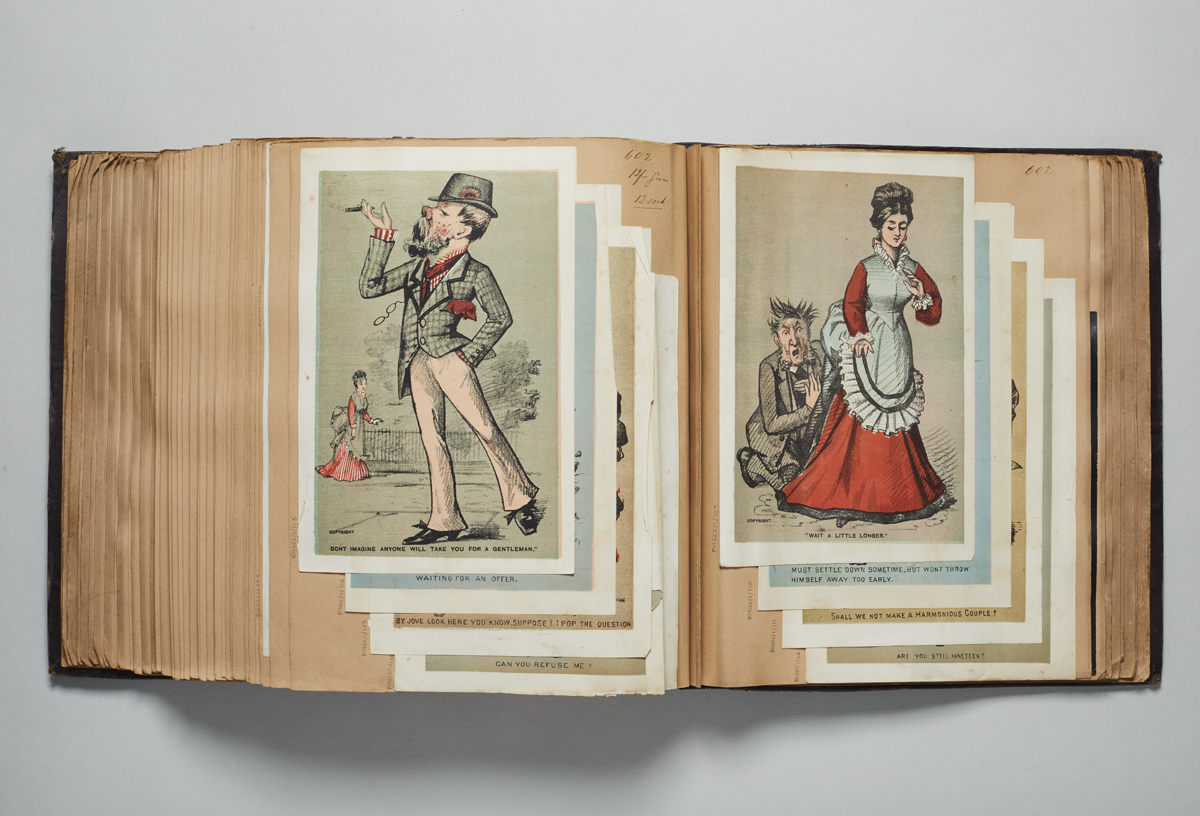

Victorian Card Album

Read more about our Victorian Valentines cards in our post Love Letters and Hate Mail: Victorian Vinegar Valentines

The Kiss in the Tunnel film directed by George Albert Smith

To read more about The Kiss in the Tunnel film directed by George Albert Smith visit Screen Archive South East

Dress designed by Alexander McQueen

U-Bya (headdress) and outfit from Kentung, Burma / Myanmar

Traditionally, this distinctive outfit and accompanying u-bya (headdress) would have been worn by a married Lomi Akha woman. The Akha are a cultural group from eastern Burma/Myanmar and across southeast Asia, having migrated over many years. There are large populations living in northern Thailand and the Yunnan province in China.

This particular outfit was purchased during field collections in Burma/Myanmar in 1996. They were purchased in Sungsak village near the town of Kentung from a shop belonging to Daw Khin Htway (Akha name: Bu Yae), a Roman Catholic Akha woman residing in Kengtung, who deals in old and new Akha textiles and jewellery.

The basic outfit of an Akha woman consists of a headdress, jacket, halter, skirt, sash and leggings. The style and decoration of an Akha woman’s clothes and headwear vary according to which cultural subgroup they belong to. The flat, trapezoid back plate to the headdress and the appliqued rows of contrasting diamonds and triangles in this outfit indicate it belonged to the Lomi Akha group.

The headdress represents a woman’s social and marital status. Girls wear a cloth cap which is swapped for a headdress during adolescence. The girls then adorn these headdresses with beads, feathers, seeds and tassels until they reach an age of maturity and readiness for marriage at which point silver coins and balls are added. Once married, the distinctive flat trapezoid embossed back plate is added.

Textiles are made on looms, primarily by women. Traditionally, cotton was grown and processed into cotton, with girls learning how to spin the cotton from an early age. The distinctive dark blue indigo colour that is predominant across the textiles comes from a native plant known as myang. The deep colour is achieved through a process of constant dipping and drying over the course of a month.

These incredible textiles are more than just clothes: they are an expression of cultural heritage, of identity and of artistic skill. They are the backbone of society and social relationships and are a way of passing down stories.

The textiles have huge personal and emotional significance for Akha women. They make them themselves, working on and adding to them over long periods of time. Traditionally these outfits including the headdress were worn at all times, in the fields and even to sleep! The quality of the textiles and adornments influenced a man’s choice of partner; the skill of the needlework was an indication of her personality, and lots of silver indicated wealth. These skills were honed throughout childhood and adolescence. The full outfit is a culmination of this growth into womanhood.

Object information

- Textiles

- 1996

- Metal, cotton, plastic, shells, seeds

- WA507480, WA507483, WA507485, WA507486, WA507487, WA507488.1-2

![wap0083, Kaw [Akha] girls dancing to man and pipe. Burma image, credit James Henry Green Charitable Trust](https://brightonmuseums.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/wap0083-Burma-image-credit-James-Henry-Green-Charitable-Trust-1200.jpg)

WAP0083. Kaw [Akha] girls dancing to man and pipe (Researcher’s notes in brackets)

“The Akha men are certainly not a light hearted race; they dance occasionally to the music of the ‘ken’, but the men’s dances are far from joyous. Four or five of them gather together in a small circle, with their heads facing inwards, and shuffle round and round in a sort of figure. The women have to dance with some caution on account of the elusiveness of their skirts, but they occasionally show off, and when they are particularly cheerful they break out into what can hardly be called dance, but is rather violent exercise. Two women face one another, with their feet together, and clasping hands they lean back as far as they can go and go whisking round in a circle with great energy.” [‘Burma and Beyond’, Sir J. G. Scott, London, 1932, p.275]

![WA1516. Kaw [Akha] women weaving. Burma image, credit James Henry Green Charitable Trust](https://brightonmuseums.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/wa1516-Burma-image-credit-James-Henry-Green-Charitable-Trust-1200.jpg)

WA1516. Kaw [Akha] women weaving. (Researcher’s notes in brackets)

“The head-dress of these [Akha] women is most characteristic, and with most of the clans very striking. The simplest form is that of two circles of split bamboo, one going horizontally around the head and the other fastened on to it with a sort of hinge, so as to slope over the back of the head. These circlets are covered with dark blue cloth, decked out with whorls and bosses and spangles of silver and hung with bands and festoons of coins and small dried gourds. An elaboration of this head dress has a peculiar erection of bamboo like a bishop’s mitre in the middle. This is also decorated with the coins and small gourds and seeds and shells.” [‘Burma and Beyond’, Sir J. G. Scott, London, 1932, pp.269-270]

by Portia Tremlett

Mae West Lips Sofa by Salvidor Dalí and Edward James

Mae West Lips Sofa by Salvidor Dalí and Edward James

In 1935 Salvador Dalí met the British collector and poet Edward James, who became his friend and patron. In 1936 Dalí stayed with James at his London home, where they developed several ideas for Surrealist objects and furniture. James suggested they should create a sofa based on Dalí’s painting, Mae West’s Face which May be Used as a Surrealist Apartment (1934 – 35). Dalí believed that the female form, particularly as represented by West, embodied the model of ultimate feminine beauty. The sofa is a symbol of his obsession and fetishisation of Mae West within his work.

West was one of the biggest box office draws of the 1930s and was also the highest paid woman in the film industry of the time. Her popular performances were controversial in the conservative prohibition era. West wrote and directed the majority of her own scripts but she was often subjected to censorship. Two of her plays were censored in her lifetime. Sex landed her in jail for 10 days for “corrupting the morals of youth”; The Drag, a play about homosexuality, never opened on Broadway after the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice campaigned against it.

West used her feminine figure, beguiling character and witty comments to her advantage and was very forward thinking for her time. She became one of the most famous film stars of the century and continues to influence people today.

Further details

“A surreal Legacy: selected works from the Edward James Foundation”, essay by Dr Sharon Michi-Kusunoki, Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) and Edward James (1907-1984), Mae West Lips Sofa | Christie’s

Object information

- Salvador Dali, Edward James and Green & Abbott

- c1938

- Felt and wood

- DA300594

- Purchased by Brighton Museum & Art Gallery from the Edward James Foundation in 1983 with the support of Charles Robertson and the V&A Purchase Grant Fund

by Nicola Coleby and Joanne Smith

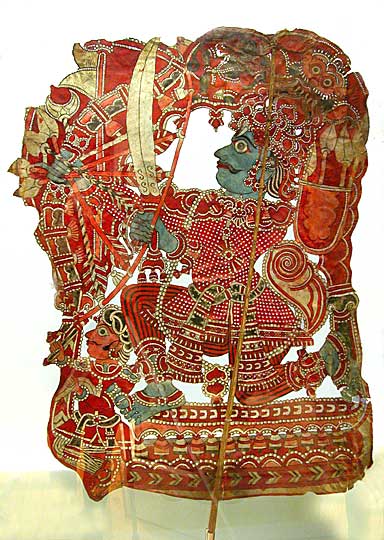

“Sita” Tholu Bommalata (shadow puppet) from Andhra Pradesh, India

Tholu Bommalata (Shadow Puppet Theatre), Andhra Pradesh, India

Tholu Bommalata is a traditional Indian shadow theatre performed with handmade leather puppets. The main language in Andhra Pradesh is Telugu and, literally translated, ‘tholu’ means ‘leather’, ‘bommalu’ means ‘puppets’ and ‘aata’ from ‘attam’ means ‘dance’. This form of theatre dates to the third century BCE and is performed by travelling troupes of entertainers who go from village to village. The shadow theatre is often accompanied by music, songs, dances and would be part of a whole night’s entertainment.

Sita is a female figure with ornate clothing and accessories, an elaborate headdress and jewellery, and a long plait which is articulated along with the arms. Sticks are attached to the body and arms to control the puppet’s movements. The pleated robes of the figure’s skirt are decorated with a red-and-black check pattern. The body is a pale ochre colour, dyed with ink and highly decorated. Perforations are used to highlight details of the costume and accessories.

There are three Tholu Bommalu in our collections which depict Rama, Sita and Hanuman. These puppets would have been used to tell the story of Ramayana, a Hindu epic in which love, loyalty and duty intertwine to play complex roles. The story of Rama and Sita varies by local traditions and is considered one of the two most important epics of Hinduism. Some Hindus consider the Ramayana a sacred text and Rama, Sita and Hanuman, to be the gods themselves, while others see the characters as an avatar – a representation of the gods in one of their human forms.

The Upanishads, or Hindu texts, describe Sita as having powers of desire, action, knowledge and strength. They describe Rama as having the power of divine truth, bravery, compassion and devotion. Hanuman is known for wisdom, selfless devotion, strength and courage.

The story centres around the abduction of Sita, and Rama’s epic journey (Ramayana) to be reunited with her. The epic explores the importance of ‘dharma’ (righteous duty), courage and steadfastness, and different types of love, such as the love between parents and their children, the love between spouses, and brotherly love. In some versions, Sita is abducted because of her desirability. Once she is rescued she has to demonstrate her chastity through a fire test. In other versions, Sita remains hidden in the fire and only an illusion of her is abducted, testifying to Rama’s character.

Ultimately, the poem teaches balance – that passion must align with ‘dharma’ to lead to good outcomes. It is a timeless story with hidden meanings that are still relevant today.

Object information

- late 19th century

- Leather, ink

- WA507532, WA507528, WA507526

- Purchased with the aid of the MGC/V&A Purchase Grant Fund, 1992

by Joanne Smith

Angel by Alison Lapper

Alison Lapper MBE is an artist, presenter and disability arts patron. She was born with no arms and shortened legs and spent the first 17 years of her life at Chailey Heritage School in Sussex. Alison Lapper uses her work to challenge perceptions of norms and societal ideas. She shows us what can be achieved when we conquer our own circumstances and live life to the full.

Excerpts from an interview transcript with Alison Lapper MBE for ‘See Portraits, Be Portraits’ exhibition at Brighton Museum (9 October – 28 July 2019).

Alison … I’m not talking of your exhibition in particular now, but diversity, I think like we don’t really see a lot of; like me. In yours [exhibition] you’ve addressed that cos I’m in it but on the whole like me I’ve never been to an exhibition that looks at diversity, except maybe Mark Quinn that addresses diversity in quite the same way. To me, mine [my portrait] doesn’t even fit in there, I look at it as the sort of ‘u-ah’ in the room.

… it’s so unusual… to go to a gallery where you can actually interact with what’s hanging on the walls I don’t think I’ve ever really seen that… And again, it’s normally it aimed exclusively at children and not at adults and I love the fact that you can go in there and kind of have free range, that’s so unusual and everywhere should do it. You’d get far more involved in the art work and look at it more cos you’re having opportunity to interact with it.

… where do you go to a gallery where there’s a bit of fun? I think it gets you more involved added into the mix again I don’t think that happens enough, were all very serious, aren’t we, about art and I think that’s why a lot of the stuff I do is tongue in cheek because we don’t have to be so serious

Curator How should do you think we use the work of living artists in our collections to develop new audiences?

Alison Ummm, We’re here and alive and as you say people can come and listen to us, talk to us, does that bring the next generation on because I can interact with that artist, it’s not 500 years on and that person maybe doesn’t feel relevant to a younger audience or any audience, whereas hopefully if you’re living breathing, people can meet you talk to you ask you questions, I think that’s a really good way of getting people interested.

Curator As an artists working nationally and internationally are there any innovations in galleries you’ve seen that would enhance BMAG’s audience experience?

Alison Oh my goodness, Off the top of my head no, again I don’t think , I could be wrong, but you never really see art displayed very differently from museum to gallery to museum, it’s always the same. I did a series of work where I actually put my work on the floor you could walk on it. The only other person I’ve seen do that and I can’t remember the artists named but again it’s not usual to see on work like sculptures “Don’t touch” if you’re blind I understand they’ll let you put gloves on but why can’t we do that, people that can see why can’t they put gloves on and I know there’s a big argument of preservation and what have you.

… I think that’s a shame as well there’s so much [museum collections] that isn’t on display, so much. So we need glass floors so we can see it’s there. I don’t know why they do so much written [interpretation], I’m dyslexic so all that written stuff is just a jumble so I just go [to galleries] for what I can see and the experience and I don’t think we make art an experience. Why do we only put art on the walls or on plinths, we don’t really do much else with it. I don’t think we make art an experience even me 16 feet tall on a plinth is not accessible particularly is it? You need to make it more accessible – have fun with it really.

… I think that mine [my portrait] almost doesn’t fit in [traditional exhibitions] but I like the fact that it doesn’t fit because it looks too modern to different and again the subject matter, disability, it kind of ticks all the boxes.

Artwork details

- Alison Lapper

- Angel

- 1999

- Digital print on canvas

- FA208038

Edited by Joanne Smith

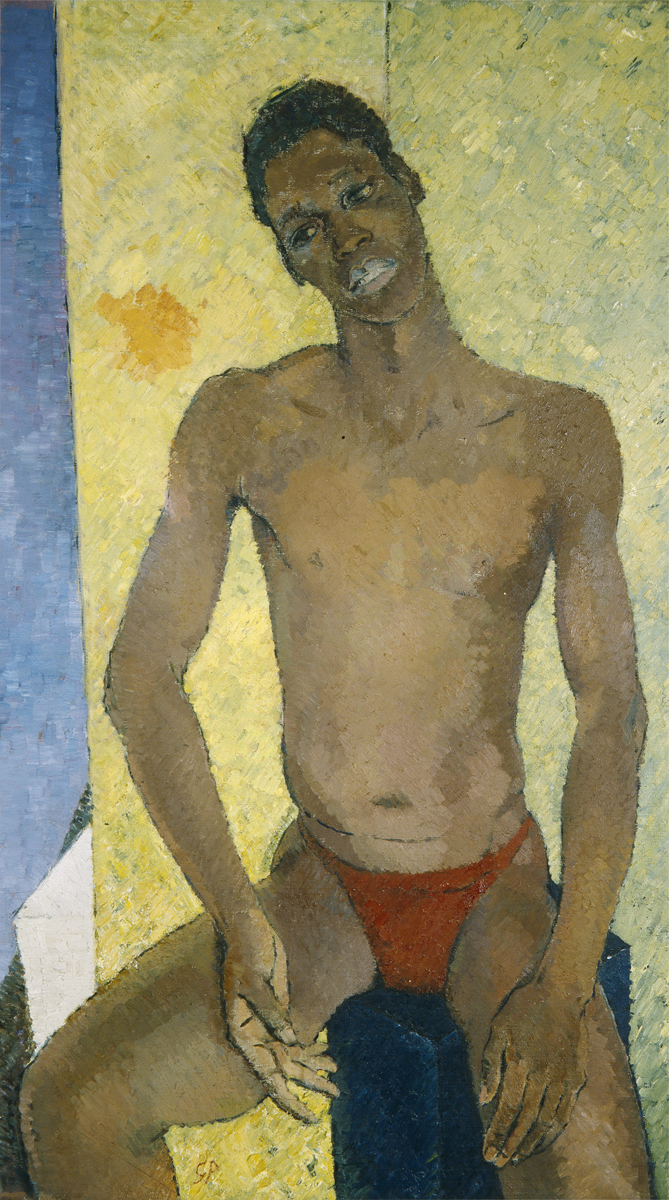

Melancholy Man by Glyn Philpot

Hidden Passions: Faith, Desire and the Quiet Power of Melancholy Man by Glyn Philpot

Henry Thomas leans forward slightly, his head tilted and eyes distant. There is a tension in his face, a flicker of weariness. The expression and pose are open, his near-nude body equally unguarded. Thomas is exposed, both physically and emotionally, through the painter’s gaze. Such openness was rare in 1930s portraiture and speaks to the familiarity between artist and sitter. The effect is quietly unsettling, as if we have stumbled upon a private moment. Painted in 1936, the intimacy of Melancholy Man makes the viewer feel almost intrusive.

Glyn Philpot was a celebrated society portraitist and a devout Catholic. It is likely that he was also gay, working at a time when homosexuality could not be publicly acknowledged. However, his relationship with painter and poet Vivian Forbes from 1923 until 1937 was an open secret among their circle. That balance between visibility and concealment shaped both his life and art.

The tensions between Philpot’s faith and sexuality are apparent in Melancholy Man, The golden yellow background behind Thomas recalls the icons of Catholic devotion while Thomas’s physicality conveys personal desire. By the 1930s Philpot’s style had become more experimental and introspective, replacing conventional realism with a devotional intensity. As he shifted towards modernism and a growing preoccupation with the male form, his society commissions began to diminish.

Philpot met Thomas, a Jamaican man, in 1929, introduced to him by his godson Oliver Messel, a theatre and costume designer. Messel first met Thomas at London’s National Gallery when he arrived in England after working as a stevedore on a Jamaican ship. Thomas worked for Philpot as servant and model, appearing in several paintings where he was cast as a king, saint and allegorical figure. These earlier works elevate Thomas to the realm of myth, reflecting both admiration and idealisation. In Melancholy Man, painted near the end of Philpot’s life, that grandeur falls away. Thomas appears instead as a private presence, observed with emotional candour. Yet the power to look and to reveal remains Philpot’s alone, and the portrait’s intimacy leaves the viewer aware of a delicate, unequal exchange.

Here, passion is not the drama of romance but the quiet intensity of Philpot’s gaze. Power lies in that act of looking, in the artist’s comparative social standing and his authority to reveal. Yet within that imbalance lies a quiet protest. In portraying a Black man with such emotional presence, Philpot departed from the conventions of his age. Melancholy Man asks us to see Thomas as he did, but also to question what it means for one man to be seen through another’s longing.

Further details

Henry Thomas: Muse to Glyn Philpot | Perspectives

Glyn Philpot: portraiture and desire | Art UK

Artwork details

- Glyn Philpot

- Melancholy Man

- 1936

- Oil paint on canvas

- FA000132

by Zoe Suggars

Figures by the Sea by Wilfred Avery

Wilfred Avery is a British artist and a figure praised for his artworks which relate to nature and the human body. As a queer artist, Avery’s acceptance of his sexuality played a part in the subject matter of his later paintings, including Figures by the Sea.

Focussing largely on landscapes and the male body, Avery engages with the modernist genre. Modernism is a broad artistic movement, one which began in the late-nineteenth century. It reflected modern, industrial life by being far more visually experimental than artwork had been previously. The large, blue, swirling shapes that Avery utilises in Figures by the Sea abstract the image. The figures that are represented are largely symbolic and fragmented and therefore makes it an example of the modernist genre. During his studies, Avery met the surrealist artist Paul Nash who recommended he look at Parisian influence for his work – Paris was a central hub for modernist art.

The abstract shapes make the bodies look at one with the water. This work, as is a central theme in many of Avery’s paintings, centres the homoerotic. Some of the abstracted shapes that make up the muscular bodies are noticeably phallic, whilst the viewer is placed into a voyeuristic position – looking into a moment of intimacy. The blue tones are reminiscent of his earlier series of paintings Sixties Figures, where the during the 1960s, the artist experimented with the subconscious and compositions of entwining male bodies. Many of these works are compositionally similar to this piece. His artistic method for these works involved painting with no outline, so the composition could flow experimentally and organically. Using this subconscious method of production, the artworks are fluid and tie in with themes associated to other artistic movements – like surrealism.

Figures by the Sea was an image composed by Avery after his move to Sussex in 1995 with his life partner, Ray Crossley. This artwork was painted in Kemptown and as a result has a distinct, local connection. Avery’s relationship gave him comfortability painting homoerotic subject matter, at a time where this was seen as controversial. This links the artwork to this gallery’s core themes, passion and protest.

Overall, this work can be seen as using the modernist genre as a tool to depict queer identity. Avery, through the subject matter of nude male figures, creates a sense of resistance to social oppression.

Artwork details

- Wilfred Avery

- Figures by the Sea

- 1996-7

- Oil Painting

- FA001274

- Presented by the executor of the Estate of Wilfred Avery with Art Fund support, 2022

By Katie Mahoney-Roberts

Iriabo Woman by Sokari Douglas Camp

Sokari Douglas Camp CBE is an artist who specialises in welding, cutting and shaping sheet steel into dynamic sculptures. She is from Buguma, the principal settlement of the Kalabari people, in the Eastern Niger Delta. She is based in London and takes inspiration from her Kalabari heritage, Nigerian culture and life in the UK. She uses her pieces as a social commentary to spark conversations and inspire social change.

Excerpts from an interview transcript with Sokari Douglas Camp about her sculpture ‘Iriabo Woman’. The artist sometimes refers to it as ‘Iriabo Woman in her Prime’.

Curator What inspired you to make this piece?

Sokari I made this piece after my brothers became chiefs, I was very impressed by my nieces who looked very grown up and beautiful during the ceremonies.

‘Iriabo’ means prized woman, a woman regarded as an asset to her family. Iria is a state that women are generally put into when they have had children. Iriabo also means an Iria participant. The women are fed so that they gain weight for a few months, if their family can afford this, then they are paraded around the town in different styles of lriabo dress. This has always been a very full skirt made of layers of cloth with folds like a Ra-Ra skirt. It has to be at a certain height above the knee so that the woman can wear beads at the top of her calf. The top of an Iriabo outfit varies, the woman can be topless or wear a silk scarf or a lacey blouse. This can be according to the fashion at the time or the individual’s taste. Young Iriabos can go topless; an Iriabo can be as young as three.

The sculpture Iriabo is also an example of my tackling wood and steel at the same time. I love both materials and I love the challenge of trying to make them work together. The open spaces that the steel creates is a challenge; one fills it in with a chest in the case of the Iriabo sculpture, but it is empty space. The wooden skirt reminds me of the layers of cloth worn by the Iriabo; the skirts do make one feel as if one is rolling in a band of cloth and the dancing that is done in this state is gentle and the dancers look as if they are bobbing around because the skirt is so much wider than the dancers’ actual figure.

The music played for the Iriabo is on pot drums that have a very soft echo a bit like blowing in a bottle with water in it, except it is a clay drum with water in it played by hitting the lip of the drum with a raffia fan.

Curator Can you tell us more about the Iria ceremony?

Sokari [Iria is] a five-week coming of age ceremony which transforms Okrikan and Waikiriki girls of the Niger Delta into marriageable women.

The purpose of Iria is to certify a woman’s chastity and marriageability. Iriabos whose families can afford the cost, have their bodies decorated with Burumo painting ‘a sacred, ephemeral art’. The candidates are then taken in a procession to the market square, where they must parade their bodies to a large public gathering of chiefs and villagers. Here their breasts and bellies are examined by an older woman to confirm that they are not pregnant. After the Iriabos pass this test, designed to publicly validate their virginity, their mothers pay the chiefs 20 naira, in a process known as ‘ticketing’, for the privilege of undertaking the rite. Blacksmiths then install heavy brass ring impalas around their legs and the Iriabos begin a phase of seclusion. With movement limited by these clanking leggings, the women spend the next three weeks in ‘fattening rooms’ where they are continuously fed and pampered…. The weeks that they spend in confinement is the time when the Egelreme teaches them about men and motherhood…

Following this confinement period, they are wrapped in skirts of abundant fabric which accentuate the midriff. This serves as a sign of both family wealth and the girl’s incipient fertility. Fitted in these special skirts, they are then publicly enthroned in ‘viewing booths’ decorated with family photographs. On the last day of the Iria there is a race: the Iriabos are chased by boys and young men led by a male performer in the role of Osokolo, a warlike spirit from the land of the Ijaw, who hits the girls with a stick to separate them from their water-spirit lovers. The Iriabos are now considered women, ready to marry human men and bear children.

Curator Can you tell us more about the roles of different people involved in the ceremony, men and women?

Sokari … Though strongly exclusive of women at the present day, the society acknowledges a female deity, Ekineba, as its founder and patroness; a woman Akweke as the first human being to have seen masquerades (she saw them danced on a mud flat by the Water people); and an enigmatic Ekine Erebo (‘Ekine woman’) as the spiritual power behind certain individual masquerades.

… while senior males apparently seek to shore up their privilege to discipline and control the legitimate fertility of women, the latter treat Iria as an arena in which to negotiate their own identities.

Curator How would your art be perceived in Nigeria?

Sokari In my own situation in Nigeria, I would not be given the opportunity to make art, because objects in my part of Nigeria are religious. If I were making objects in Nigeria, I would be a priestess…

Object information

- Sculpture

- 1995

- Steel, wood, glass

- WA508616

Edited by Joanne Smith and Portia Tremlett

Neck irons

How can we honour the stories of those enslaved?

Neck irons

The original museum catalogue entry for this object reads, ‘Slaves Neck Iron, English or American made’. We have no other information about these shackles, other than they were donated by Henry Willett, one of the founders of Brighton Museum.

These are difficult stories to be told, when much of this history has been purposefully erased. We are working with the community to help us tell this story in the most appropriate way.

Object information

- Neck irons

- unknown

- Iron

- AF72

Teapot with Kabuki actor

Power and Porcelain: Reframing a Victorian Teapot

This teapot, modelled as a seated Japanese Kabuki actor holding a mask, was produced by Minton(s) Pottery in Stoke-on-Trent in 1888. Decorated in vivid majolica glazes, it showcases the remarkable technical skill in glaze-making for which Minton(s) was renowned. Catalogued as Pattern No. 1888, the teapot was created for export to European markets, appealing to consumers eager to display their fascination with cultures beyond their own.

Today, it is a highly collectable object, with very few examples known to survive. One other similar example in held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from 1874.

Yet beneath its charm lies a more complex story. Rather than offering an authentic reflection of Japanese culture, the design reveals a European interpretation of East and South-East Asian aesthetics—filtered through imitation rather than genuine cultural understanding.

Minton(s) was one of the most influential ceramics manufacturers of the Victorian era. Founded in 1793 by Thomas Minton, the company first specialised in transferware pottery before expanding under the leadership of his son, Herbert Minton, in the 1830s. By the time Colin Minton Campbell took over from his Uncle in 1858, Minton’s had become synonymous with the Aesthetic Movement, producing ornate ceramics inspired by an eclectic mix of global decorative traditions.

This fascination with the “exotic” that forms part of the Aesthetic Movement, was also part of a broader cultural phenomena known as Orientalism, the Western idealisation and misrepresentation of Asian and Global South cultures. Objects like this teapot were admired for their foreign beauty, but they also reinforced stereotypes, presenting non-European cultures as decorative curiosities. Orientalism in practice only allowed global cultures to be seen through a colonial lens and items typically made by European manufacturers, like Minton(s) for their home-grown audiences.

Museums, including Brighton & Hove, have also historically played a role in shaping and perpetuating these orientalist narratives. Earlier collection records for this object, for example, include racist-inflicted terms. With previous curators describing the spout as “grotesque mask” and overall figure as a “Chinaman.” A complete misrepresentation of the culture and history from which the teapot is drawn. With such language reflecting the biases of the time, rather than the artistry or cultural identity that inspired the piece and the rich history of Kabuki theatre from which the design has been inspired.

By re-examining and re-describing objects like this today, we can confront those legacies and begin to tell more truthful, inclusive stories about the global histories that shape museum collections. Through this process, we move beyond a Eurocentric gaze, recognising the rich, complex artistic traditions of South and East Asia. Not as exotic ‘others’, but as vibrant cultures with their own histories, voices and power.

Further details

MET collection Teapot in the form of a man

Object information

- Mintons, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire

- 1884

- Bone China

- DA310058

by Laurie Bassam

Hexing (Wo Hing) of Hong Kong (和興) by Lam Qua II (林官) and

The Fourth Concubine of Hexing (Wo Hing) of Hong Kong (和興) by Lam Qua II (林官)

The curious case of the Brighton Lam Qua Portraits

During the 18th century, and until the British invasion of China in 1839, many British, European and American merchants and mariners who visited the port city of Canton (Guangzhou) commissioned portraits of themselves from Chinese painters. The artists consistently incorporated new materials and styles into their commissions. Oil on canvas portraits were especially popular in the early 19th century, and one Chinese artist, known as Lam Qua, emerged in the 1830s as the most sought-out portraitist by Westerners.

Western merchants also acquired portraits of Chinese merchants to take home, perhaps to prove their personal relationships with successful Chinese traders. After the British won the First Opium War in 1842, Cantonese painters such as Lam Qua expanded their trade to other cities, including to the new British colony of Hong Kong.

Today, many of the finest portraits of that period depicting both Chinese and Western men and women are attributed to Lam Qua. Each of these portraits raises fascinating questions about the identity of each subject and the painter, and about the relationship between sitter and artist. The two portraits in the collection of Brighton & Hove Museums are especially important in our understanding of the portraitist Lam Qua.

Each portrait has an inscription in Cantonese identifying the artist by the pidgin trade name “Lam Qua” and the Chinese name Guan Xiaocun (關曉村; Cantonese, Kwan Hiu-Chuen). It is generally accepted that there was more than one artist in Canton who used “Lam Qua” or a variant of the name, and that the famous portraitist Lam Qua came from a family surnamed Guan (關) in Guangdong province.

It has also been proposed that Guan Xiaocun could have been one of the Chinese names of that Lam Qua, since Chinese people, especially artists, used different names during their lifetime. Thus, these two portraits may have been painted by the famous Lam Qua. The date on the inscriptions dates the portraits to 1866-67 by which time Lam Qua would have been in his 60s. It is also possible that the portraits may be the work of a younger relative or descendant named Guan Xiaocun, who would presumably be another portraitist who used the Lam Qua name. Because researchers see subtle differences in style between these portraits and others that are more firmly attributed to the more famous, older Lam Qua, these two portraits have long been viewed as by this “Lam Qua II”. However, there are no other records of this artist, and these two portraits would be his only known works.

The inscriptions also identify the subjects as a Hong Kong merchant He Xing (Cantonese, Wo Hing) and his “fourth concubine.” Wo Hing was a popular company name in Hong Kong in the 20th century, but a merchant using this name does not appear in mid-19th century records of Western trade with China. The identity of the Wo Hing in this pair of portraits is thus not yet known.

In the painting he is portrayed in the winter dress of a civil official, with the insignia (badge, finial and necklace) signifying a status of fifth rank. Merchants in the late Qing dynasty regularly purchased civil official titles and were able to “advance” so quickly that these insignia were openly sold and easily replaced.

Although the inscription on the portrait of the woman states that she was Wo Hing’s fourth concubine, recent scholarship indicates that at least 14 other versions of this portrait – depicting almost the same woman’s face – exist today, and some are often mistakenly said to depict Rong Fei, the famous Imperial Consort of the Qing court.

Among these 14 however, this portrait has the most naturalistically rendered face. This Portrait of a Woman thus may either be a type used frequently in female portraits, or may be a portrait of an individual woman, which became the model for a type popularly used to portray the most famous beauty of the Qing Court.

Winnie Wong is Professor of Rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley. She is an art historian with a special interest in fakes, forgeries, and counterfeits. She has published a book, The Many Names of Anonymity: Portraitists of the Canton Trade (University of Chicago Press, available Jan 2026) which features an exploration of the multiple identities of “Lam Qua”.

Artwork details

- Hexing (Wo Hing) of Hong Kong 和興

- 1864

- Oil paint on canvas

- FA000631

Artwork details

- The Fourth Concubine of Hexing (Wo Hing) of Hong Kong, 和興

- 1864

- Oil paint on canvas

- FA000632

by Winnie Wong

Jolly Roger flag

“Underhanded, unfair, and damned un-English”

Jolly Roger Flag

This is the Jolly Roger flag of a WW2 submarine named Unbeaten, adopted by Hove in 1942. At the advent of submarine warfare in the early 1900s, Sir Arthur Wilson felt that submarine warfare was: “Underhanded, unfair, and damned un-English”. He suggested that enemy submariners should be hanged as pirates. Delighting in the comparison, the Royal Navy adopted the Jolly Roger flag for their submarines.

During the second week of March 1942 the Hove Borough Council ran a National Savings ‘Warship Week’ campaign to raise funds for the war effort, their target was £425,000, and on achieving this goal the town was able to adopt a warship. The final tally of funds raised was £521,000 and the submarine H.M.S. Unbeaten was adopted by Hove. Between December 1940 and July 1942, the H.M.S. Unbeaten had sunk the German submarine U-374, the Italian submarine Guglielmotti, the Italian sailing vessel V 51 / Alfa, and the Vichy-French merchantman PLM 20.

The handmade Jolly Roger flags were only allowed to be flown after the crew’s first successful patrol, and it would be officially presented to the commanding officer. It was subsequently taken out to sea on each patrol and, following each successful mission, the crew would sew on another emblem. The flag would be flown when entering harbour at the end of each patrol to signify their success. Each of the symbols signify different actions; the white bar means the torpedoing and sinking of an enemy merchant ship, the crossed guns means gun damage to an enemy vessel, and the ‘u’ shape with a line means torpedoing and sinking of an enemy submarine.

Shortly after their return to the UK, the mayor of Hove invited the commanding officer and some of the officers and crew to a private, celebratory, lunch. During this lunch the commanding officer presented the ships ‘Jolly Roger’ flag to the mayor for the townspeople of Hove.

Object information

- Flag

- 1940-1942

- Textile; Metal

- H1945.27

by Joanne Smith

India's Fighting Men postcard. Pavilion Grounds, Brighton

Light Sections by Edward Alexander Wadsworth

Dreams of the Machine: Power in Surrealism

Wadsworth’s Light Sections projects the power of machinery in his distinctive style. Abstract industrial shapes dominate in a seaside landscape. At first glance, the scene appears to consist of construction materials for a ship, but on closer inspection the wood bends in unnatural angles and the metal is contorted. Wadsworth paints the deconstructed ship with bold, angular lines which evoke industrial power. The objects mimic maritime machinery, but they appear deconstructed. The image Wadsworth has built is surreal, like a dream or an echo.

Wadsworth was born in Yorkshire in 1889. He studied engineering in Munich and later attended the Slade School of Fine Art. During the First World War he worked for the Royal Navy, painting dazzle camouflage on the ships. Dazzle painting consisted of complex geometric patterns that aimed to interrupt the enemies estimation of the range and position of vessels. This work is captured in Wadsworth’s painting Dazzleships in Dry Docks at Liverpool, 1919. His naval background inspired a maritime theme throughout his artistic career.

Dazzle camouflage is reminiscent of Vorticism painting, a movement which Wadsworth was a member of. Vorticism drew from Cubism and focused on the fragmentation of urban, industrial cityscapes. The movement was formed in 1914 and led by the artist and writer, Wyndham Lewis. The group was influenced by the Futurists and favoured bold colours and an angular style.

The Vorticist’s worked closely with poets such as T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. In 1915 the group produced the manifesto BLAST, which Wadsworth signed. The first edition of BLAST outlined the Vorticists’ appreciation of modern innovation. The movement rejected tradition and embraced industry, technology, and the future. Wadsworth was described by Sir John Rothenstein as ‘a true poet of the age of machines’.

In the 1920s, Wadsworth visited France and was inspired by Surrealism. He developed this into his style and his later works grew to include more abstraction. In Light Sections, he places jagged and inscrutable constructs within a seaside background, juxtaposing the power of machinery with nature. The blend of inspirations, from Vorticism to Surrealism, are evident in this late-career work.

Object information

- Light Sections

- 1940

- Tempera on panel

- FA000161

by Ana Symons

The Dutch Doll by Mark Gertler

The Dutch Doll, by Mark Gertler

Mark Gertler’s The Dutch Doll stands at the crossroads of restraint and intensity. Painted in 1926, this still life transforms a simple wooden toy into a figure charged with silent power. The doll sits motionless, yet its fixed stare meets the viewer’s gaze with unnerving strength. The stillness becomes an act of control—an assertion of form over feeling, of surface order concealing turbulent emotion.

Gertler, born in London’s East End to Polish-Jewish parents, knew what it meant to live between worlds. His early life was shaped by poverty, illness, and the challenge of navigating class and cultural barriers. At the Slade School of Art, he emerged as a prodigy with a precise and deliberate style. Yet beneath this formal discipline lay an intense emotional current. His life and art often wrestled with questions of mastery and vulnerability—who holds power, and who yields it?

In The Dutch Doll, power takes a quieter, psychological form. The painted figure is small and contained, but Gertler’s composition gives it authority. Angular lines, simplified geometry, and heightened colour create an image that is at once beautiful and oppressive. The doll’s unmoving body seems caught between object and being, suggesting both control and confinement. Its blank expression and sharp contours evoke the paradox of a world seeking order after chaos—the lingering emotional wreckage of the First World War, and Gertler’s own inner conflict.

This is not the power of domination, but of endurance. Gertler’s meticulous brushwork reflects a mind striving for balance against the weight of anxiety and isolation. Every edge and shadow feels deliberate, as though the artist could command meaning through precision alone. Yet, the more exact the form, the more fragile it appears. The painting’s power lies in the tension: in how stillness vibrates with suppressed energy, how simplicity hides turmoil.

Seen through this lens, The Dutch Doll becomes more than a study of objects—it is a meditation on human strength, fragility, and the quiet assertion of control amid uncertainty. Gertler transforms the inanimate into something almost spiritual: a moment of power contained, not expressed; felt, but never released.

Artwork details

- The Dutch Doll

- 1926

- Oil paint on canvas

- FA000157

- Donated by the Contemporary Art Society in 1943

by Yujin Son

My mother said, that I never should, play with gypsies in the wood.... wall hanging by Delaine Le Bas

More information to follow soon

Rucksack Toby by Richard Slee

Richard Slee: Rucksack Toby and the Art of Protest

How can a giant Toby jug be a piece of protest? In Richard Slee’s Mantelpiece Reports project—originally commissioned for Bolton Museum and later shown in at Hove Museum (2022)—the familiar Toby jug becomes a vessel for exploring class, taste, and the politics of everyday life. By scaling up and reimagining a humble domestic object, Slee invites us to question the hierarchies that divide art from craft, and working-class culture from the so-called fine arts.

Richard Slee, often called the “grand wizard of ceramics,” has been a leading figure in contemporary studio pottery for over four decades. Born in Cumbria in 1946, he studied at Carlisle College of Art and the Central School of Art and Design, graduating in 1970. After years balancing part-time teaching with his studio practice, he joined Camberwell College of Art in 1990 and became Professor of Ceramics in 1992. His work has since achieved international recognition, represented in collections across the UK, Europe, North America, and Asia—including the V&A, the Crafts Council, UCLA, and here at Brighton & Hove Museums.

At the heart of Rucksack Toby lies Slee’s fascination with the Mass Observation project, a pioneering social research movement founded in 1937 to document everyday British life. Its Mantelpiece Directive invited volunteers to describe what sat on their mantelpieces—those everyday shrines to personal memory and social aspiration. The findings revealed that the ordinary objects we live with are rich with symbolic meaning: they tell stories about who we are and what we value.

Slee also drew on the photographs of Humphrey Spender, who captured working-class life in Bolton during the 1930s for Mass Observation. Spender’s images, and the written mantelpiece reports, provided a lens through which Slee could reinterpret the Toby jug—not just as quaint kitsch, but as a witness to social history.

Traditionally, Toby jugs and porcelain figures have been synonymous with working-class homes, cherished as ornaments or symbols of modest pride. By transforming these familiar ceramics into monumental, witty sculptures, Slee upends their status. His oversized jugs and figurines mock and play with the snobbery that often separates “high” art from “low” culture. In doing so, Rucksack Toby stands as both celebration and protest. A joyful rebellion against class-based hierarchies in the arts. Proving that beauty, humour, and meaning can reside in even the most ordinary of objects; and that protesting the status-quo can come in many forms.

Further details

Watch Richard Slee at Hove Museum on the Latest TV YouTube Channel

Object information

- Richard Slee

- 1984

- Fired and Glazed Ceramics

- DA301640

by Laurie Bassam

#We Are Equal T-shirt and Protest Hoop Skirt by Momma Cherri

More information to follow soon

Lesbian Link banner

More information to follow soon

Landscape of a Dream by Eileen Agar

Landscape of a Dream, Eileen Agar

Eileen Agar (1899-1981) is a British artist who navigated her career through a male-dominated art world. She often worked with dream-like scenes and symbols of nature, blending the real and imaginary throughout her work. Her creative experiments make her one of the most pioneering British artists of her time.

Agar was a Surrealist artist. Surrealism was a 20th-Century movement that explored the unconscious, the irrational and the revolutionary in art, literature and philosophy (Surrealism | Tate). Surrealist artworks often depict dream-like scenes, with contrasting and confusing elements that challenge any rational narrative.

Agar worked alongside Surrealists such as Paul Nash (1889-1946) and Max Ernst (1891-1976), and her work was influenced by her personal relationships with these artists. She chose to become an artist, a powerful act of resistance at a time when society expected a woman’s principal role to be a mother and a housewife.

Agar’s work blended Surrealism with other art movements such as Cubism (Cubism | Tate) with its fragmented and abstracted forms. Her singular subversive technique was both powerful and bold, reflected in the bright colours and swirling patterns of Landscape of a Dream.

Nature played a large part in Agar’s work. Many of the abstract shapes in Landscape of a Dream allude to the natural world, like the blue fish-shaped details and spirals at the bottom of the painting. Agar collected shells and fossils and used the sea for inspiration throughout her career. She grew up in Argentina and in England, and the coast was significant for her throughout her life: its depth and mystery resembled the unpredictability of the unconscious. Landscape of a Dream can be perceived either as hermetic or freeing, allowing imagination to play a role.

Artwork details

- Landscape of a Dream

- 1984

- Oil paint on canvas

- FA001261

- Donated by Eric and Jean Cass through the Contemporary Art Society 2012

by Katie Mahoney-Roberts

Shepherd of the Pyrenees by Rosa Bonheur

Out Amongst the Crowd: Individuality and Empowerment

Rosa Bonheur was a powerful individual as well as a celebrated painter. She defied the constraints of her time. Her portfolio of work and the success of her career represent a life of protest against the misogynistic and homophobic standards of the 19th century. She built a successful career for herself as a woman and lived as a lesbian with her lifelong partner, Nathalie Micas. Micas was also a painter as well as a successful inventor, patenting the ‘Micas break’ for trains in 1862.

Bonheur was born in Bordeaux in 1822 and moved to Paris with her family in 1829. Her father was a landscape painter, and while he trained Bonheur, he struggled to make a living from his work and attempted to discourage her from becoming an artist herself. She ignored this advice and was committed to her practice. As an artist, Bonheur was dedicated to realism and made many preparatory sketches before embarking on a piece. Her favoured subjects were landscapes and animals.

She first exhibited work at the Paris Salon at the age of 19 in 1841. Her career continued to grow throughout the 1840s and she often exhibited animal paintings and sculptural work at the Salon. In 1848 she won a gold medal for her painting Bulls and Oxen (Cantal breed). This award led to a commission from the French State where Bonheur created Ploughing in the Nivernais, 1849.

Bonheur lived unconventionally, in a way which was earnest to her. She wore her hair short, and while she couldn’t live openly as a lesbian in her time, she was outspoken on female independence.

She made several trips to the Pyrenees with Nathalie and painted the many different animals and workers they met on her travels. Bonheur’s paintings championed working animals and rural life. In the Shepherd of the Pyrenees, Bonheur highlights the serenity of this natural landscape and portrays the flock with exacting detail. She foregrounds the black sheep of the herd, which urges the viewer to contemplate individuality and differences. The black sheep stands out from the crowd, yet it is still part of the flock. This idea is resonant in Bonheur’s life, as she both embraced her individuality and achieved a high level of success in her passion as an artist.

Artwork details

- Shepherd of the Pyrenees

- 1888

- Oil paint on canvas

- FA000323

by Ana Symons

Power to the People; Reproduction posters, flyers and photographs, 1960-2005

More information to follow soon

Activist how-to materials

More information to follow soon

Protest in Brighton, Protest Films 1899 - 2022

More information to follow soon