WW1 and the Royal Pavilion

During the First World War, the Royal Pavilion was converted into a hospital for wounded soldiers. It became one of the most famous military hospitals in Britain.

From 1914 to 1916 it was used for Indian soldiers who had been wounded on the battlefields of the Western Front. From 1916 to 1920 it was used as a hospital for British troops who had lost arms or legs in the war.

The Indian Hospital

The Indian Army played a vital role in the first few months of the war. At a time when Britain was still recruiting and training volunteers, soldiers from across the Empire came to fight in Europe and support the British cause. The Indian Army provided the largest number of troops, and by the end of 1914 they made up almost a third of the British Expeditionary Force.

Engaged in fierce fighting on the Western Front, the Indian Army inevitably suffered casualties. Medical facilities were urgently required, and it was felt that there were neither the facilities nor expertise in France. Brighton was chosen as the site for a complex of military hospitals dedicated to the care of wounded and sick Indian soldiers. Three buildings were given by the town authorities for this purpose: the workhouse (renamed the Kitchener Hospital), the York Place School, and the Royal Pavilion.

The Royal Pavilion was the first Indian hospital to open in Brighton. The former palace, along with the Dome and Corn Exchange, were converted into a state of the art medical facility in less than two weeks. New plumbing and toilet facilities were established, and 600 beds were set up in new wards. X-ray equipment was installed, and the Great Kitchen became one of two operating theatres. The Pavilion’s first patients arrived in early December 1914. Over the following year, over 2,300 Indian patients were treated.

But the hospital was not only designed to care for the men’s medical needs. An enormous amount of effort was taken in catering for the patients’ religious and cultural needs. Muslims and Hindus were provided with separate water supplies, and nine kitchens were set up in the grounds so that food could be cooked by the patients’ co-religionists and fellow caste members. Sikhs were provided with a tented Gurdwara in the grounds of the Pavilion, and Muslims were given space on the eastern lawns to pray to Mecca. Elaborate arrangements were made for those Indian men who died in the Brighton hospitals, 18 of whom died in the Royal Pavilion. Sikhs and Hindus were provided with a site for open air cremations on the Downs near Patcham, and Muslims were buried in a specially laid out cemetery in Woking near the Shah Jahan Mosque.

In late 1915 the British decided to redeploy the Indian Army in the Middle East, and most Indian soldiers were withdrawn from Europe. As a result, Brighton’s Indian hospitals gradually closed. The Pavilion was the last to close in January 1916.

Hospital for Limbless Men

In April 1916, the Pavilion reopened as a hospital for British amputees. This hospital treated over 6000 soldiers who had lost arms or legs during the war. Wounds were treated, and prosthetic limbs were fitted, but the limbless hospital did not simply care for the patients’ immediate medical needs. The Pavilion hospital was used for rehabilitation, and ensuring that the men had skills and purpose to live fulfilling lives after the war.

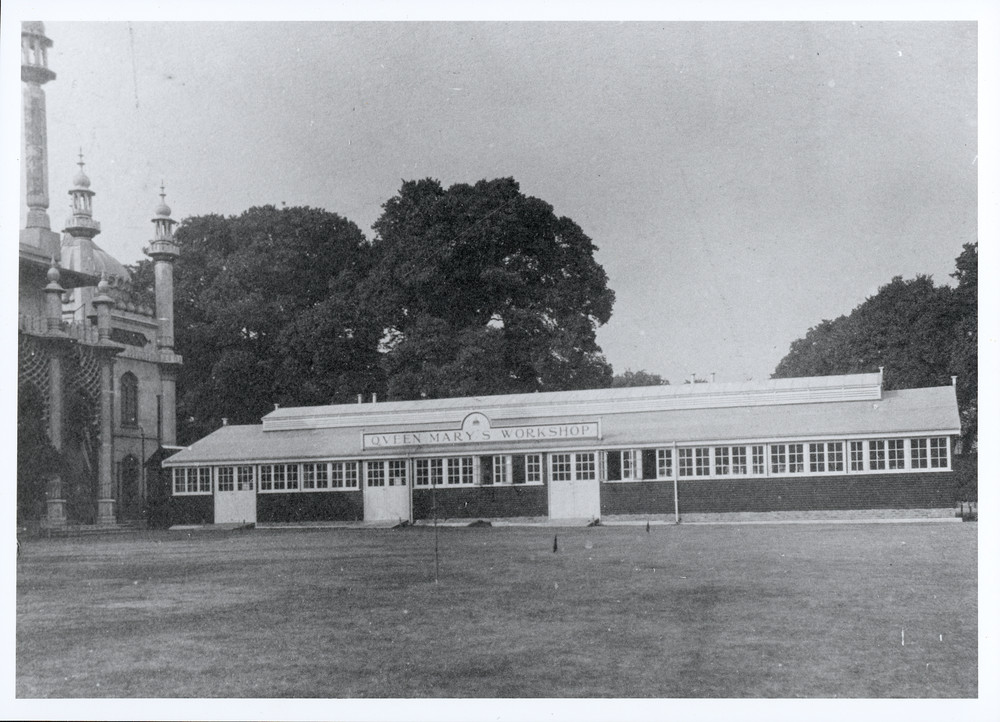

A workshop, named after Queen Mary, was set up in the grounds of the Pavilion. Bearing the slogan ‘Hope Welcomes All Who Enter Here’, the Queen Mary’s workshop was used to train the patients in new skills, such as engineering, grammar and cinematography. Men who had been unskilled labourers before joining the army would, having lost a limb, become skilled workers by the time they left the army.

The men were also given time and space to play sports and express themselves. The Sussex game of stoolball was regularly played, and the patients produced a monthly magazine, the Pavilion Blues, which was bought and sold in Brighton.

The limbless hospital received its last patients in July 1919. The Pavilion was finally returned to the people of Brighton in 1920. Having been occupied by the military authorities for almost six years, the building had suffered a good deal of wear and tear. The money paid in recompense by the War Office was used to fund some early work in restoring the Pavilion.

Monuments and Memorials

The Indian hospital is marked by two monuments in Brighton. The Chattri memorial stands on the spot on the Downs where Hindus and Sikhs were cremated. It is accompanied by a memorial maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission bearing the names of the 53 men who were cremated here. An annual remembrance ceremony takes place here every June, organised by the Chattri Memorial Group.

The Indian Gate at the southern entrance to the Pavilion was presented to the people of Brighton by the ‘princes and people of India’ as a gesture of thanks for the care provided by the town’s Indian hospitals. It was unveiled by the Maharajah of Patiala on 26 October 1921.

The story of the Indian Hospital is also told in the permanent Indian Military Hospital gallery in the Royal Pavilion.