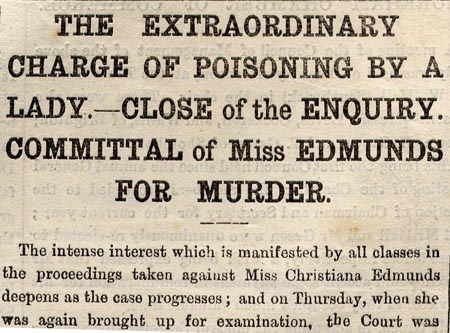

Love Letters and Hate Mail: Victorian Vinegar Valentines

Valentine’s Day is here again. To celebrate we revisit an earlier story, as a member of an old exhibition team introduced us to some unusual valentine cards from the collection.

Set with the most enjoyable task of discovering hidden histories of courtship and romance among Brighton & Hove Museums’ objects, the boxes of valentine cards in the museum’s reserve collections are an obvious first destination. Commemorating the day most enduringly associated with flirtation and love, and involving the transference of emotion into object form, the valentine card, with both commercial and personal stories to tell, is a most fitting location for focus in a project dealing with the material manifestations of the culture of attraction.

The many valentines in Brighton Museum’s collections date from the early decades of the 19th century through to the mid-20th century and represent, alongside single objects with unknown provenance, several donors’ personal collections. The range includes the touchingly inscribed alongside the never-used; the sweetly hand-made and the crassly mass-produced; single donated items and carefully compiled full albums.

A leather-bound album of valentine cards dating from around 1870, given to the museum anonymously in 1940, is of particular interest. Unlike the ladies’ scrapbooks of the 19th century, lovingly compiled with personally significant ephemera, each item in this album is tellingly marked with a serial number and with bulk prices, suggesting the object to be a stationery wholesaler’s sample book. The wide and varied range includes, among the many lacy, silvered, embossed, scented, cushioned, and delicate cards of cherubs, birds and flower garlands, a selection of cards of a very different type.

No laughing matter

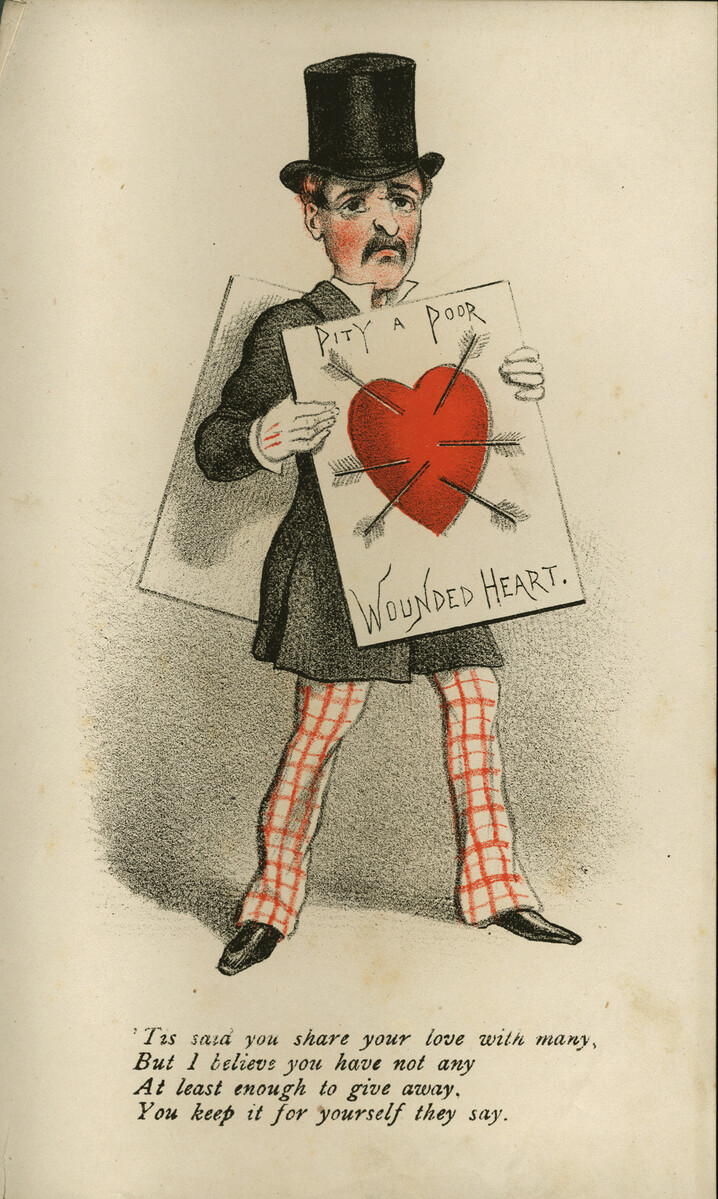

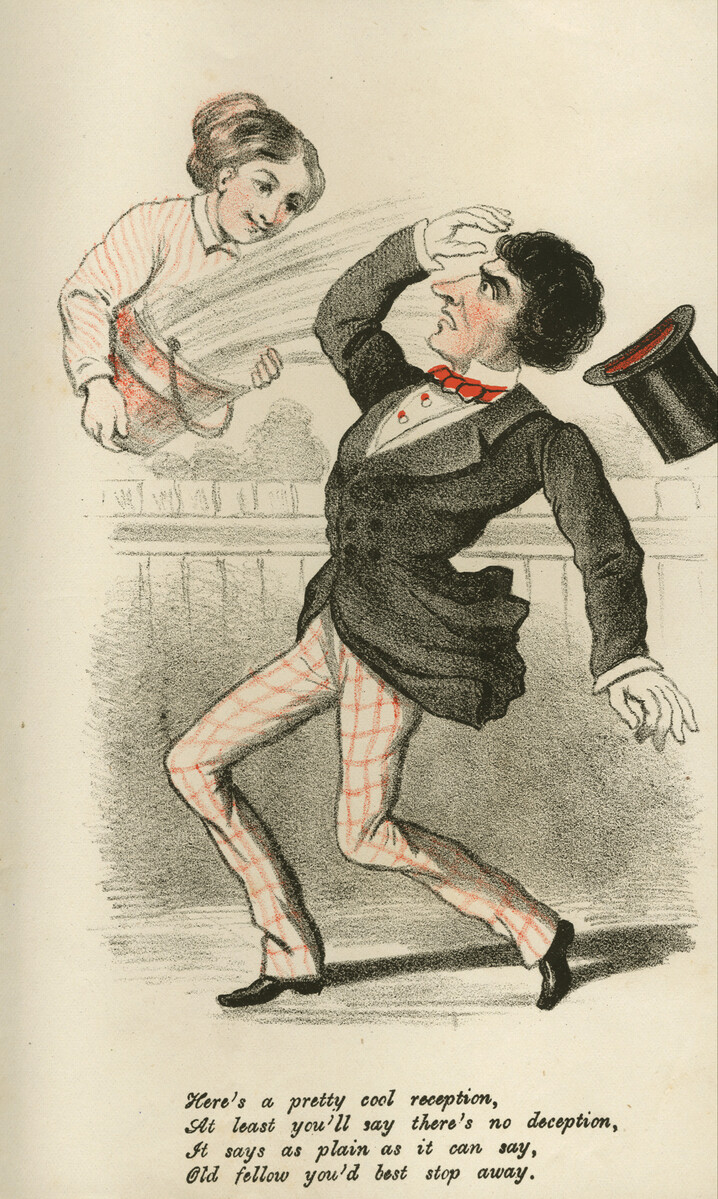

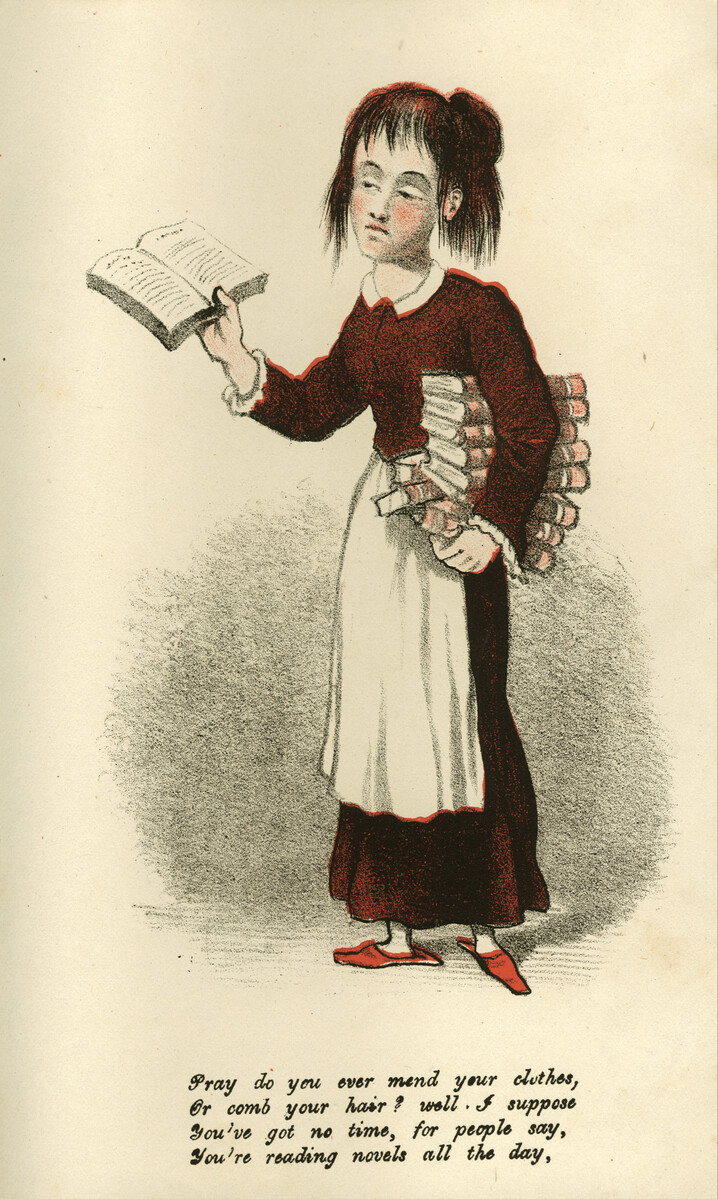

The forty-four distinctive valentines – the very antithesis of the sentimental and ornate majority – appear, tellingly, at the back of the album, and are marked with prices considerably lower than the other cards. They are in fact, not ‘cards’ at all in the sense of a stiff and folded object, but are rather thin, single sheets of printed paper. Displayed in stapled pamphlets or in tiered mounts to show the wide variety available without encroaching on the space of the more refined examples, these papers, with printed images and short captions or rhyming verse at their feet, are examples of what is sometimes referred to as mocking or ‘mock’ valentines. They are also referred to as ‘satirical’, ‘comic’ or, frequently, ‘vinegar’ valentines.

Vinegar valentines

This last title seems a most apposite description for, compared with the syrupy sweetness of the feathered and glittery majority of the collection, the flavour of the sentiment – or lack of it – on these distinctive artefacts is tart. Unlike the majority of the cards sent on Valentine’s Day today, their intention was not to flirt or to foster love but, at the very least, to chide, or at worst, to hurl abuse.

Vinegar valentines, in their various manifestations, performed a range of satirical functions from rejection of the recipients’ advances, to criticism of their faults, from drunkenness and vanity through to laziness and stupidity. The insults have specific rather than general aims, catering for a plethora of social ills. Victims can be as specific as the new father, the nagging wife or the unfaithful lover. The market for these products was clearly intended to be very wide as their range of insults.

Love-sick notes

The lesser documented history of mock valentines

The 19th century’s valentine ‘craze’, with its enormous commercial production and consumption of valentine cards is well known. However, the practice of sending what might be better called hate mail on the day of love is less well documented, has left fewer artefacts behind and no longer continues as a tradition. Although fewer vinegar or vulgar valentines survive today, this is not representative of their popularity during the Victorian period. Ruth Webb Lee, writing on the history of valentines, notes that by mid-century the comic valentine trade, at least in America, represented about half of all valentine sales. If we assume that the British comic valentine trade followed suit, then we can extrapolate that by the 1870s, when the sample book was being offered to stationery suppliers, as many as 750,000 insulting valentines were being sent each year.

Frank Staff, a postcard and valentine historian, suggests that few examples exist in museum collections because, ‘as a rule, they were used more by the lower classes, and by a section of society unable to keep souvenirs of this type over the years, unlike the more costly items which were put away and treasured for their sentiment and beauty by the more well-to-do and middle class families.’ Regardless of class, it also seems unlikely that the recipient of such a card would wish to cherish it by pressing it into an album. As a first-hand example of how such a valentine might be disposed of, Flora Thompson, in her thinly-fictionalised memoir, Lark Rise to Candleford, recalls receiving a particularly vicious example. Featuring a crudely-drawn printed caricature of a postmistress (reflecting her occupation), the valentine included a cruel verse and personalised insulting inscription commenting on her perceived ugliness. Thompson records that it was promptly thrown into the fire and kept a secret.

Cheap insults

Such cheap jibes were inexpensive to buy and even cheaper to send. In the days before stamps, when letters were paid for on delivery, the recipient of such a valentine could have insult added to injury by having to fork out for the privilege of being abused! Even after the introduction of postal prepayment, Flora Thompson noted that many of these cards passed through the post office unstamped.

Anonymity

The mail service also helped preserve the anonymity of the card’s sender, for then, as now, it was usual for valentines to be sent without a signature. What could be a charming guessing game with a sentimental valentine would be cruelly inverted with its vinegary opposite, not least because so many of the verses suggest a collective voice. Rather than simply one-to-one communication, the cards deploy the tactics of hiding the sender behind majority opinion. The terms ‘we’, ‘us’ and ‘everyone’ appear frequently in the insults, suggesting that the offending vice, whether it be pride, ignorance or hen-pecking, was not only noticed by the anonymous sender, but also by the larger community. It is worth noting that these cards were not sent privately between lovers or spouses, as traditional doting valentines are, but by members of the public offended by more general transgressions of propriety. They could be just as likely sent to an employer, teacher or neighbour as to a (former) loved one.

A gendered affair

The gender aspect of the cards is also intriguing. Historians of greetings cards are all agreed that observation of St Valentine’s Day is a particularly feminine phenomenon, as with general card buying and sending. Although there are no firm statistics for the 19th century, scholars of card culture, such as Barry Shank, have claimed that in the 20th century ‘nearly 80% of all greetings cards are bought and sent by women’. Certainly, in the 19th century, Valentine manufacturers defined and addressed women as the chief recipients and senders of sentimental cards. What is not known is the gender proportion of the market for vicious valentines. Clearly, judging by the cards themselves, they were made to be sent and received by women and men. Insulting valentines thus seem to open a space for men to play a part in a feminised ritual while simultaneously offering women a licence to misbehave.

Love’s ruin, criticism of the vinegar valentine

Spitting, scratching and clawing cards are a far cry from the pious and saintly origins of St Valentine’s Day, and this did not go unnoticed. Public reactions to the vinegar valentine phenomenon in the 19th century provide valuable insight into the reception of cards similar to those in Brighton Museum. Condemned by the press on both sides of the Atlantic, comic valentines were described in tones of moral outrage and variously labelled as ‘filthy’ and ‘nauseating’. Such cards were blamed for a degree of moral depravity and anti-social behaviour including, in the New York Times on February 15th 1866, the unlikely assertion that they encouraged ‘a fearful tendency to the development of swearing in males of all ages’. There were also more serious consequences to the sending of insulting cards, most significantly and sadly in the case of the ‘fatal valentine’ of 1847, where a woman in New York City overdosed on laudanum after receiving a mean valentine from a man who had led her to believe that he was interested.

The fall from fashion

Vinegar valentines were blamed for taking over and ruining a once sacred, romantic holiday. It was unanimously observed that the valentine, through commerciality or low humour, had become vulgarised. What is not clear, however, is whether this debasement was a symptom or a cause of its fall from grace. In the later years of the 19th century, the decline of the fashion for sending valentines of all types was as sudden as its rise. Some, such as a writer in The Daily Telegraph, suggested that ‘facetious vulgarity’ had been its killer, while others, such as the Company of Old English Valentine Makers, suggested that the tradition died out from a process of natural decay. Certainly, despite evidence that the custom for cheeky post continued through Edwardian times and beyond, in the diluted form of the comic postcard and cheap seaside caricatures, the large-scale commercial practice of sending poison-pen letters on St Valentine’s day has, thankfully, disappeared.