This is a legacy story from an earlier version of our website. It may contain some formatting issues and broken links.

It’s a great privilege to be part of the conservation team at the Royal Pavilion and we wanted to share a little of what we do with you.

The Conservation team includes specialists in Buildings, Objects, Gilding, Paper, Glass and Paintings Conservation, three Assistant Conservators and Conservation Technicians and as a department we are responsible for the preservation, conservation and restoration of the buildings and collections, ensuring that they are safeguarded for present and future generations.

The Royal Pavilion and Museums consist of five different sites with a broad range of collections in each. These are the Booth Museum of Natural History, Preston Manor, Hove Museum, Brighton Museum and the Royal Pavilion.

The work we undertake is varied and interesting and it’s a pleasure to work in such inspiring surroundings.

Anne Sowden – Decorative Artist and Glass Conservator

I am Anne Sowden and I have worked in the department as Decorative Artist and Glass Conservator for 30 years.

After completing a degree course in Fine Art (Painting), I worked in museums and trained in conservation. I then worked in the ceramics industry as a designer dealing with both the creative and technical sides of the process.

My role here involves the conservation, restoration and recreation of decorative schemes. I also look after the chandeliers and lanterns in the Royal Pavilion. All of this can only be undertaken after careful research.

At present, I am working on the Saloon restoration project. I have designed the carpet, based on a fragment of the original Saloon carpet and on documentary and visual evidence. I am now recreating the hand painted wall decoration. A rigorous study and analysis of the original fragments of the 1822 Robert Jones scheme have informed the work.

Andy Thackray – Objects Conservator

I’m responsible for the conservation of 3D objects from the RPM collections. With such broad and eclectic collections, this means I get to work with a wide range of objects and materials. Objects can range from taxidermy from the Booth Museum, to furniture from the Royal Pavilion, silver giltware from the Decorative Arts Collection, historic toys from Hove Museum or mummified animal remains from the Egypt Collection. My work is generally driven by major redisplay projects, exhibitions work, and preventive conservation priorities.

I am also responsible for managing the Assistant Conservators and Collections Care team who carry out vital preventive conservation work to keep the collections in the best condition possible for future generations to enjoy.

Amy Junker Heslip – Paper Conservator

As the paper conservator at Royal Pavilion & Museums I am responsible for looking after all works on paper in the collection. This can vary from archive material, photographs, historic wallpaper, prints, drawings, pastels and more!

My days are varied and can involve tasks such as small repairs in situ of wallpaper that may have been damaged around the Pavilion or getting works ready for in house exhibitions or external loans — I’m currently working on loans to Tunbridge Wells, Paris and New York. My days are also spent working on my rolling programme of rehousing and conserving works in the collection which is curator led. I might also be carrying out handling training for in house staff and volunteers, giving a Bite-sized Talk in the museum or working with the rest of the conservation team on a large project. At the moment the Saloon project is keeping everyone busy but I suspect another of the team will write more about that in their blog.

In short, it’s a busy, wonderful place to work. I come across some fantastic and fascinating objects and get to work pretty closely with them. I look forward to sharing more about that with you soon.

Hannah Young – Assistant Conservator

I’m an Assistant Conservator at the Royal Pavilion & Museums, concentrating on the remedial conservation of objects.

I am lucky enough to work on a broad variety of objects and different materials from the collections which spread over the five museums.

My material specialism is in metalwork conservation, of which there are many objects to keep me busy, but I also work on other objects ranging from toys and furniture to the repair of taxidermy birds and animals, which is a new interest for me.

I am currently assisting in our main conservation project which involves the restoration of the Saloon, one of the principle rooms in the Pavilion. Through this I am learning to water gild under the instruction of the Pavilion’s Gilding Conservator.

Hannah Young, Assistant Conservator

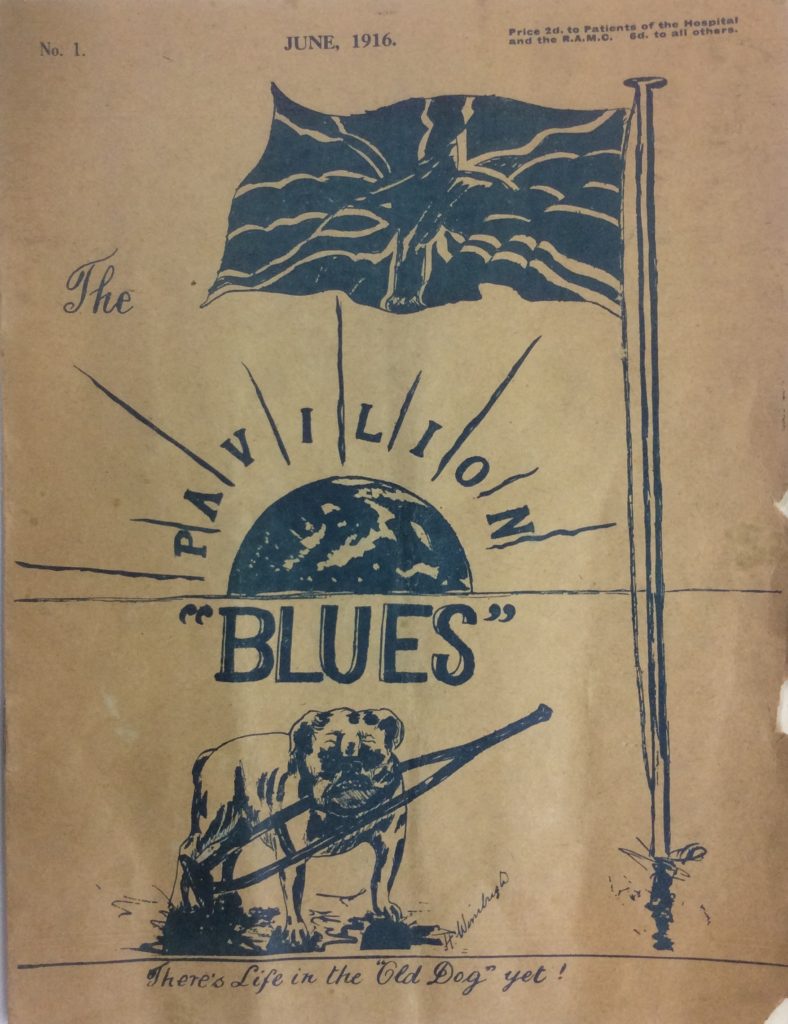

The 11th, 12th and 13th Royal Sussex Battalions were together known as ‘The South Downs’ Battalions’. They were ‘Pals’ battalions, made up of men who had enlisted together in local recruiting drives, with the promise that they would be able to serve alongside friends, neighbours and colleagues. When such batalions suffered a high casualty rate in action, it had a devastating effect on the towns and villages that the men came from. 70% of the men killed at the Battle of Boar’s Head were known to have been born in Sussex, and many more would have been residents. 30 June 1916 passed into local public consciousness as ‘The Day Sussex Died’, a comment which originally came from a veteran of the battle.

The 11th, 12th and 13th Royal Sussex Battalions were together known as ‘The South Downs’ Battalions’. They were ‘Pals’ battalions, made up of men who had enlisted together in local recruiting drives, with the promise that they would be able to serve alongside friends, neighbours and colleagues. When such batalions suffered a high casualty rate in action, it had a devastating effect on the towns and villages that the men came from. 70% of the men killed at the Battle of Boar’s Head were known to have been born in Sussex, and many more would have been residents. 30 June 1916 passed into local public consciousness as ‘The Day Sussex Died’, a comment which originally came from a veteran of the battle.