This is a legacy story from an earlier version of our website. It may contain some formatting issues and broken links.

One hundred years ago this month Russia’s October Revolution was launched in Petrograd (now known as St Petersburg) and changed the course of world history.

1300 hunded miles away at Preston Manor in Brighton, Ellen Thomas-Stanford found herself uniquely close to the uprising as her morning post bought first hand reports written in cinematic detail. More shocking still, within a year a dear friend’s niece would die in a hail of bullets alongside Tsar Nicolas II, the last reigning Romanov.

The home front: Brighton 1917

Ellen Thomas-Stanford & ‘1917-18’ scrapbook

Ellen Thomas-Stanford’s five large scrapbooks compiled between 1914 and 1919 are an extraordinary archive. The rarely opened pages positively sing with history made fresh.

Life in Brighton in 1917 was tougher than we can imagine, even without violent revolution on the streets. The First World War, so boldly entered, had been raging three long years. In April 550,000 tons of shipping was sunk by enemy submarines — disastrous for a country reliant on imported food. Even the wealthy were affected by shortages.

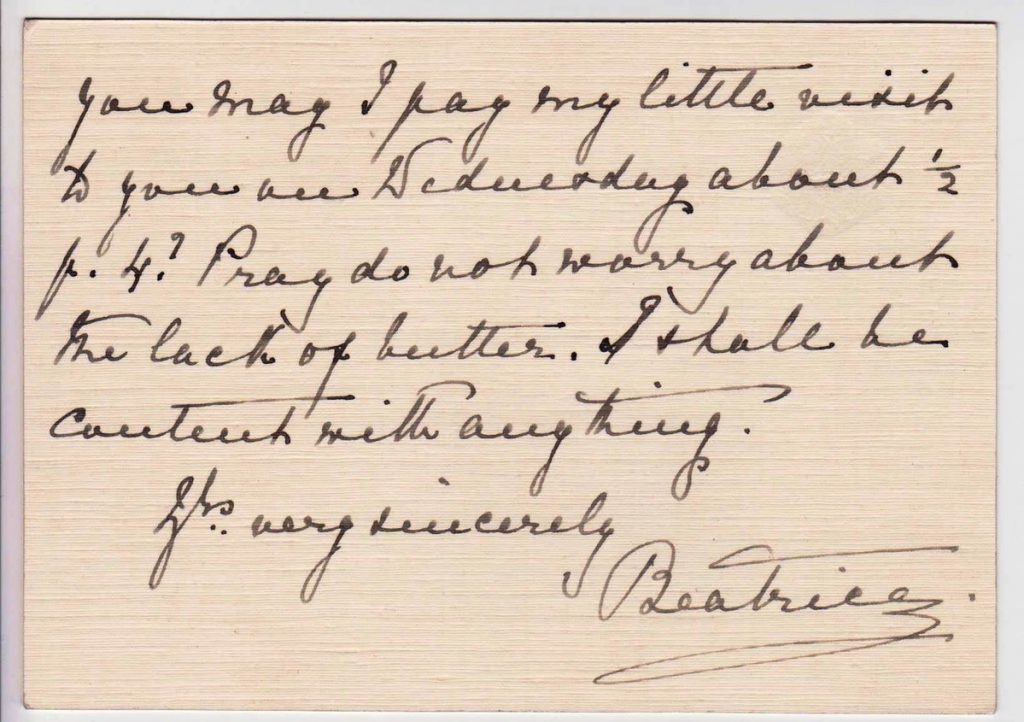

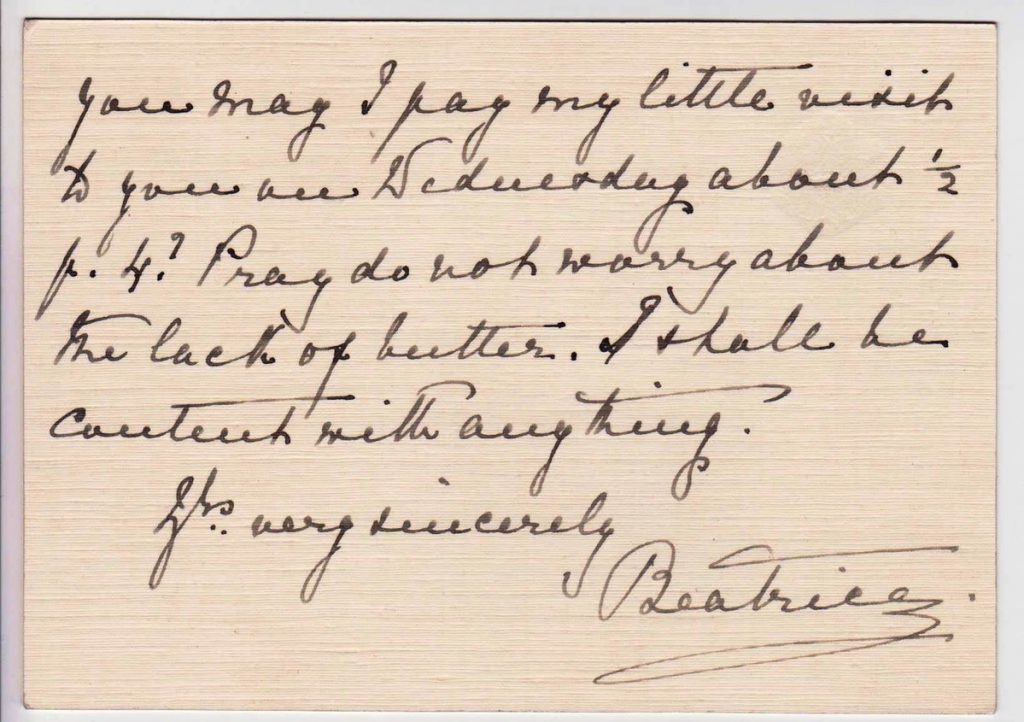

‘Please do not worry about the lack of butter,’ writes Princess Beatrice to Ellen before visiting to take tea. ‘I shall be cautious with everything.’

Princess Beatrice note to Ellen Thomas-Stanford regarding butter shortage

Postcard: ‘A Broadside from our land-ship’

Ellen’s comfortable life did not spare her from heartache. Sadness seeps into her 1917 scrapbook as page after page of black-edged mourning notepaper reports deaths of friends’ sons, nephews and husbands. In a snapshot of the age there are newspaper cuttings: mostly obituaries, letters from the Red Cross expressing thanks for fundraising, a postcard of a tank — an invention so new the machine barely had a name beyond, ‘our landship’. A colourful notice bearing the flags of the allies declares ‘A Solemn Oath’ that the signatories will swear not to ‘knowingly purchase anything made in Germany’ or ‘transact business with or through a German for 10 years after peace is declared’. Carefully pasted as a keepsake, the notice is unsigned.

The October Revolution: Petrograd 1917

In the autumn of 1917, peace must have felt like an unimaginable dream. As today, the leaves on the great trees in Preston Park were beginning to fall heralding yet another bleak winter of war on the home front. In Petrograd meanwhile, Ellen’s correspondents, Colonel ‘Croppy’ Henry Vere Bennet and Mr. Oswald Rayner of British Intelligence were living a hair-raising existence and preparing for the bite of the fierce Russian winter described in February 1918 by Croppy:

‘Cold here is normal but we had a fearful 3 days blizzard and furious snow storms which has upset even the Russians. We had 43° of frost i.e. 13° below zero for three days and the wind is what makes this place the limit…the streets are baulked up high with mounds of snow, high as a man’s head, which no amount of work could remove.’

Lieutenant Colonel Benett in the uniform of Aide de Camp to Major R Gillespie, Bombay late 1880s

Revolution in October bought disorder and hardship.

‘There is no electricity, candles cost a fortune and are of very inferior quality. Oil is equally scarce and dear. Bread is very scarce & bad & contains much straw and “foreign matter” which causes much illness especially amongst children & old people & now an outbreak of typhus, which after all is not surprising as the intake of water supply is well below the stream of output of the sewage of the city.’

Croppy reports a severe shortage of meat, vegetables, potatoes and eggs: ‘I’ve not seen an egg since October.’

The October Revolution began in Petrograd on the old Russian calendar date of 25 October (7 November in the UK). Led by Vladimir Lenin, Bolshevik Red Guards captured the Winter Palace– ‘our Buckingham Palace’, as Croppy clarifies for Ellen.

‘The Winter Palace is pitted all over with bullet holes, like the plums in a pudding, & nearly every one of its hundred windows is patched up with paper.’

On the spot while revolution raged, Croppy and Rayner kept Ellen informed of events.

‘On Tuesday 6th November, the uprising of the Bolsheviks which had been threatening for a week or more came to a head. The whole situation resembled a cauldron full of seething ingredients which still refuse to combine or amalgamate.’

Rayner, about who hangs much mystery regarding his role in the death of Rasputin in December 1916, was briefly back in London but writing on 22nd September 1917 he informs Ellen: ‘I am now busily engaged in active preparations for my return journey to Petrograd.’

Ever the Secret Intelligence Service officer he writes sparingly. However he can’t resist letting Ellen know he has been asked to ‘make a study of the work carried on in quite a new department (for me) at the War Office.’

At 28 years of age Oswald Rayner comes across in letters held at Preston Manor as a man of immense self-confidence and poise. He was a brilliant Oxford scholar, fluent in Russian, French and German, belying his humble origins as the son of a Staffordshire draper. In 1917 Rayner was in the prime of life and diligently acting upon whatever daredevilry his country asked of him.

On 26 September he tells Ellen:

‘I am making the necessary preparations to be able to leave on October 1st – these were my instructions. Further details will depend on the next date of sailing of H.M.S ‘Hush-Hush’! As she is called.’

Rayner’s exploits and evident cool head under pressure gives the impression that he was something of a James Bond of the First World War. If the final assassin’s shot that finally ended the life of Rasputin was fired from Rayner’s Webley revolver, as some historians believe, then the picture is complete.

Oswald Rayner died in 1961 leaving instructions that his private papers be destroyed. However a paper trail remains in the outpourings of his heart and reportage of Russian matters to Ellen Thomas-Stanford.

Russia’s revolutionary women

On arrival in Petrograd in the heat of revolution, Rayner reported:

‘There is virtually no government and public business is consequentially at a standstill. We seem to be drifting headlong into utter chaos with never a straw to cling to. Any hope that is left is centred on the proverbial miracle that is always supposed to come to Russia’s aid in her severest extremities.’

Coming to Russia’s aid at this time of crisis were an extraordinary band of soldiers, the Women’s Battalion of Death. Croppy met these all-female combat units out on manoeuvres. Fascinated, he was eager to share his thoughts with Ellen in Brighton.

The Women’s Batallion of Death, 1917

To illustrate he sent two postcards. One he marks with symbols so Ellen might see the Colonel and her Adjutant with whom he spoke.

‘The former is the widow of a soldier and was herself five times wounded…she is of peasant origin and is now in hospital suffering from shock. The adjutant, a girl of 18 only, I found in temporary command. Quite pretty, the daughter of an Admiral, well educated, speaking English fluently and in Petrograd society.’

Russian military women

A military man himself Croppy writes admiringly of these female fighters.

‘They were occupying a sector of the front line and do everything for themselves. I found them quite smart, discipline better than some regiments of men, sentries and snipers alert and all seemed in deadly earnest.’

Safe in the quiet surrounds of her ancient family home, Ellen must have shuddered at Croppy’s description of life in Petrograd sent 9 November.

‘For some time past life here has been unsatisfactory and most unsettled. The police disappeared in our first revolution and the militia which replaced them has gradually melted away. Neither life nor property has been safe and there is no one to turn to for protection. People are robbed not only in the slums but also in the streets of the best quarters of the city. Women are stripped of their boots, their furs or a good cloak in broad daylight…houses are entered and everything removed which takes the fancy of the visitors…last week four-hundred robberies were reported in one night.’

Ellen Thomas-Stanford’s friends in Brighton

Black edged letter

Reading Ellen’s collection of black-edged letters from October and November 1917 is a sobering task. One hundred years on the bitterness and animosity felt towards the German people has the power to shock.

J.N Langley writes from Hedgerley Lodge, Cambridge on 25 November.

‘I do not understand the frame of mind of those who are ready to renew relations with Germans after the war. The pests should be treated as such.’

A friend writing from Barrowfield Lodge, Brighton on 11 October places blame at the top:

‘It is too terribly sad these many bright young lives one after another be sacrificed, and to think that all this misery is caused by one wicked man, the German Emperor.’

A matter perhaps not considered by this friend was Ellen Thomas-Stanford’s astonishing closeness to the ‘wicked man’ for she regularly admitted into her home Kaiser Wilhelm’s aunt, Princess Beatrice.

Haemophilia: Queen Victoria’s genetic legacy

Beatrice’s mother, Queen Victoria, famously gave birth to a bloodline of descendants destined to be reigning monarchs of Britain, Germany, Russia and Spain at the start of the new century.

Victoria’s lineage bought with it the infamous gene for haemophilia, the devastating blood disorder that would shape the European world map almost as much as war.

Ellen’s friend Beatrice was Victoria and Albert’s fifth daughter and youngest child. Along with her sister Alice she was a carrier for haemophilia, so when she married the German Prince Henry of Battenberg in 1885 the health of any children yet to be born was already imperilled.

Sisters Helena and Louise, who also visited Preston Manor, were not carriers.

Both Beatrice’s sons, Lord Leopold Mountbatten and Prince Maurice of Battenberg, were haemophiliacs and both would die young. Maurice was killed on active service at the Battle of Ypres in 1914, fighting for the Allies irrespective of his German pedigree. Leopold, always the frailer brother, died aged 32 in 1922 the result of an attempted hip operation – certain death for a haemophiliac whose blood fails to clot.

Ellen must have felt Leopold’s death keenly, for he died one month before her beloved grandson, Vere. In many respects Leopold was much like a second grandson to Ellen. The pair corresponded by letter, Leopold writing from his quarters at Clock Court, Kensington Palace.

Of his brother‘s death he writes,

‘There is little comfort in knowing he died a soldier’s death, which I am sure he would have wished but it has been an awful blow to me all the same.’

We can’t know if Ellen and Beatrice talked about world politics. The tone of their letters suggests they kept to uncontentious subjects. Perhaps some subjects were too painful to commit to paper even at this time of revolution, war and family deaths.

Rayner, Rasputin and Russia’s royals executed

The most prominent death linked to Ellen’s circle of friends was one unmentioned in any letter I have yet found between Beatrice and Ellen.

Not written about but surely talked of at Preston Manor were the events of 17 July 1918. On that date Beatrice’s niece, Alexandra (known as Alix), who had married Tsar Nicholas II in 1894 and become Empress of Russia, was executed by Bolshevik troops alongside her husband and their five children. A 200 year old Romanov dynasty was wiped out in one hail of gunfire.

Tsarina Alix’s concern for her young haemophiliac son, the Tsarevitch Alexis, had led directly to the entry of faith healer Grigory Rasputin into the royal household.

One year before the massacre of the Russian royal family, Croppy makes reference to one of the many unorthodox medical practitioners enlisted by the Romanov family in the vain hope of a cure.

In a letter to Charles Thomas-Stanford dated 18 June 1917 he writes: ‘I won’t give his name but I have known something about it in the course of my work.’

Croppy refers to the mysterious man as ‘a strange personage, a Thibetan (sic) doctor,’ who historians identify as Siberian born Pyotr Badmaev, friend of Rasputin.

‘Whether Rasputin was his agent or he Rasputin’s no one can say definitely,’ Croppy writes adding with distain, ‘he is strongly pro-German.’

Rayner’s old Oxford University friend, Prince Felix Yusupov, in whose palace Rasputin was murdered, gave a newspaper interview in March 1917 claiming Rasputin and Badmaev fed drugs to Tsar Nicholas, rendering him useless. Croppy mentions the story in his letter to Charles, ‘with the increasing rumours of the drugging on the Emperor for some time past.’

War’s end and aftermath

Croppy and Rayner continued to keep the Thomas-Stanfords informed of world news after the war ended in 1918. A letter from Croppy written from his residence at 8 Challoner Mansions, West Kensington on 2nd October 1919 is especially intriguing.

Croppy and Rayner continued to keep the Thomas-Stanfords informed of world news after the war ended in 1918. A letter from Croppy written from his residence at 8 Challoner Mansions, West Kensington on 2nd October 1919 is especially intriguing.

‘I am very busy at the W.O. (War Office) finishing up writing reports and appreciations of my years’ work in North Russia. When we meet I have much to tell you which it was quite impossible to write or hint at on paper.’

As for Oswald Rayner, his whereabouts become international: Japan, the United States, and Sweden – and in March 1919 he was writing from the Headquarters of the British Military Mission to Siberia.

Turning 30 he writes, ‘my future movements are shrouded in mystery,’ and it seems he had moments of homesickness confessing to Ellen:

‘I am accustomed to being abroad, as you know, and never before have I experienced such an overpowering “nostalgie”. I want to be with my friends, my real friends. How good it would be to be at Preston for a weekend. When oh! When will it be?’

Promotion and honours

Like his friend Rayner, Croppy was fascinated by Russia and its peoples.

‘There are very many strange things in this country and it has taught me a great deal about human nature and its weaknesses.’

Croppy was honoured internationally for his contribution to the war effort.

He sent Ellen postcard pictures of his Russian medals, the Order of St Stanislas 1916 and the Order of St Anne 1918 awarded for his efforts in improving the Allied-Russian communications system.

The French awarded him the Légion d’Honneur, Croix d’Officier in October 1918.

Naval & Military Club letter

In 1918 Croppy was made one of the first Commanders of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in recognition for his services in Russia, an honour he accepted with modesty. Writing on a Naval & Military Club card dated 20 June 1918 he thanks Ellen for her ‘pleasing’ congratulations. However he prefers to speak of Rayner’s promotion to the rank of Captain, applauding the capability of the younger man rather than basking in personal honours.

Henry ‘Croppy’ Vere Fane Benet died in March 1931 the year before Ellen Thomas-Stanford, his fondly addressed, ‘Mrs Squire’ and recipient of his vivid letters from revolutionary Russia.

Paula Wrightson, Venue Officer, Preston Manor

More information

I’m writing this as someone whom experienced the Museum Mentors summer project and of course a client of the art group the museum offers to those with either or both mental / physical struggles. I say of course as I have my own website and following and I’m open about my issues to help fight stigma.

I’m writing this as someone whom experienced the Museum Mentors summer project and of course a client of the art group the museum offers to those with either or both mental / physical struggles. I say of course as I have my own website and following and I’m open about my issues to help fight stigma.