History

The Royal Pavilion was constructed as the seaside pleasure palace of King George IV. But it has seen many twists and turns throughout its long history.

George comes to Brighton

In the mid 1780s George, Prince of Wales, rented a small lodging house overlooking a fashionable promenade in Brighton. Brighton was developing from a decayed fishing town to an established seaside retreat for the rich and famous, being close to London.

It also proved popular for the therapeutic health-giving sea water remedies made famous by Dr Richard Russell, a physician from nearby Lewes.

The prince had been advised by his physicians to benefit from Brighton’s fortunate climate and to try out the sea water treatments, which included ‘dipping’ (total body immersion into the salt sea water).

Fashion & Frivolity

Brighton suited George who was a vain and extravagant man with a passion for fashion, the arts, architecture and good living. He rebelled against his strict upbringing and threw himself into a life of drinking, womanising and gambling.

This decadent lifestyle combined with his love of architecture and the fine and decorative arts – his residences in London and Windsor were like immaculate sets to show off his superb collections – resulted in his incurring heavy personal debts.

In 1787, after much pleading and many promises by the Prince of Wales, the House of Commons agreed to clear his debts and increase his income.

George hired architect Henry Holland to transform his Brighton lodging house into a modest villa which became known as the Marine Pavilion. With his love of visual arts and fascination with the mythical orient, George set about lavishly furnishing and decorating his seaside home. He especially chose Chinese export furniture and objects, and hand-painted Chinese wallpapers.

In 1808 the new stable complex was completed with an impressive lead and glass-domed roof, providing stabling for 62 horses.

The Royal Pavilion Grows

In 1811 George was sworn in as Prince Regent because his father, George III, had been deemed incapable of acting as monarch.

At that time the Marine Pavilion was a modest building in size, not suitable for the large social events and entertaining that George loved to host.

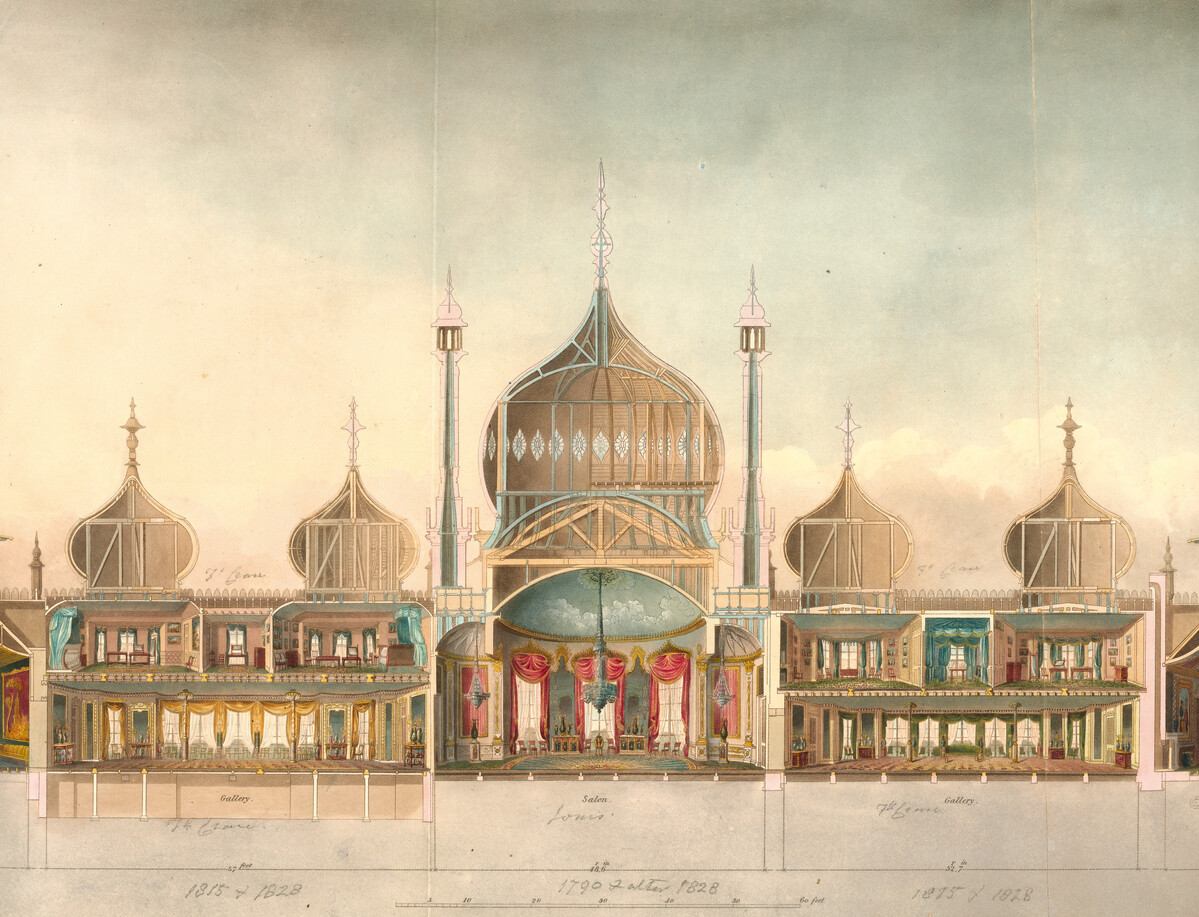

In 1815, George commissioned John Nash to begin the transformation from modest villa into the magnificent oriental palace that we see today.

This stage of the construction took a number of years. Nash superimposed a cast iron frame onto Holland’s earlier construction to support a magnificent vista of minarets, domes and pinnacles on the exterior. And no expense was spared on the interior with many rooms, galleries and corridors being carefully decorated with opulent decoration and exquisite furnishings.

Comfort & Convenience

George was determined that the palace should be the ultimate in comfort and convenience.

Particular attention was paid by his architect and designers to lighting, heating and sanitation, as well as to the provision of the most modern equipment of the day for the Great Kitchen.

Prosperity for Brighton

George’s presence had an enormous impact on the prosperity and social development of Brighton from the 1780s.

Brighton’s population grew significantly, from around 3,620 inhabitants in 1786 to 40,634 in 1831. The rebuilding of the prince’s home provided work for local tradesmen, labourers and craftsmen.

The presence in the town of the court, George’s guests, members of society and the Royal Household provided invaluable business for local builders and the service industries.

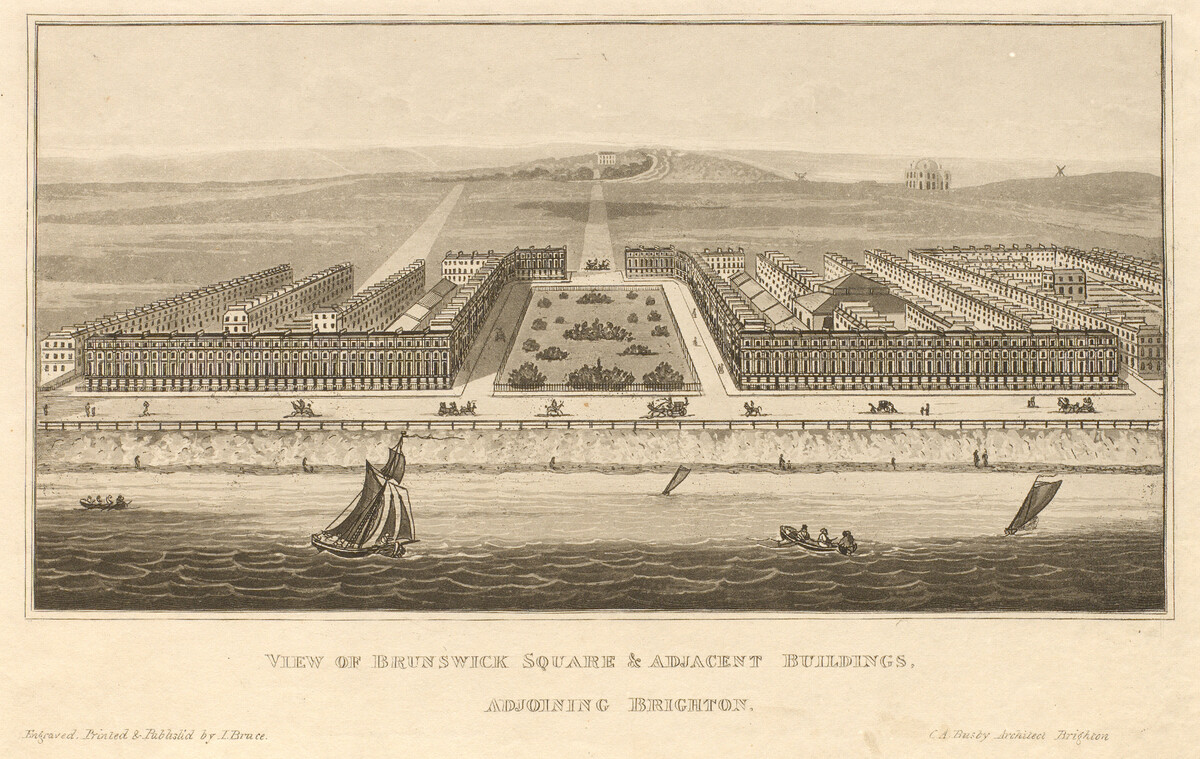

Many of the handsome seafront squares and crescents that still stand today are attributable to the arrival of George IV and the fashionable Regency era.

Amon Wilds and Charles Busby, architects of the day, built impressive estates in Kemp Town to the east and Brunswick to the west in Hove. Both are now outstanding Grade I listed conservation areas and underpin the look and the feel of modern Brighton & Hove.

George became king in 1820. However, due to increased responsibilities and ill-health, once the interior of the Royal Pavilion was finally finished in 1823 he made only two further visits (in 1824 and 1827).

On his death in 1830, George was succeeded by his younger brother, William IV.

William IV

William IV was a popular and affable king and continued to visit Brighton and stay at the Royal Pavilion. As George IV had become reclusive towards the end of his life, the people of Brighton were reassured by William’s visibility and openness.

However, the Royal Pavilion’s accommodation was not suitable for a married sovereign and extra room had to be found for Queen Adelaide’s extensive household. Further buildings were added to the Pavilion estate, virtually all of which have since been demolished.

Although William and Adelaide continued to entertain at the Royal Pavilion, it was in a much more informal style than the glamour and extravagance of former decades.

Queen Victoria

King William IV died in 1837 and was succeeded on the throne by his niece Victoria.

Queen Victoria made her first visit to the Royal Pavilion in 1837 and this gesture of royal approval thrilled the people of Brighton.

However the lack of space in the Royal Pavilion, and its association with her extravagant and indulgent elder uncle, made Queen Victoria feel uncomfortable. She adopted a policy of financial stringency during her residence in Brighton.

As her family grew and the Royal Pavilion failed to provide her with the space and privacy she needed, she finally sold her uncle’s pleasure palace to the town of Brighton for over £50,000 in 1850. As it was thought the building would be demolished, she ordered the building to be stripped of all its interior decorations, fittings and furnishings, for use in other royal homes.

Town takes over

Brighton continued to prosper in the mid-1800s. The opening of the new London to Brighton railway marked the beginning of mass tourism.

The purchase of the Royal Pavilion was led by Lewis Slight, Clerk to the Town Commissioners. The Town Commissioners were the local authority of the day, and Slight persuade them of the economic and symbolic importance of the former palace.

Within a year of purchase the main ground floor rooms had been completely redecorated in a similar, but much less lavish, style to that of Crace and Jones. The Royal Pavilion was then opened to the public.

By today’s standards Victorian restoration works seemed crude and insensitive. However in the 1890s they were much admired. It was this Victorian civic pride that helped to maintain and secure the Royal Pavilion’s future.

In 1864 Queen Victoria returned many items – chandeliers, wall paintings, fixtures – with further gifts being made in 1899.

From 1851 to the 1920s the admission fee to the Royal Pavilion was sixpence. At this time the Royal Pavilion was also used as a venue for many different events and functions from fetes, bazaars, and shows to balls, exhibitions and conferences. The Royal Pavilion garden was opened up and made accessible to both residents and visitors.

WW1 hospital

In the early months of the First World War, the Royal Pavilion was converted into a military hospital. It was first used for Indian Army soldiers who had become sick or wounded while fighting for the British on the Western Front.

While the men received excellent medical care, the Royal Pavilion hospital was heavily promoted to encourage Indian loyalty to the British Empire. The careful arrangements made to cater for the cultural and religious needs of the patients were widely reported. Great play was also made of the palace’s royal associations, even though the building had been in civic ownership for over 60 years.

After Indian troops were withdrawn from fighting in Europe, the Pavilion was converted into a hospital for British solders who had lost arms and legs through amputation. The hospital for ‘limbless men’ not only provided medial treatment, but also trained the patients in new skills so that they could find employment in civilian life.

The Royal Pavilion remained in use as a hospital until 1920.

Restoring George IV’s vision

During its use as hospital, the Royal Pavilion’s interiors were altered, sometimes damaged, and inevitably neglected.

In 1920 a programme of restoration began, funded by a settlement made by the government for the damage done. This was further boosted when Queen Mary returned original decorations, including furniture that had remained at Buckingham Palace.

After a break during World War II, restoration work began again in earnest with the revival of interest in the Regency era. To ensure that the work was carried out as accurately as possible, every piece of available evidence was examined – from original fragments, drawings and prints to archives and accounts.

The programme of restoration has had occasional setbacks. An arson attack in 1975 badly damaged the Music Room which was then closed for 11 years. Then, in the great storm of 1987, a ball of stone was dislodged from a minaret and fell through the newly restored coving, burying itself in the new carpet. The Royal Pavilion’s conservation team got to work again and the Music Room is now fully restored.

The most recent restoration project has been the Saloon. After years of research and meticulous conservation, the Saloon was returned to its original design in 2018.