Three Extraordinary Lives

During Disability History Month in November, we welcomed Suchitra Chatterjee to the Royal Pavilion to give a talk Three Extraordinary Lives.

Suchitra is a biracial inclusion researcher for Brighton and Hove Black History Group. Following on from the talk, she shares three stories about nineteenth and twentieth century people of colour who had unexpected links with the Royal Pavilion.

Suchitra Chatterjee

Decolonising history, especially the stories of people who are often forgotten, is not easy. The lives of Billy Waters, Tom Wiggins, and Princess Sophia Duleep Singh are no exception.

Although they seem very different, all three had some things in common. All had some African heritage, all were connected to the Royal Pavilion in some way, all played a musical instrument, and all were Disabled people. All were impacted by and part of the British Empire in different ways.

I found myself asking, “How can I decolonise the history of people like Billy, Tom, and Sophia to ensure their stories are respected and given the importance they deserve?”

“We need to look at history carefully, especially when talking about the way in which the British Empire imposed its culture, language, religion, and customs on the people it ruled.”

Billy Waters (1778 – 1823)

Billy Waters was born into enslavement in Georgia, USA. To escape slavery, he volunteered to join the Royal Navy, losing a leg during the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). After leaving the Navy, he was often seen on the streets of London, dancing and singing for money. When arrested for busking, he charmed the judge into letting him go with just a warning or a small fine. It can be assumed that his time in the Navy as a Petty Officer helped him to deal with people from all social classes.

However, two hundred years later, Billy is remembered not for his bravery as a sailor or his efforts to provide for his family, but for his busking on the streets of London.

The pictures of Billy that come up when researching his life can be distressing. George Cruikshank (1792 – 1878) was a cartoonist whose work sometimes seemed to support enslavement, and his print, (an offensive image) “The New Union Club ” shows Billy in this way.

There are also ugly, racist and ableist nineteenth century pottery figures, showing Billy in a torn Naval uniform and hat, playing his fiddle. His features are an exaggerated caricature to match what many people at the time thought a poor, Disabled man of colour looked like. These figurines were popular, and we have this example in Brighton & Hove Museum’s Willetts collection, although it is currently not on display.

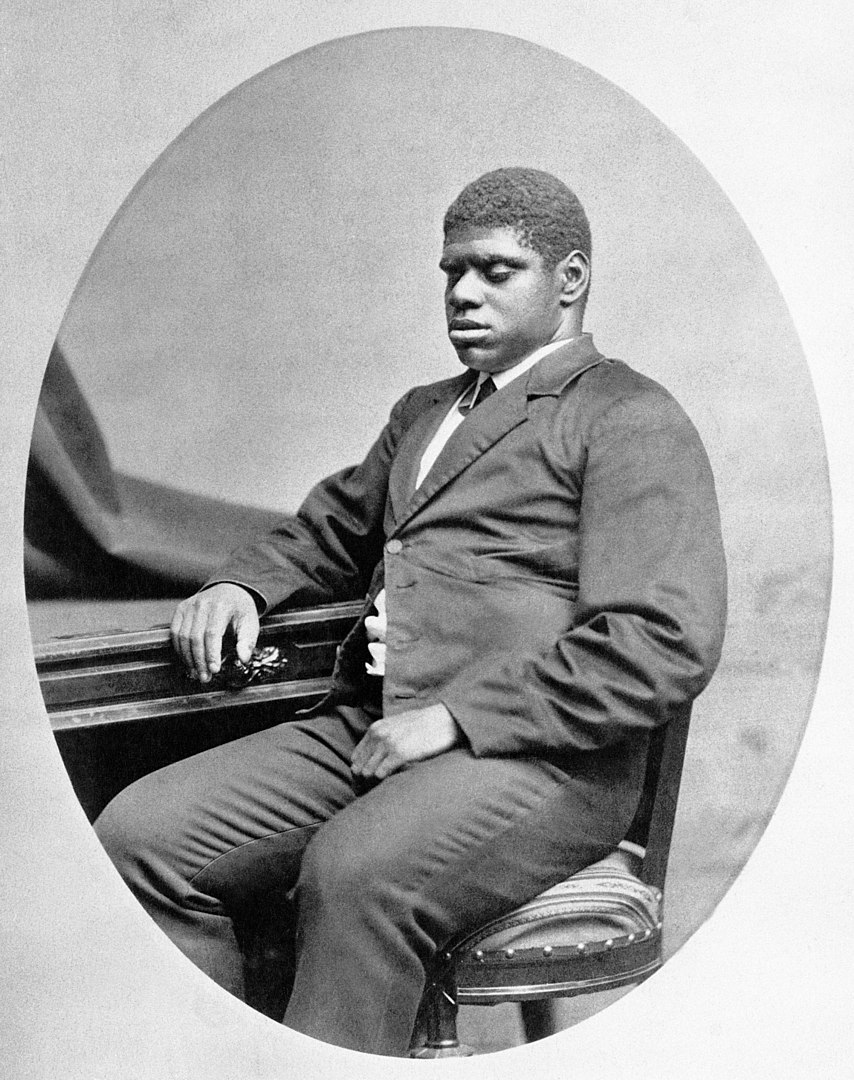

Tom Wiggins (1849 – 1908)

Tom Wiggins had a very different life compared to Billy Waters. Both were African Americans, but Tom was born enslaved, while Billy was born free. Tom was blind and autistic, and became famous for his musical talent as a pianist and composer, making a lot of money for his owner and later his guardians. However, neither he nor his family received much of this money. Even as an adult, Tom never had control over his life or his earnings and became known as “the last American slave”, showing the ongoing injustice of enslavement. Slavery in America was abolished in 1865.

After the American Civil War, Tom’s former owner, General Bethune, convinced Tom’s parents to sign a five-year agreement giving him legal guardianship. This arrangement kept Tom working and making money for Bethune. He was taken on international tours, including two weeks in Brighton during the summer of 1867, where he performed at Brighton Dome and the Royal Pavilion.

Like Billy, Tom faced racial and ableist discrimination. But Tom was mostly protected from the outside world, not out of kindness, but to protect the income he generated for his guardians.

Princess Sophia Duleep Singh (1876 – 1948)

Sophia Duleep Singh was born into a rich and important family, connected to both Indian royalty and British nobility. She lived a life of luxury and privilege in her childhood and was a talented pianist.

At the age of 10, Princess Sophia Duleep Singh caught typhoid fever, a sickness that also claimed the life of her mother, Bamba. This left her with lifelong physical and mental ill health, including chronic fatigue and periods of depression.

Sophia was also a favourite godchild of Queen Victoria. This gave her many special benefits, including protection from the Crown, however this had its limits. When Sophia refused to follow the British Empire’s rules, she faced punishments like threats of house arrest and fines. The British Government watched her closely because of her strong political views around India’s independence and women’s right to vote. She is known for selling copies of The Suffragette newspaper outside Hampton Court Place where she lived in a grace and favour apartment.

During WWI, Sophia volunteered as nurse for the Red Cross. She was rumoured to have helped care for soldiers recovering at the Indian Military Hospital in the Royal Pavilion.

During WWII, Sophia helped Indian sailors called Lascars. These sailors came to England because of British trade. Even though they did important work, they often faced harsh working conditions, were paid less than European sailors, and faced widespread racial discrimination. Sophia helped start the Lascars’ Club in London’s East End. This was a safe place where the sailors could meet, get help, and find resources.

Sophia’s actions demonstrated both her strong sense of social justice, and her desire to help improve the lives of Indian people in Britain. You can listen to an episode of the Empire podcast about her life on Spotify.

Decolonising Historical Narratives

Decolonising history means finding and sharing the stories of people like Billy, Tom, and Sophia. Their stories show how race and disability are an important part of history. They challenge traditional historical accounts, providing a more inclusive and relevant understanding of the past.