The Cat and the Cardinal – A Story from the Royal Pavilion Gardens

This summer, volunteers like myself have been delving into the collections held by Brighton and Hove Museums in order to gain a greater insight into the storied, yet somewhat under-appreciated, history of the Royal Pavilion Garden.

The public events held there after they were opened to the masses, from fêtes to serious public gatherings, are documented in the focus for our recent research efforts – the weighty tomes of newspaper cuttings held in the archives.

The subject of this blog post, however, does not concern these grand occasions. As often remarked about local papers today, and highlighted by social media groups online, they can often be filled with the strangest stories. Surprisingly, this was as much the case nearly 100 years ago. As such, we shall focus in on a wonderful yet tragic local news story, told over a series of articles in the Brighton Herald in the winter of 1923-24.

An article from the 3rd November 1923 is where our story begins. A new visitor has been spotted around the Pavilion gardens – a foreigner from a distant land. Nestling among the evergreens of the Western Lawn among the sparrows, a cardinal has made itself a home in the Royal Pavilion’s gardens.

But, as the Brighton Herald is hasty to add, with a tongue firmly planted in its cheek, “the Cardinal is a not a dignitary of Rome, but of the feathered tribe.” Indeed, a red cardinal with “a crimson head, a white breast, and elsewhere a plumage of grey”, a bird normally native to Americas, had somehow found itself on the south coast of England.

Mystery aside, the colourful new visitor became a smash hit with local people. Visitors to the garden, and the gardeners themselves, took great delight in seeing such an exotic bird in the gardens. Among the gardeners, the cardinal was “looked upon as quite a prized possession”.

On the 24th November, another article appeared. This time it is a letter from one E Hawkins of Prudential Buildings in North Street. Replying to the 3rd November article, his letter explains that his son had brought two red cardinals back with him from South America in June, only for one of them to escape. He seems pleased to hear that this escapee has made a comfortable life for himself out of captivity, writing that “it seems to be quite safe in its present quarters.” Thus, that answers the question of the origin of the Pavilion garden’s newest attraction.

Caws’ and effect

Then, as I continued to flick through the cuttings from the days and weeks that follow, I saw no more of the Pavilion cardinal. What a fun little story, I thought. But as I get into my stride looking at the following year’s articles, tragedy strikes.

From the 2nd February 1924, the piece that caught my eye begins solemnly:

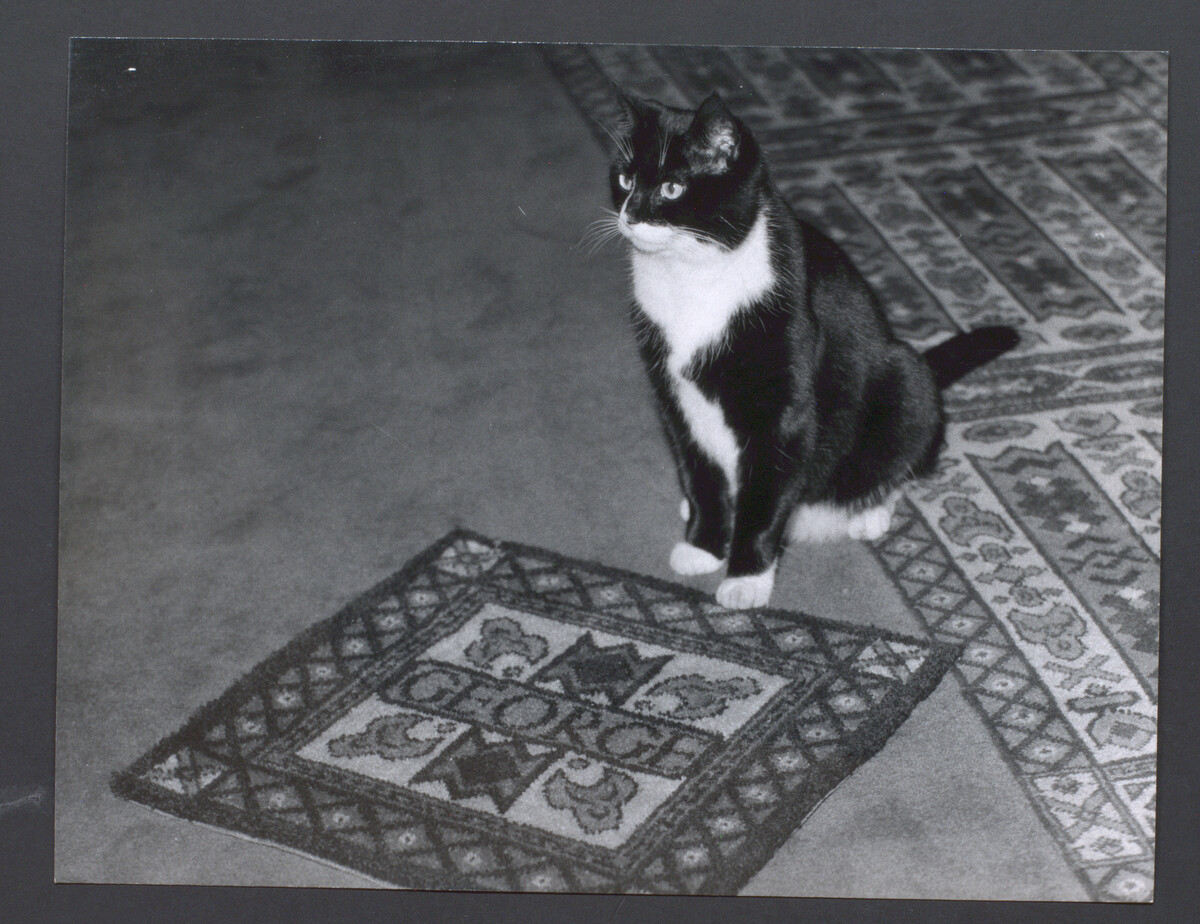

So begins something of an obituary for our unfortunate feathered friend. It recounts his journey, how he’d come to live “like a prince” among the sparrows, and even how he had by some miracle survived the harsh January frost. This all came to an end when he disappeared one day, with “dire suspicion” resting upon the Pavilion cats.

The writer and others seemingly ponder in their mourning that, even when surrounded by sparrows which “teem by the hundred”, it was the cardinal who met its end at the paws of the local felines.

Yet, even with this initial sorrow, flickers of the comedic nature of the first cardinal article still shine through. It is even suggested that the bright colouring of the bird may trigger “learned speculation at the tree tops as to ‘caws’ and effect”, and that the cat may have been “an ultra-Protestant, with an objection to Cardinals.”