History

The Booth Museum was founded in 1874 by naturalist and collector, Edward Thomas Booth. The Victorians were passionate about natural history and Booth’s particular interest was ornithology, the study of birds.

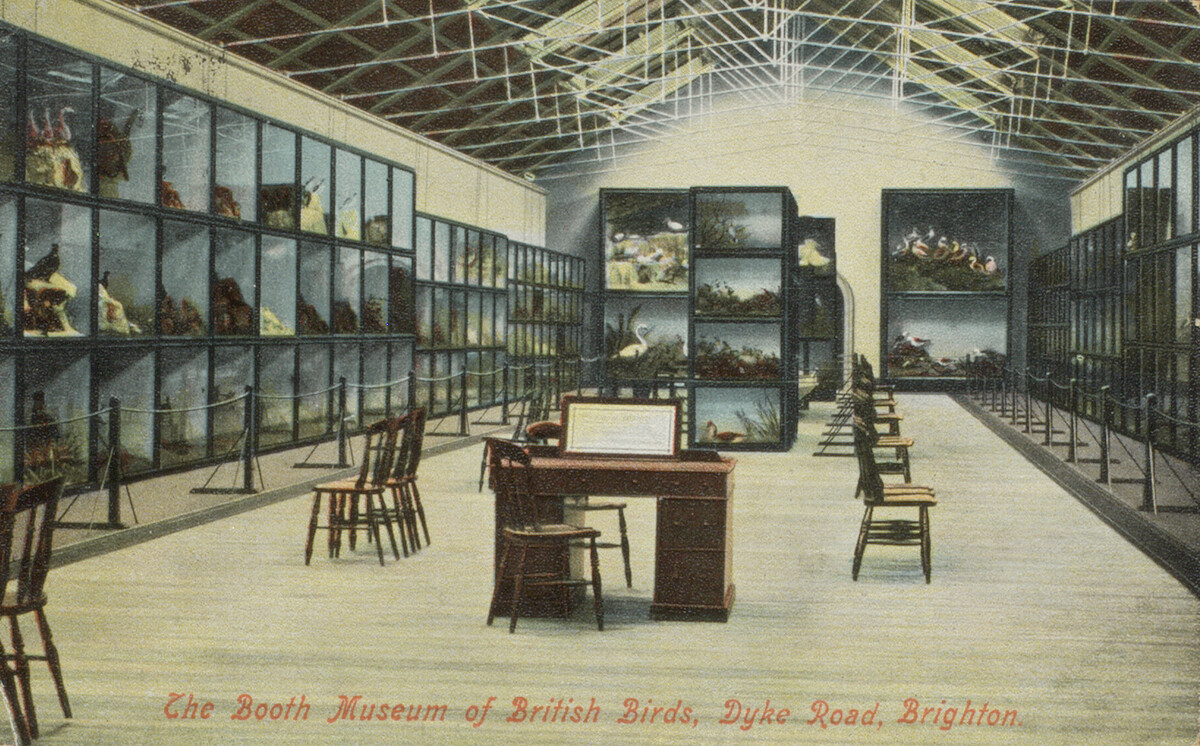

During his lifetime he collected a huge variety of stuffed British birds and was a pioneer of the environmental type of display called ‘diorama’, displaying birds in their natural habitat. It was this collection of over 300 cases (with the proviso that the dioramas should not altered) that launched the opening of the museum under Brighton civic ownership in 1891.

The collection grows

In 1971 the Booth became a Museum of Natural History. It is now home to a staggering collection of 525,000 insects, 50,000 minerals and rocks, 30,000 plants and 5,000 microscopic slides. There are some spectacularly old specimens such as shells from the bottom of a 55 million year old Mediterranean lagoon, and dinosaur bones.

The museum retains its unique charm of the quirky and eccentric with its focus on Victorian taxidermy and fossils, bones and skeletons. And yet it is also firmly focused on modern day concerns of conservation and protection of the planet.

Temporary exhibitions and year-round family and school activities help to promote awareness and understanding of the natural world in a fun and stimulating way.

Who was Mr Booth?

Booth was born in Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire, on 2 June 1840. He was the only child of Edward Booth, a gentleman of independent means and his mother Marianne who was one of the well-known Beaumont family of Northumberland. By 1850 the family had moved to Hastings, Sussex, where the young Booth was taught taxidermy by Kent, the bird stuffer and barber from St Leonards. Presumably his lifelong enthusiasm for wildlife and hunting started at this stage of his life.

In 1854 the family moved to Vernon Place, Brighton, where he attended a private school. He went on to Harrow and finally to Trinity College Cambridge from where he was sent down — probably for working harder at shooting on the Fens than on his actual studies.

Booth’s early hunting started in the marshes near Rye, increasing his range in later life to the Norfolk Broads and the Scottish Highlands. With the first Mrs Booth he moved to Dyke Road, Brighton, where he had built their home called Bleak House and in 1874 he built his museum in the grounds. At this stage the Booth Museum of British Birds was not open to the public, which occurred gradually with charitable fundraising events. By then he had formulated his ambition to exhibit one example of every species and recognisable stage of British bird, all of which he had collected, and set about the task of building up his collection.

Booth published his Rough Notes, three volumes of coffee table sized books, which amply demonstrate his detailed knowledge and powers of observation. He employed Edward Neale, a little known artist, who based all of his illustrations on specimens in the Booth Museum.

Booth’s diaries, most of which still exist and form the basis of the text of his book, are largely rather dry accounts of shooting expeditions and include frighteningly large lists and tallies of creatures shot. He certainly was an excellent marksman.

Here and there however it is possible to glimpse behind the rifle sights into the character of this very private man. A man whose dog’s names are recorded but not his wife’s, who shoots at another gunner who had the temerity to come too close when shooting on the Norfolk Broads, who enjoyed whiskey, Cross & Blackwell’s tinned soup and the company of ghillies (wardens hired to chase away poachers).

Rumours about Booth include keeping a locomotive under steam for an entire week to enable him to leap into a hot train and travel to Scotland on receiving word from the ghillies who were searching for examples of the few remaining White-tailed Eagles. Also that he raised fledgling gannets in pens behind his house to enable him to kill them when they reached the level of plumage required for his display. Even that he became increasingly eccentric, even alcoholic, and fired his shotguns at the postmen on Dyke Road.

At some stage we do know that Mrs Booth became ill and died. Her nurse, Bessie, became his second wife. He himself died on 2 February 1890 and was buried in Hastings cemetery. Shortly after his death the young widow donated his gun collection to the museum. Mrs Booth also commissioned a fine Portland stone pulpit inscribed to his memory to be erected at St Andrews Church, Portslade. The inscribed stone was given to the Booth Museum when the church was decommissioned. Booth’s original hope was to bequeath his museum to the London Museum of Natural History; they persuaded him otherwise. Brighton Corporation, as it was then called, became the beneficiary and there it has remained ever since.