This is a legacy story from an earlier version of our website. It may contain some formatting issues and broken links.

In today’s 100 Pioneering Women of Sussex blog curator Alexandra Loske shines a light on a Sussex woman who wrote a fine book on the beautiful city of Florence in the early 20th century, and the works of art she donated to the museums of Brighton and Hove.

Some of the pioneering women authors I have been writing about in lockdown have been more visible and publicly known than others. The most famous one, Jane Austen, hardly needs an introduction, but when looking at the history of women, it is important to research and tell the stories of those who did not have the same exposure. Mary Lloyd was one of those whose life I tried to trace in the last few months, as is Clarissa Goff.

Clarissa Catherine Goff was born into undoubtedly privileged circumstances, but this didn’t open up the world of formal and higher education to her. Like most women in the late 19th century, she was not able to go to University or pursue a professional career. She was born in 1862 to Arthur John de Hochepied Larpent, a Sussex baron, and Catherine Mary Melville, who was born and died in India. Clarissa lost her mother at only 12 years of age, and possibly travelled to India as a child, along with her six siblings.

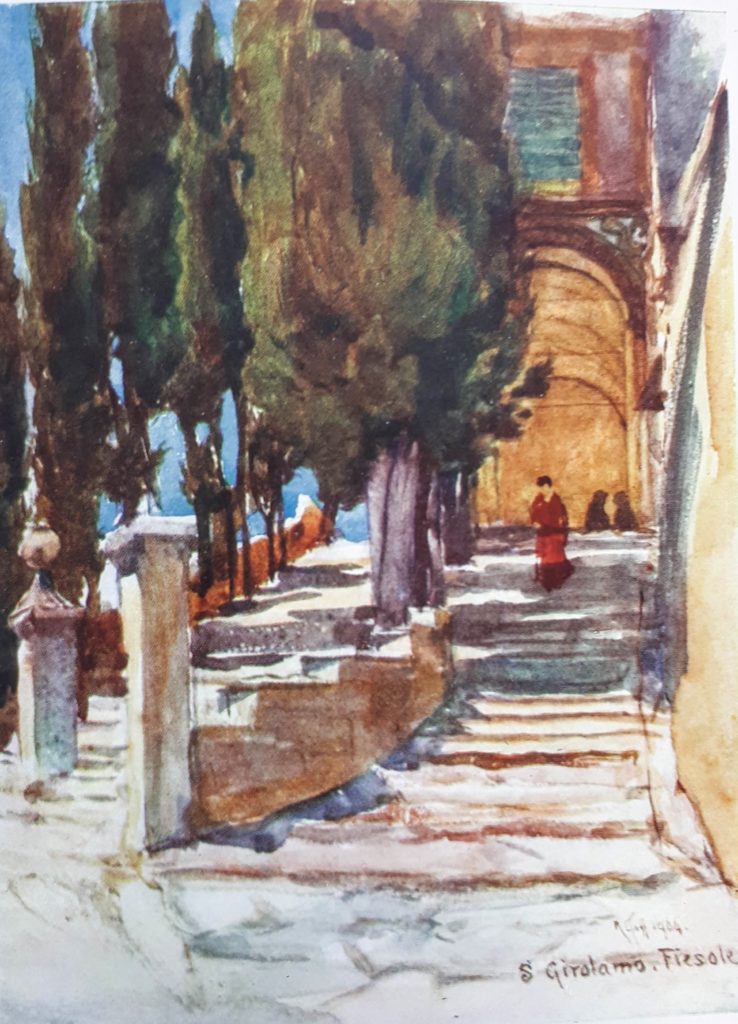

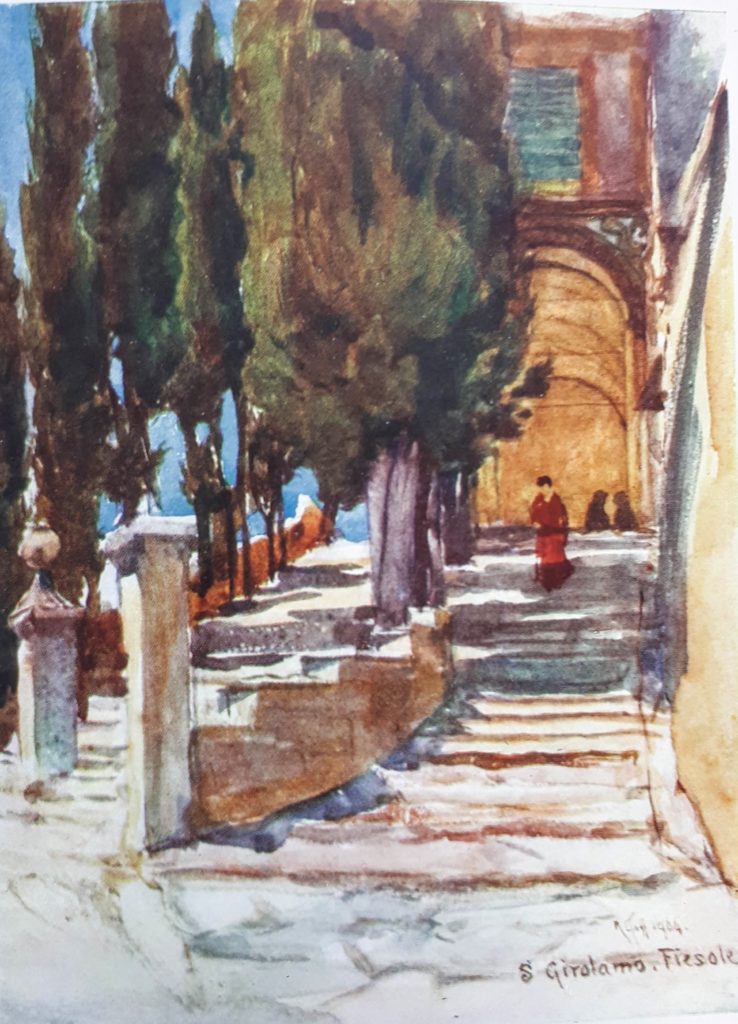

San Girolamo, Fiesole, from Clarissa and Robert Goff’s Florence & some Tuscan Cities (1905)

In 1899, aged 37, she married Robert Charles Goff (1837–1922) in Kensington, London, and has until now only been discussed in connection with her husband. Robert Goff had been a professional soldier and joined the Queen’s Own before he was 18, fighting in the Crimea. He later exchanged to the Coldstream Guards and became an honorary Colonel in the early 1870s. He retired from the army in 1878, and married Beatrice Teresa Testaferrata-Abels, of Maltese nobility, the same year. They settled in London for a while, before spending long periods in Hove, Italy and Switzerland. Goff and his first wife moved into a large house on the east side of Adelaide Crescent in Hove in or around 1889. They had one son, Francis, who died young, and Beatrice herself died in 1896, while travelling in Scotland.

Hotel Metropole, c1895, by Robert Goff

Goff emerged in the early 1870s as a highly accomplished etcher and within a few years carved out what was to become a long, assured and very productive career as an artist. He was elected a fellow of the newly established Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers in 1887, was a member of the Arts Club, London, from 1871 to 1891 as well as an honourary member of the academies of Milan and Florence. He regularly exhibited at the Royal Academy and several other important institutions and galleries. In Brighton he was a member of the Fine Arts Sub-Committee for many years, assisting in the selection of pictures for various exhibitions, as well as making generous donations to our collection.

Holland Road, 1912, etching by Robert Goff.

So Clarissa married a man who was several decades older than her and had recently lost his small family, but who was happy to pursue a new career in the arts in his retirement. They had no children, but it seems that they were happy devoting their lives to travelling and supporting museums, galleries and academies in England and abroad. They left the large house in Adelaide Crescent in 1903 to move to Italy, but kept a studio in Holland Road until Robert Goff’s death in 1922. This studio was probably purpose-built for Goff in the 1890s. It was a white, double-gabled house that backed onto his home in Adelaide Crescent and was connected to it via some steps which are still there today. In this studio there was probably had a small printing press where he produced many of his etchings. Incidentally, I was recently contacted by the current owners of that house and was able to look for signs left by the Goffs.

The Goffs settled in Florence after they left Hove and spent at least a decade there. Their house, the Villa dell’Ombrellino, stood on the top of a hill, offering grand views of the city. Shortly after they arrived in Tuscany, Clarissa and her husband embarked on a collaborative project, a book entitled Florence & Some Tuscan Cities. It was published in 1905 by A&C Black in the popular 20 shilling series of topographical books with many colour illustrations, intended to be given as gifts, especially at Christmas. Books of this type made use of advances in photographic colour print reproduction, and buyers were encouraged to collect volumes of each series. The covers usually boasted elaborate gilt and pictorial designs, heavily influenced by the Aesthetic movement. Many of the volumes were illustrated by well-known artists and etchers of the time, such as Mortimer Menpes, Wilfrid Ball and William Wyllie. The Goffs’ Florence book includes reproductions of 75 watercolours by Robert, many of which were later turned into etchings.

The cover of Clarissa and Robert Goff’s Florence & some Tuscan Cities (1905)

While most artists who illustrated these gift books were men, a surprising number of the books were written by women, in many cases wives, sisters or daughters of the artists. Writing in a descriptive and evocative way about art, culture and history was for many late-19th and early-20th century women the only socially acceptable way to be published.

While higher education was still out of bounds for most women, a significant number of women could at least read widely, visit galleries, keep travel diaries, and acquire some level of knowledge and expertise through careful observation. A couple of generations earlier, Mary Philadelphia Merrifield, about whom I wrote in an earlier blogpost, used empirical and observational methods to produce her work on colour and artists’ techniques, despite not having been formally trained or educated. A surprising number of gallery and travel guides from the late Victorian and Edwardian Age were written by women and have only recently been recognised and researched. These women were not always credited as authors. They or their publishers sometimes used abbreviated first names or pseudonyms, but once you know what to look for, you will find a huge range of fascinating non-scholarly books on the arts, history and sciences, written by women in that period. I am currently working my way through guides of some of the greatest art galleries in the world, including London’s National Gallery, the Pitti Palace and the Dresden Art Gallery, written by Julia de Wolf Addison, published around the same time as the Goffs’ book on Florence.

Many of these books are well-written and combine personal anecdotes and reactions with detailed descriptions of the subjects. This makes for accessible and highly enjoyable reading. Clarissa Goff was particularly skilled at creating the atmosphere of a place through a personal memory, before moving on to accurate descriptions of architecture or art. Her chapter on Pisa, for example, begins with an impression connected with the scent of orange blossom: ‘On a certain sunny May-day, when, after long years, we were renewing acquaintance with the dreamy old city, the perfume of orange flowers met us as we entered the streets. It was floating everywhere on the still air. Through the quaint white thoroughfares, in which the grass pushed its way unchecked between the paving-stones, each high garden wall was overtopped by the burnished green leaves of orange trees, starred with multitudes of small creamy flowers. Their sweet scent accompanied us on our way…’. Clarissa Goff paints a picture of a Tuscan town in early summer with words here, a perfect companion to her husband’s watercolours. If this does not make you want to go travelling right now, after months of Covid-19 lockdown, I don’t know what will.

Publications like these are largely excluded from the academic canon and considered simply popular, dispensable literature. We should perhaps now realise that they are invaluable as reflections of their time and an expression of women’s creativity within the restrictions of their circumstances. I pick up these books whenever I spot them in second-hand bookshops and charity shops. Some of the rarer ones you may have to search for online, such as de Wolf’s guide to the Boston Museum of Arts from 1910. We must not forget that the women who did manage to travel, write, and publish in Goff’s lifetime were doing it in privileged circumstances compared to the majority of other women, but it was at least a beginning of women paving a way into writing, publishing, and eventually higher education and greater independence.

Admittedly, I only came across Clarissa Goff’s book through her husband’s work. Around 10 years ago I bought some of his etchings in an antique shop in Lewes and began to research him. I was astonished to find that there are hundreds of his etchings, as well as some watercolours and lithographs in our collection, many of them in multiple impressions and versions. They form an fascinating insight into the art of etching, and led to my first curated exhibition at Brighton Museum, in 2011. It turned out that we have Clarissa Goff to thank for this rich collection. After Robert Goff died in Switzerland in 1922, she donated the contents of his Hove studio to Brighton Museum & Art Gallery (then divided into Brighton and Hove). Among this treasure trove of images are many of the etchings and some of the watercolours that formed part of their book on Florence.

Selecting Goff’s works for the exhibition in 2011. Everything seen here was donated by Clarissa Goff.

Clarissa and Robert Goff collaborated on another book, Assisi of Saint Francis, in 1908. Clarissa died in the 1930s, but I have yet to find her grave. There are some pictures of Clarissa, but none that we can reproduce here. Part of me wants her to be the woman in red on the steps of the convent of San Girolamo on a hot summer’s day, in one of the plates in the book (seen at the top of this blog). She was painted at least twice by George Percy Jacomb-Hood, a fellow-etcher who was a good friend of the Goffs and also her brother-in-law. They were painted in Tite Street, London, not far from the houses of James McNeill Whistler, John Singer-Sargent and Oscar Wilde. You can see the picture here. If you happen to see her book on Florence anywhere cheaply, do snap it up. It provides perfect armchair travel in these strange times, and perhaps one day soon we can travel again easily and retrace the Goffs’ steps in Tuscany.

Alexandra Loske, Curator, The Royal Pavilion