This is a legacy story from an earlier version of our website. It may contain some formatting issues and broken links.

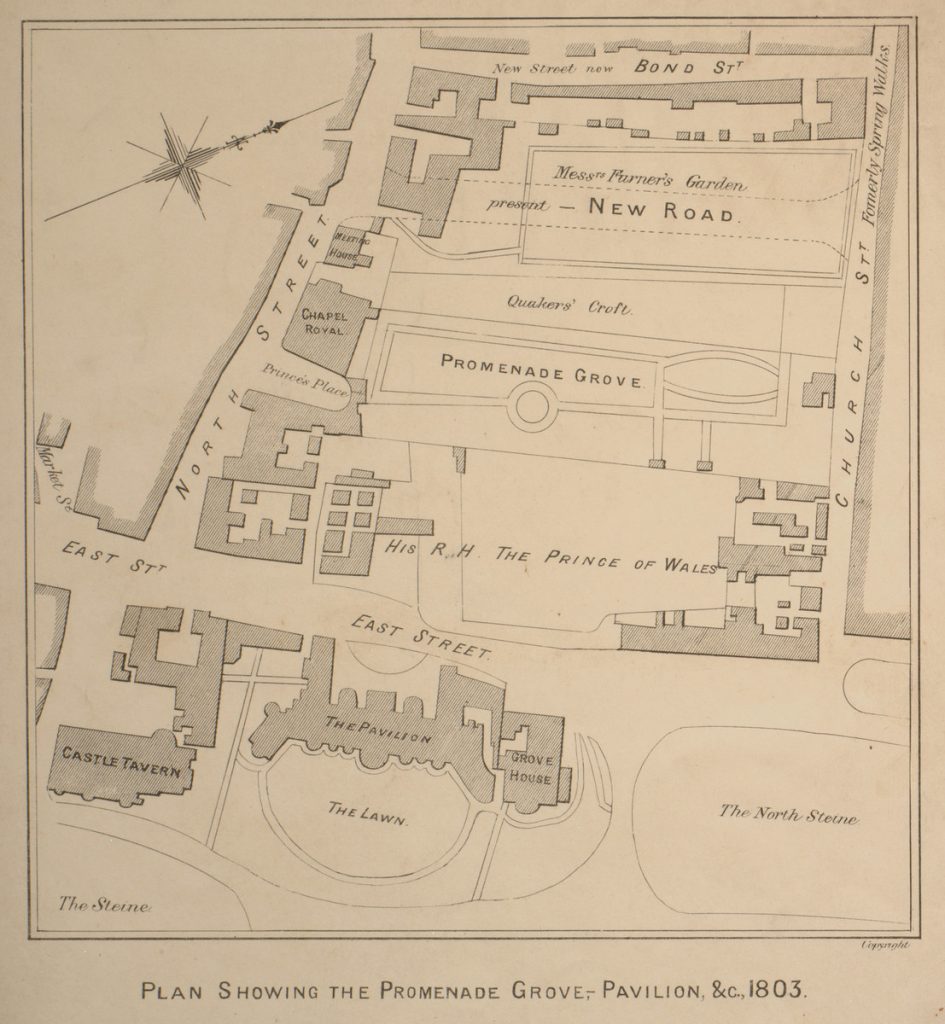

Today marks the 200th anniversary of the death of Jane Austen. To commemorate the event we have created a new temporary display, Jane Austen by the Sea, which can be seen in the Prince Regent Gallery in the Royal Pavilion. It explores the great novelist’s relationship with the seaside, sea-bathing and the Prince Regent.

Among the exhibits is a print I particularly like. It is an image of a man of Indian origin, dressed in what appears to be Indian clothing, standing against an imagined landscape that combines a seascape, a garden and a building with minarets and a dome. The building is reminiscent of both the Royal Pavilion and images created by Thomas and William Daniell. The Daniells were two artists who travelled through India in the 1780s and 90s, and subsequently painted images of India for a Western audience who were keen to see pictures of the unfamiliar East.

The man in the print is entrepreneur Sake Dean Mahomed, one of the best known early Asian immigrants to Britain. He was born in 1759 in Patna, North-eastern India, and later joined the Native Infantry of the East India Company. After a successful military career, he moved to Ireland in 1784 where he studied English and fell in love with an Irish woman whom he later married. He published a book in English about his travels in 1794 and moved to London with his family in 1807. There he opened a Hindoostane Coffee House, and introduced Indian cuisine to the English palate. He later became a professional ‘shampooer’ in Brighton, where he opened Mahomed’s Baths near the seafront in 1812. His business was described in advertisements as:

‘The Indian Medicated Vapour Bath, a cure to many diseases and giving full relief when everything fails; particularly Rheumatic and paralytic, gout, stiff joints, old sprains, lame legs, aches and pains in the joints’.

He eventually became ‘shampooing surgeon’ to George IV and William IV.

The print, a lithograph by Thomas Mann Baynes and printed by Charles Joseph Hullmandel, is one of many images of the illustrious Sake Dean Mahomed. It is a testament to both Georgian society’s continued fascination with the East, and a personal respect for Mahomed. The dress he is wearing in this picture was a cultural hybrid, probably invented by Mahomed himself and worn at court, with the intention of looking both exotic and modern, combining Eastern and Western features. Under the thigh-length, long-sleeved silk coat in the style of Indian court dress, for example, he wears a pair of tailored long breeches that are in fact a very early pair of trousers. Astonishingly, Mahomed’s extraordinary outfit survives in our collection, and we have displayed it alongside the print in the Jane Austen exhibition. Even his red leather shoes survive, but because the outfit is on open display we have not been able to include these. A large portrait of Mahomed, in Western dress, can be seen in the history galleries of Brighton Museum.

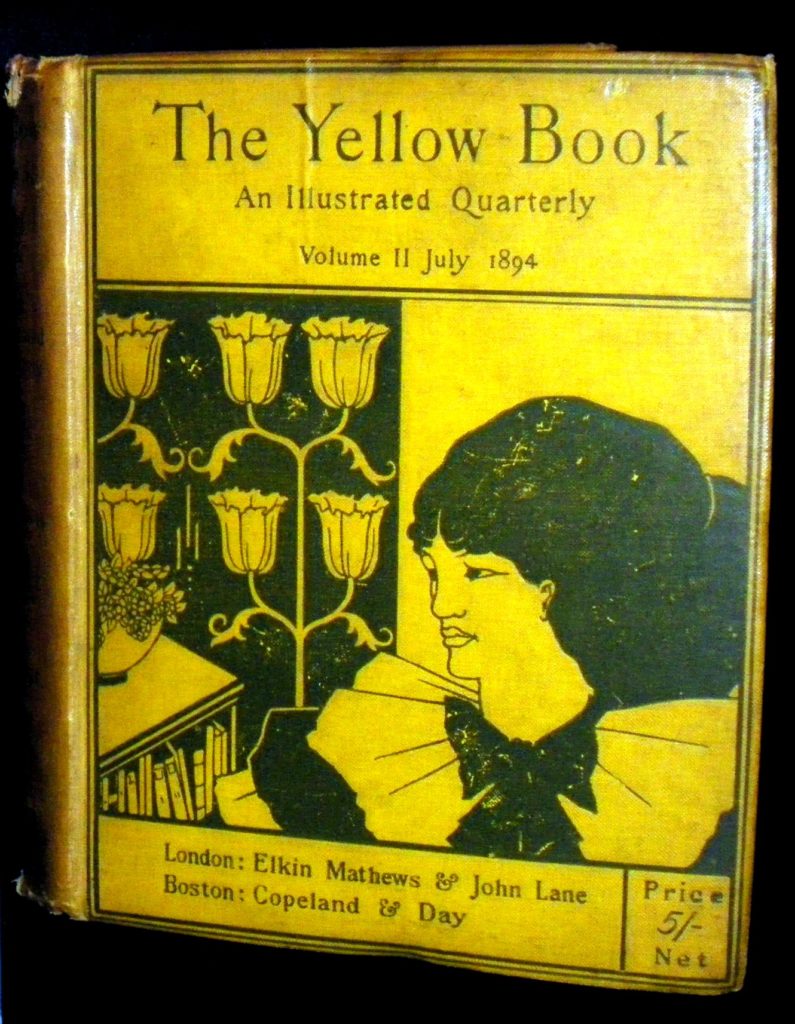

And what about Jane Austen ‘taking the waters’ or ‘being dipped’? We know that she loved the sea and frequently visited seaside resorts, among them Sidmouth, Dawlish, Colyton, Teignmouth, Charmouth and Lyme Regis. We cannot be sure that she ever visited Brighton, but it is likely that she knew about the town through the reports of her brother Henry, who was stationed here and nearby in the 1790s, while serving in the Oxfordshire militia. Both the seaside in general and Brighton in particular were a great inspiration for Austen’s work and fashionable ‘watering places’ feature in novels like Pride and Prejudice, Persuasion, Mansfield Park and her last, unfinished, novel Sanditon. A manuscript of Sanditon, in her sister Cassandra’s hand, is on display in our exhibition, on loan from Jane Austen’s House Museum in Chawton.

Despite enjoying the seaside, Austen never learnt to swim. Like many seaside visitors she relied on the help of a ‘dipper’, a strong person who would lower you into the shallow water, usually from the steps of a bathing machine that had been pulled into the sea by a donkey. In 1804 Austen caught a fever while staying in Lyme and decided to take to the bathing machines. She wrote to Cassandra, who was in Weymouth at the time: ‘I continue quite well, in proof of which I have bathed again this morning.’ At times she even seems to have overindulged in dipping and sea-bathing. She reports in another letter:

‘The bathing was so delightful this morning and Molly [probably her dipper] so pressing me to enjoy myself that I staid in rather too long, as since the middle of the day I have felt unreasonably tired. I shall be more careful tomorrow, as I had before intended.’

Alexandra Loske, Curator of Jane Austen by the Sea.

Jane Austen by the Sea forms part of our Regency Season in 2017, which will also include the exhibition Constable and Brighton, and the display Visions of the Royal Pavilion Estate (both at Brighton Museum & Art Gallery).

A version of this article was previously published in the June 2017 issue of Viva Brighton Magazine.