This is a legacy story from an earlier version of our website. It may contain some formatting issues and broken links.

A rare view of the Pavilion by one of Britain’s greatest artists

This exquisite watercolour by JMW Turner entered the collection of Brighton Museum & Art Gallery only a few years ago. It had been in private collections since it was bought in the 1830s, and came up at an auction in New York in 2012. We were able to purchase it with generous help from the Art Fund, the Heritage Lottery Fund and private patrons.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, R.A., Brighthelmston, Sussex, c1824 © The Royal Pavilion & Museums. Pencil, pen and black ink and watercolour with scratching out on Whatman paper. 14.6 x 22.2 cm

It was of utmost importance to secure this gem, as it is one of the few paintings by Turner that shows the Royal Pavilion. The palace is only faintly visible in the oil painting Brighton from the Sea (1829), which was commissioned by one of Turner’s patrons, George Wyndham, 3rd Earl of Egremont, at Petworth House, and in a few other rough sketches in pencil and watercolour, for example in this sketchbook from 1830. In our watercolour Turner took a few compositional liberties for the sake of the ‘picturesque’ appeal of the image, for example turning the Pavilion by about 90 degrees to ensure the whole of its east front can be seen.

Compared to other paintings of Brighton by Turner our watercolour provides a surprising amount of detail. Many buildings of Brighton can be identified, among them St Nicholas’s Church, the Duke of York’s hotel, and Marine Parade under construction. The most prominent building is the recently finished Chain Pier, a bold cast-iron structure that seems to be withstanding strong waves and stormy conditions and is gleaming in the sunlight. It pushes its way into the composition with all the pride and confidence we see a few years later in other great cast iron structures, such as railway bridges and stations.

The reason for this detailed rendering and the painting’s relatively small size is that it was meant to be engraved. The printed version was used as an illustration in Picturesque Views of the Southern Coast of England, an important topographical publication by George and William Cooke. It was published in 16 parts between 1814 and 1826, with Turner contributing a total of 39 images. George Cooke engraved the watercolour and entitled it Brighthelmstone, Sussex, using the old name for Brighton.

While the apparent subject of the painting are bustling Brighton and the Chain Pier, something else shapes this image and demands attention: the sea, the sky, and the stormy and quickly changing weather conditions of the scene. Water in many shapes and forms plays an important role in Turner’s work. A large proportion of his paintings depict the sea, rainstorms, cloud formations, waterfalls, rivers, mist, snow and floods. Like many artists and scientists of his time Turner was an observer of nature, atmospheric conditions and meteorological studies, frequently sketches outdoors, ‘en plein air’, attempting to capture fleeting moments with great immediacy. Our watercolour is a prime example of aesthetic ideas of the ‘picturesque’ which had its roots in the 18th century but prevailed in the early 19th century. The concept of the picturesque was to combine two earlier and seemingly jarring aesthetic concepts, that of ideal ‘beauty’ and of the ‘sublime’. In the 1750s writers, artist and thinkers such as Edmund Burke and William Hogarth had argued that beauty was to be associated with purity, symmetry, order and pleasing lines, while the sublime was the unknowable, dangerous, chaotic and awe-inspiring. In the visual arts you see manifestations of the sublime in depictions of, for example, vast mountain ranges, natural disasters such as floods and storms, while ideal beauty may be associated with classical aesthetics, especially in architecture. By the 1770s writers began to combine these two concepts, resulting in aesthetic ideas about ‘the picturesque’, which could be applied to many areas of life and the arts, but were largely associated with travel, illustration, fine art, poetry, and garden design.

One of the great advocates of picturesque landscape gardening and architecture was Humphry Repton, who proposed new designs for the entire Royal Pavilion estate in 1806, which were, sadly, never executed. In his last publication before his death in 1818, Fragments on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (published in 1816) Repton elaborated on some of his ideas concerning the picturesque and colour, and used the rainbow spectrum and ever-changing light conditions to explain his theories. We have one of the plates from this publication in our collection. It merges Newton’s early 18th century findings concerning optics with early 19th century colour theory and picturesque aesthetics. (There is a chance to see Repton’s discarded designs for the Royal Pavilion at this talk at The Keep on 11 May: http://www.thekeep.info/events/early-illustrated-books-of-the-royal-pavilion-and-other-royal-palaces-a-talk-by-dr-alexandra-loske-3-00-admission/ )

A wealth of publications in the late 18th century advised readers on how to travel and appreciate your surrounding in a picturesque manner, for example William Gilpin’s Three Essays: On Picturesque Beauty; On Picturesque Travel; and on Sketching Landscape: to which is Added a Poem, On Landscape Painting, published in London in 1792 but based on his travels in the 1760s and 1770s. Images, gardens and buildings in a picturesque manner would embrace irregularity, ruggedness and imperfections, but still aimed to be pleasing compositions, while sublime aspects could still be included, in the form of dramatic landscapes, vast scenery or wild weather conditions. Crucially, picturesque ideology encouraged considering the British countryside as valuable and worthy of study as going on a ‘Grand Tour’ with Rome as a destination. A perfect picturesque image would be well observed and carefully composed, but contain elements of surprise and tantalising details that would trigger curiosity, such as ruins, old trees or interesting rock formations. This is one of the reasons why Turner depicted Brighton not just with all its exciting new buildings and structures,but also in dramatic and quickly changing atmospheric conditions. The insertion of a rainbow on the left side of the painting highlights the contrast between dark and clear skies, gives it a fleeting feeling and an immediacy that he perhaps associated with Brighton. While severe storms are recorded in Brighton in 1824, it is unlikely that Turner wanted to document an actual storm. It is much more likely that he included high waves, large cloud formations and indeed a rainbow to give the image a picturesque quality, with more than a slight hint of the sublime. Depicting Brighton in 1824 in a book entitled Picturesque Views of the Southern Coast of England had to be more than simply showing a pretty beach and some exciting architectural structures, and Turner delivered.

The prints based on the watercolour were also published individually and it is still relatively easy to find a later print of the engraving, as it remained popular and was reprinted and copied throughout the 19th century. The watercolour however disappeared from public view until it was first shown at Brighton Museum shortly after it had been purchased by us. In 2013/14 it was the star of an exhibition in the Royal Pavilion on Turner and his relationship with Brighton, curated by Turner expert Ian Warrell. Because it is a watercolour the painting cannot be exposed to light for very long and is therefore not permanently on display, but we occasionally offer gallery talks during which it can be viewed. The shimmering painting is in demand: in 2017 it will be lent to an exhibition at the Frick Collection in New York, thus briefly returning to where it appeared at auction in 2012.

A shorter version of this article was published in the May 2016 issue of Viva Brighton magazine

Dr Alexandra Loske, Art Historian and Curator at the Royal Pavilion

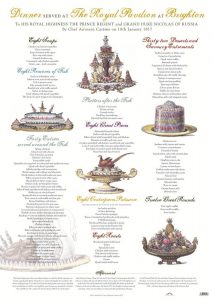

On 19 July 1928 workers carrying out road excavations in Wild Park, Brighton, found a human skeleton. The find was reported in the Sussex Daily News as being that of an elderly prehistoric person, probably female, found lying on their left side, facing north-east with their knees slightly drawn up, about 4 feet (1.2 metres) below the ground surface. No grave goods or other artefacts were found with the skeleton. The burial was located next to a saucer-shaped pit, thought to perhaps have been the hearth from the floor of a prehistoric hut.

On 19 July 1928 workers carrying out road excavations in Wild Park, Brighton, found a human skeleton. The find was reported in the Sussex Daily News as being that of an elderly prehistoric person, probably female, found lying on their left side, facing north-east with their knees slightly drawn up, about 4 feet (1.2 metres) below the ground surface. No grave goods or other artefacts were found with the skeleton. The burial was located next to a saucer-shaped pit, thought to perhaps have been the hearth from the floor of a prehistoric hut.