This is a legacy story from an earlier version of our website. It may contain some formatting issues and broken links.

Paula Wrightson celebrates the 2018 Chinese Year of the Dog by investigating the story of Kylin, Ellen Thomas-Stanford’s Pekingese through the breed’s origins in Imperial China, to links with the Opium Wars and the sinking of Titanic.

There are two oil painting portraits of Pekingese dogs on display at Preston Manor: Chu-Ki and Ellen’s beloved Kylin. The breed is native to China and until the 1860s found only in the closed confines of the Imperial palaces of the Chinese Emperors where the breed was celebrated as the Lion Dog. By 1900 the Pekingese was still relatively new to Europe so how did Kylin, born in 1909 come to be resident at Preston Manor?

Kylin: Faithful and Fearless (1909-1924)

Kylin. Oil painting by Arthur John Elsley, 1917

Kylin and kitchen cats

Kylin arrived at Preston Manor as a puppy and in respect of her aristocratic origins she immediately acquired the position of top dog. If Ellen Thomas-Stanford was the Lady of the House, then Kylin was surely her equal in animal form. Ellen was a keen photographer and Kylin became her frequent subject cropping up in the most unexpected images including a playful scene in the kitchen garden. Kylin stares at the camera aside two startled tabby cats, one clinging to the bare branches of a small tree. Here we can judge Kylin’s size, which is about that of an ordinary domestic cat. In Imperial China the smallest Pekingese were prized and termed ‘sleeve dogs’ by the British when seen carried in the sleeve of a Chinese robe.

Along with the oil painting we are left with a charming pen-portrait of Kylin written by Marjory Roberts, daughter of Preston Manor’s first curator, Henry Roberts. In an article for the Sussex Daily News dated 26 March 1935 The Companionship of Dogs Marjory recalls the animal she knew:

‘Kylin was Lady Thomas-Stanford’s Pekingese and her favourite…she was a delightful pet and full of endearing ways. The picture shows Kylin in a characteristic pose, guarding a dog biscuit. This sometimes took the part of a game, played for preference in the hall with its polished oak floor. Suddenly she would throw the biscuit up in the air, watch it go the length of the hall, then tear after it, put one paw on it, and skid along the slippery floor. When she came to a standstill she would guard it again and so start the game afresh.’

Marjory ends in an anthropomorphic vein,

‘She would make few human friends but loved the companionship of other dogs. Jock and she were often together and one day a photograph was taken of them sitting on top of the mounting block in front of the house. This is an excellent likeness of them both, particularly showing the essential kindliness of Jock’s face and the pride on Kylin’s. The photograph was used many times on the cover of menu cards for Preston Manor.’

Jock and Kylin

“One she couldn’t sell”

In 2008 a Pekingese expert, Sarah Cheang, visited Preston Manor and, examining the Elsley portrait, gave her verdict on Kylin as an example of the breed,

‘Looking at the picture I would say Kylin was not the sort of Peke that wins prizes – in other words Kylin was not very true to form and would not have scored many points when judged against the standard…’

Ms Cheang comments on Kylin’s ‘very spanielly appearance’ stating that many early Pekes imported into Britain were probably Tibetan spaniels, a breed not recognised by the Kennel Club until 1902.

Accepted for Kennel Club registration in 1910, the Pekingese became the fashionable toy-dog breed of the Edwardian period. By 1912 it had replaced the Pomeranian in popularity. Kylin was bred within a socially exclusive circle of Pekingese enthusiasts whose ranks included Ellen’s daughter-in-law, Evelyn Benett-Stanford, wife to her son John. Kylin came to Preston Manor as a gift from Evelyn – but Kylin’s lack of pedigree appearance mark her as the reject of the litter.

Evelyn Benett-Stanford, 1911

One wonders what might have happened to the unwanted pup if Ellen hadn’t taken her in. Evelyn was a no-nonsense strong-minded and unconventional individual pictured here looking ill at ease in a white gown and black hat and with her customary monocle. A fearless woman, Evelyn took part in the early motorcar rallies on Brighton seafront, when she wasn’t shooting big game in Africa.

‘Probably Mrs Benett-Stanford gave Ellen one she couldn’t sell!’ writes Ms Cheang of the puppy although she adds, ‘Kylin is certain to be one of those early Pekes,’ and this fact is rather exciting when considering Kylin’s Chinese origins.

A chance find in a charity shop

In researching Preston Manor’s human occupants, I often look at family trees, so when browsing in a charity shop and finding a copy of the Pekingese Scrapbook (1954) by Elsa and Ellic Howe I was thrilled to see a family tree titled, ‘Important Early Pekingese.’ This invaluable document, though not showing Kylin, helps unpick her ancestry via a character already known to Preston Manor: Thomas Douglas Murra,y who was Evelyn’s uncle by marriage. He appears on the tree as an early importer along with names acclaimed in the exclusive world of late Victorian Pekingese breeding: Loftus Allen and Gordon-Lennox.

The Pekingese Scrapbook & Important Early Pekingese family tree

The Curse of the Mummy and the sinking of Titanic

Murray (1841-1911) is described in the book as ‘a man of means and widely travelled’. He was a fascinating character, a member of the famous Ghost Club who attended séances at Preston Manor in the 1890s conducted by his associate, the renowned medium Ada Goodrich Freer. In his youth, after graduating from Oxford, Murray explored Egypt and had the misfortune to buy the sarcophagus of the priestess Amen-Ra, an object reputed to be cursed.

Indeed, in Egypt he lost an arm to gangrene after a shooting accident – and further bad luck followed within his travelling circle. In 1912 the so-called ‘cursed mummy’ of Amen-Ra was rumoured to be on its way to New York in the hold of RMS Titanic, the curse causing the ship to sink in the early hours of 15 April. The story was in fact fake news, as Murray’s Egyptian souvenir was (and remains) at the British Museum. Of the twelve known dogs travelling on Titanic three survived by being small enough to smuggle off the sinking ship under winter clothing; one lucky dog was a Pekingese called Sun Yat-Sen, named after the first president and founding father of the Republic of China, which was formed on 1 January 1912. The Peke escaped Titanic on Lifeboat 3 with its owners, Mr Henry and Mrs Myra Harper, First Class passengers who also survived after being picked up by the rescue ship, Carpathia.

Travelling with the Harpers was 27 year old Mr Hammand Hassab, a tour guide the couple employed in Cairo and retained as Mrs Harper’s servant. Much unpleasant gossip surrounded the handsome Egyptian whose presence on board perhaps helped fuel the Amen-Ra legend. He too survived via Lifeboat 3 and Carpathia.

Another Peke enthusiast with a connection to the Titanic was millionaire railroad tycoon, John Pierpoint Morgan, whose Pierpoint-Morgan Cup was awarded annually at the exclusive Pekingese Club of America. Although he was not onboard the ship, he owned the White Star line under which company the Titanic sailed.

By coincidence, the most famous British man to lose his life on the Titanic, William Thomas Stead, had a connection to Thomas Douglas Murray through Ada Goodrich Steer. Stead, a journalist and newspaper magnate, was fascinated by the paranormal, and had employed Freer as a subeditor on a spiritualiist magazine he published.

Finding Kylin’s ancestors

As Kylin was given to Ellen by her daughter-in-law, Evelyn, it is probable the dog came via Uncle Murray. Being an adventurer and merchant Murray had business interests in China. The British had long been trading with China importing highly prized goods such as silk, tea, jade and porcelain. Naturally therefore Murray became interested in the profitable potential of the exotic Chinese Lion Dog.

In a chapter ‘The Ancient Palace Dogs of China’ published in The Pekingese Dog by Lillian Smythe (1909) Murray described how he and his equally enthusiastic wife, Anne obtained their first Pekingese:

‘The late Sir Chaloner Alabaster, our Consul-General in Canton told me that it was a great rarity and that during his thirty years’ residence in China he’d never before seen one in Canton, and rarely one of the breed except in Peking itself. In 1896, after five years’ endeavour, we succeeded in getting a pair of Pekingese from the Palace.’

The breeding pair described as ‘well known’ were Ah-Cum and Mimosa weighing 5 and 3lbs respectively and about a year old. Back home in Britain, after a sea voyage of four months, they founded a dynasty. Ah-Cum is famed, even today, as a patriarch of the breed in England. When he died on 2 January 1905 the Murrays presented his body to the South Kensington Museum (now the Natural History Museum) to be conserved as an important animal specimen.

This was an exciting discovery and I wondered if the preserved body of Kylin’s ancestor was still in existence. I soon had my answer through a swift response from the Natural History Museum branch at Tring in Hertfordshire. Yes, Ah-Cum was in their collection and an image was sent.

‘Ah-Cum Pekingese dog’: by permission of the Trustees of the Natural History Museum at Tring

In life Ah-Cum was ‘red with a black mask’ but as is common in aged taxidermy specimens his colour is much faded so he appears a soft gold. He was described as eight inches high at the shoulder, light-boned with straight fore legs, beautiful in colour and carriage and with a tail more like a tuft than a plume.

High-ranking canine residents of the Forbidden City

The Pekingese dog, in all its colours and variety, was bred within the confines of the Forbidden City Palace in Peking, now Beijing in the People’s Republic of China. Current theories hold that the dog was originally developed by Tibetan monks and traded with China’s royalty.

A favoured resident throughout the Palace’s 500 year history, the dog held high status. Only persons of royal blood could own a Pekingese (the penalty for stealing or harming one was death) and all ranks had to bow to the Pekingese, as a heavenly symbol of the Emperor’s power.

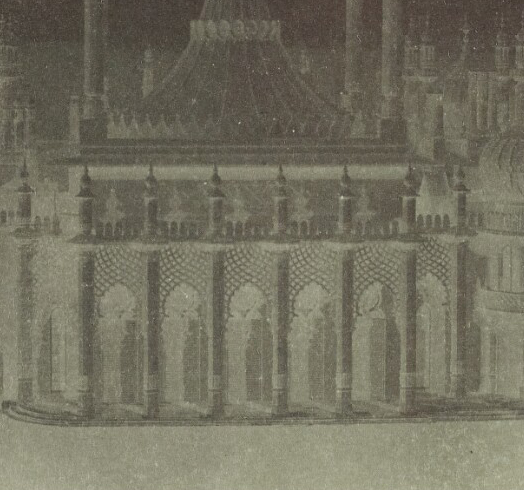

Pekingese Hierarchy cartoon by C. J Allport

The lofty position of the Pekingese is illustrated in a cartoon in the Pekingese Scrapbook showing the divine Buddha at the top of a pagoda. In descending hierarchy level-by-level comes the Pekingese dog, the Imperial family, then courtiers followed by tradesmen and cats. The dark and hellish bottom levels contain fish, insects and ordinary people and finally ghosts, fleas, demons and what looks like a postman but is surely a tax-collector.

In her book Two Years in the Forbidden City, (1912) American travel-writer Miss Katherine Carl gave a glimpse of a rare scene:

‘The dogs at the Palace are kept in a beautiful pavilion with marble floors. They have silken cushions to sleep on and special eunuchs to attend them…around the neck of each was a rich collar with gold bells, tassels and other ornaments in most fanciful arrangement…’

The high status of the Pekingese dog in Imperial China translated to the West once it arrived and remained long after, for the Pekingese in the 20th century became the pampered lapdog of its wealthy and usually female owner. The rescued Peke on Titanic was not travelling steerage.

Ellen Thomas-Stanford was described by her son John as ‘a terrific snob’ so ownership of this splendid little dog of the great Chinese Emperors would have chimed with her ideals.

Dogs, drugs and Queen Victoria

By owning a Pekingese Ellen was following in British royal footsteps as well as Chinese, as Queen Victoria had owned one of the first five Pekingese dogs to arrive in Britain. These Pekes came via ignoble means: the sacking and looting of the Summer Palace in Peking by British and French forces during the Second Opium War of 1860. Amongst the palace ruins the five orphaned puppies were found by Captain John Hart Dunne of the 99th Regiment and all ended up in hands of the British aristocracy. When the Captain returned to England he presented a Pekingese to Queen Victoria for the Royal Collection of dogs and she was duly named Looty. Looty was described as, ‘the smallest and by far the most beautiful little animal that has appeared in this country’. So small was the dog that she made her voyage in Captain Dunne’s forage cap.

Looty (1861) Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

Looty’s portrait was painted by Friedrich Wilhelm Keyl (1821-1871). The artist was told he ‘must put something to shew its size; it is remarkably small’. Accordingly, Looty is shown aside a poesy containing a pansy and a nasturtium flower; small blooms which if held to Looty’s muzzle would mask her face entirely. The richly-coloured setting includes an Oriental vase and a blue velvet dog collar onto which are sewn two little brass bells. The painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1862. Looty lived at the kennels in Windsor Castle until her death in 1872.

The British at this time were not only buying goods from China but importing into the country – and the chief commodity unloaded from British ships was opium, grown and processed in British ruled India and sold in increasingly vast quantities to the Chinese. Some opium was required as a valuable pain killing component in Chinese medicine, but the drug was leeching out into a population that was becoming dangerously addicted to the narcotic effect – to the horror of Chinese officials. The Opium Wars were fought over trading rights, access to Chinese ports and the over-supply of the drug.

Ellen Thomas-Stanford’s ‘looted’ Kylins

The name Kylin is a generic term coined by Victorian antique dealers to describe any kind of fantastic Chinese beast. The word derives from the Chinese qilin, a mythical animal with the head of a dragon and the body of a deer. In 1909 on the puppy’s arrival at Preston Manor Ellen had already started her collection of ceramic Kylins; Chinese temple lions crafted in blanc de Chine porcelain and imported to Britain from China as objets d’art. To Europeans these lions look rather like the Pekingese dog with their bulbous eyes and flattened snouts. One can imagine Ellen holding her new Pekingese puppy against her ceramic collection, and then smiling at the similarity and coining her pet’s name.

Preston Manor Kylin collection photographed in 1914

Ellen was not an antiquarian and so her collection is idiosyncratic. She obtained her ceramic Kylins at random, mostly from antique dealers in Brighton and London. Ellen seems not to have cared for perfection, as some of the lions were cracked in the firing process and so bought already damaged. Fortunately for us today, she kept the receipts rolled into the hollow bases of the figurines. These have since been removed for preservation and make fascinating reading. Ellen paid on average £5 per piece (in a period when the average working wage was around £1 per week).

The largest and costliest pair were bought on 4 April 1913 from Bluett & Son, specialists in Chinese porcelain, of 377 Oxford Street, London. Costing £16 they came with a letter of provenance dated March 13 1902. The author, the previous owner living in Tunbridge Wells, declares,

‘They are in cream glaze and were part of the Summer Palace loot, China March 1860, and I also know who bought them home.’

This last point is important because a great many Chinese objects of bogus origin were sold as genuine Forbidden City wares, the Imperial association adding prestige and inflating the price.

In 1933, the year after Ellen’s death and a month before Preston Manor opened to the public as a museum, curator Henry Roberts consulted the Department of Ceramics and Ethnography at the British Museum regarding the blanc de chine lions. Ellen believed her Kylin collection to be rare 15th century Ming Dynasty and Henry wanted to get facts correct for his new guidebook. To be fair to Ellen, receipts show she was sold some Kylins identified (probably in good faith) as Ming.

The British Museum expert, Mr Hobson replied with disappointing news:

‘The ‘Kylins’ aren’t older than the 17th century. Probably most of them are the 18th.’

However, he adds, ‘incidentally the term Kylin is commonly applied to the Pekingese-dog-like creatures which are intended to be lions. “Buddhist Lion” is a more correct name to use.’

Poor Ellen; the Ming collection of which she was so proud was no such thing and her Pekingese puppy was the reject of the litter!

Kylin’s arrival at Preston Manor

We know from the inscription on Kylin’s tombstone that she lived from 1909 to 1924 so we have the year she arrived in the house.

Tombstone: Kylin Faithful & Fearless

Looking through the Preston Manor visitor book for the year 1909 I came across a page full of clues as to the exact day. On Friday October 28th, 1909 I found the signatures of John & Evelyn Bennet-Stanford along with the name of fellow Peke aficionados, the Gordon-Lennoxs. This name is one of the most important in the Pekingese-breeding set of the Edwardian period. Of the five puppies looted from the Summer Palace in 1860 two were given to the Duke and Duchess of Richmond and Gordon. These were used as a breeding pair by the Duke and Duchess’s son, Lord Algernon Gordon-Lennox, who with his wife established the famous Goodwood line of Pekes and founded the Pekingese Club in 1904.

Almost certainly Kylin was given to Ellen Thomas-Stanford by her daughter-in-law as an early 61st birthday present, for Ellen’s birthday fell two weeks later, on 9 November.

Preston Manor visitor book 28 October 1909

A superior specimen

Portrait of Chu-Ki, 1927

The other Pekingese portrait to be seen at Preston Manor is that of Chu-Ki who belonged to Ellen Thomas-Stanford’s half-sister, Diana Magniac. Diana died in 1956, bequeathing the painting to Preston Manor. A label on the frame helpfully gives Chu-Ki’s lineage and through this he can be identified as a dog of superior merit to Kylin. Chu-Ki (kennel name, Chuang-Tu of Alderbourne) was son of Chu-Erh of Alderbourne, another Pekingese dog that made history. His pedigree includes not only Ah-Cum but the renowned Pekin Peter, Pekin Prince, Pekin Princess and the first bitch Champion, Gia-Gia.

Famous Edwardian Pekingese dogs

Chu-Erh was bought by breeder Mrs Ashton-Cross as a new-born in 1905 for the astronomical sum of £150. To put this into perspective, £150 in 1905 is equivalent in purchasing power to £17,686 in 2018. Chu-Erh was one of the most successful stud dogs of the pre-1914 era, siring at least nine champions. Mrs Ashton-Cross instigated the famous Alderbourne Kennel in the late 1890s. Her four daughters were famed for wearing white gloves in the show ring to avoid transferring the slightest mark of grease onto their Peke’s precious coats.

Chu-Ki’s portrait by Arthur John Elsley is dated to 1927. It owes much to Looty’s portrait in the Royal Collection in that his diminutive stature is shown by his being posed on a small occasional table aside what looks like an Oriental ashtray. He stands on a length of emerald-green silk, his glossy coat reflected in the mahogany polish of the table. Chu-Ki displays a prized Peke-marking, the white flash on his forehead, known as the mark of the Buddha.

A poem, The Pearls, attributed to the Dowager Empress Tz’u-hsi or Cixi (1861-1908), but believed to be a hoax-piece by early British breeders, describes the perfect Pekingese dog. A section reads:

‘Let the Lion Dog be small, let it wear the swelling cape of dignity around his neck, let it display the billowing standard of pomp above its back.

Let its face be black, let its forefront be shaggy, let its forehead be straight and low.

Let its eyes be large and luminous, let its ears be set like the sails of a war junk, let its nose be like that of the monkey god of the Hindus.

Let its forelegs be bent so that it shall not desire to wander far or leave the Imperial precincts. Let its body be shaped like that of a hunting lion spying for its prey.’

Pekingese Pride and Prejudice

Portrait of Peter, early Twentieth Century

I have given many guided tours that include the Preston Manor dog portraits and without fail it is the portraits of the non-pedigree dogs that are favoured by visitors. Peter and Pickle are especially admired: Peter, with his disgruntled stare and greying muzzle; and untidy scamp Pickle, sat without ceremony on a tattered rug and flagstone floor. Both dogs speak of the familiar: they are dogs we might own with homely names we might have given.

However, Kylin and Chu-Ki read as alien creatures with their outlandish Mikado names and unfathomable histories. These animals come weighted with a bias towards their being ‘the posh lady’s dog’, for who can forget the cossetted Pekingese, Tricki-Woo, in All Creatures Great and Small, the often repeated 1970s’ BBC television drama about pre-war Yorkshire veterinary surgeons.

Dowager Queen Alexandra with a Pekingese dog

This sense of the Peke being ‘not one of us’ ordinary folk originated in the late Victorian and Edwardian era when certain possessions (including pets) were signifiers of high-class, good taste and, if possible, a connection to the Royal Family. The Thomas-Stanfords owned a Rolls Royce motorcar and entertained royalty at Preston Manor, so naturally they were proud to own a Pekingese dog.

Little Jim

Discovering the Pekingese’s ancient Tibetan and Chinese origin, and reading the story of those five tiny puppies, refugees from war travelling on ship as precious cargo in 1860 to start their new life as canine immigrants to Britain, makes me look afresh at the Pekingese dog as a breed and at the individual characters of Chu-Ki and Kylin: Preston Manor’s ‘Faithful and Fearless’ Lion Dogs who, though exalted by Chinese Emperors, the wealthy Edwardian British upper class and American millionaires, deserve their position as one-of-us equals to Peter and Pickle and little Jim the Yorkshire terrier immortalised in stone and enduringly popular with visitors to the house.

Preston Manor re-opens for the summer season on Sunday 1st April. The dog portraits can be seen on the ground floor at the foot of the staircase. Kylin’s tombstone is in the pet cemetery in the walled flower garden.

Paula Wrightson, Venue Officer, Preston Manor