Whose Botany Is It Anyway? How Colonial Powers Thought They Knew Better Than Traditional Custodians of the Land

There is no doubt that the botanical expeditions undertaken by European powers in the colonial era, contributed significantly to western knowledge.

While western societies were benefiting from this exploration though, Indigenous communities around the globe – and the natural world itself – were paying a price.

Maintain a ‘balance’

These communities, with their animist beliefs that natural phenomena have a living soul, have a deep understanding of their ecosystems. They place great value on managing their resources sustainably. It is important to Indigenous people to maintain a ‘balance’ in the natural world.

For example, the Maya civilization in Mesoamerica practiced agroforestry, a sustainable land-use system that combines the cultivation of crops with the management of trees. They planted a variety of crops, such as maize, beans, and squash, alongside fruit and nut trees. This approach provided food, timber, and other resources while maintaining soil fertility and preventing erosion.

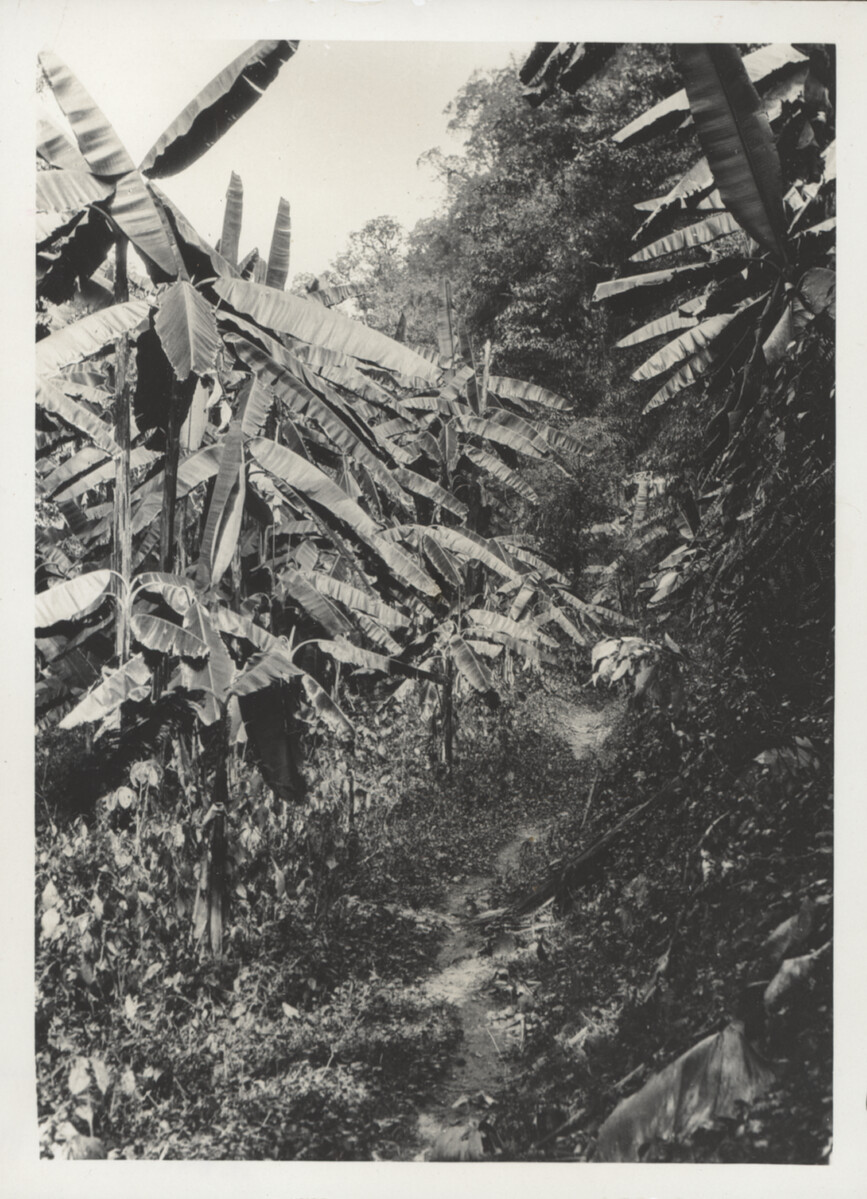

Similarly, communities of the Amazon rainforest still practice agroforestry systems known as ‘forest gardens’ or ‘chacras’. These gardens are carefully designed to mimic the natural forest ecosystem, with a mix of fruit trees, medicinal plants, and crops. The diverse plantings provide food, medicine, and other resources while preserving the integrity of the forest and supporting biodiversity.

First Nation tribes in North America developed sophisticated water management systems. The Hohokam people in the arid Southwest used their deep understanding of local hydrology to construct canals and reservoirs to capture and distribute water for agriculture, and to use water sustainably.

Pacific Islander communities established sustainable fishing practices to ensure the long-term health of marine ecosystems. The practice of ‘tabu’ or ‘ra’ui’ involves temporarily closing off certain fishing areas to allow sea populations to replenish. This traditional marine management approach helps support fish stocks and protect coral reefs, while still sustaining the livelihoods of local communities.

And Aboriginal Australians have long practiced controlled burning to manage their landscapes. They use fire to promote the growth of certain plants, while controlling invasive species, and reducing the risk of larger, destructive wildfires. This traditional fire management technique helps maintain biodiversity, also regenerating vegetation, and supporting the survival of culturally significant plants and animals.

Colonial disruption

These sustainable practices were disrupted by the arrival of colonial powers.

As colonisers claimed new territories, Indigenous communities were often pushed off their ancestral lands, leading to the loss of their traditional knowledge tied to specific landscapes.

The rubber boom in the Amazon rainforest during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, is a stark example of this disruption. Indigenous communities were forced into labour and their lands were seized.

Even where communities were not forcibly removed, Indigenous agricultural practices were often suppressed and the deep knowledge the communities had for their local eco-systems was dismissed.

As colonial powers imposed their own agricultural practices, they disregarded Indigenous knowledge. This led to the erosion of traditional farming methods and the loss of crop diversity. In parts of Africa, for instance, European colonisers replaced Indigenous food crops with cash crops like cotton or coffee. This disrupted the self-sufficiency and resilience of Indigenous communities, leading to food insecurity as well as a loss of cultural identity.

Botanical knowledge

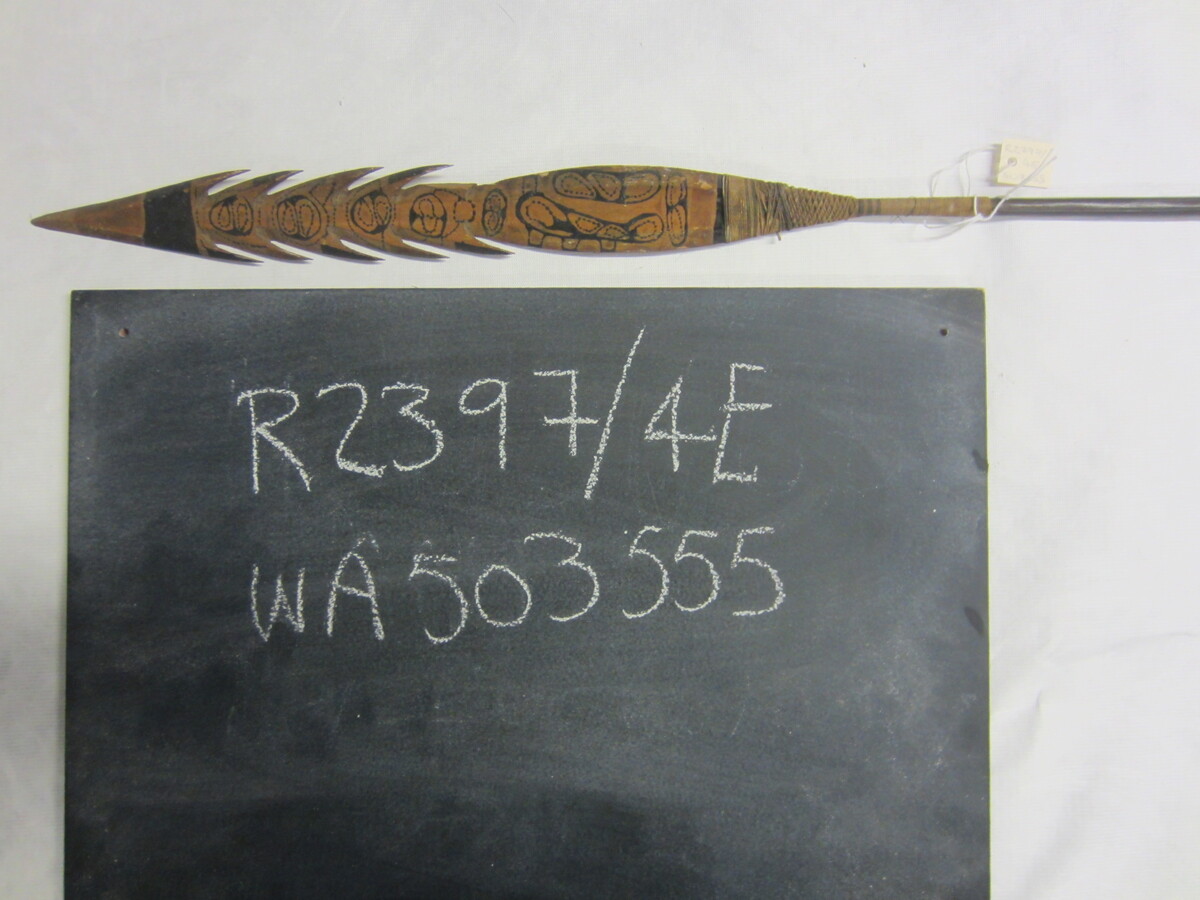

The colonial era quest for botanical knowledge led to the formation of many natural history museums and collections, including Brighton’s Booth Museum of Natural History. When European colonisers ‘discovered’ new plant species in the territories they conquered, they often failed to recognise or respect the traditional botanical knowledge of Indigenous peoples. Instead, colonisers viewed themselves as the authorities on natural history and taxonomy.

Native American peoples used a wide variety of plants for medicinal purposes. They had knowledge of plants with analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, and other healing properties.

For example, echinacea was used by Plains tribes to boost the immune system, while yarrow was used as a natural pain reliever and wound healer.

The arrival of European settlers led to the suppression of these Native American healing traditions, as European medical practices were imposed, undermining the Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants.

Aboriginal people also have a rich understanding of the medicinal properties of various plants. They have developed remedies for treating ailments and injuries using plants found in their local environments. For instance, tea tree oil, derived from the leaves of the Melaleuca alternifolia tree, has been traditionally used for its antiseptic properties. Other plants, such as kangaroo apple, pigweed, and native mint, have been used for their medicinal properties as well.

The western world is now incorporating this knowledge into our medicinal practices, though often without acknowledging their longstanding use by generations of Indigenous people.

Consequences

The consequences of the disruption to Indigenous cultures and the suppression of their knowledge are still felt today. Deforestation and loss of biodiversity threaten not only Indigenous cultures and livelihoods, but also have a global effect, for example as the planet warms because of climate change due, in part, to this deforestation.

Acknowledging and respecting the traditional knowledge of Indigenous peoples can be one more tool in our toolbox as we work towards a more sustainable future.