The Dark Side of Botany: How the Myth of the Harmless Botanist Conceals Colonial Realities

In popular culture botanists, both colonial era and modern, are depicted as harmless, gentle scientists. From Robert Louis Stevenson’s character Dr Henry Jekyll to Seymour Krelborn in the musical ‘Little Shop of Horrors’, fictional representations cement the botanist in our minds as a kind, meek, often nerdy character incapable of inflicting harm.

In reality, botanists were instrumental to Britain’s colonial ambitions. Many were directly or indirectly involved in colonial projects that included violence, exploitation and the displacement of indigenous people.

Indeed, botanical expeditions were sometimes accompanied by military forces. Botanists witnessed or were directly involved in acts of violence carried out by these forces.

Colonial-era botanists from the UK served the interests of the British Empire. As botanists explored fauna and flora, they gained valuable knowledge about geography, climate and natural resources. This information was shared with colonial powers which helped ease further expansion and control.

For example, botanist Sir Joseph Banks accompanied Captain James Cook on his first voyage to Australia and New Zealand in 1770. Banks’ accounts of the native plant life helped convince the British government to establish a penal colony in Australia.

Botanists found crops that could be exploited for economic gain, again providing this information – or even active help – to colonial powers. For instance, rubber trees were smuggled out of Brazil by botanist Henry Wickham and planted in British colonies in Asia. This resulted in deforestation, loss of biodiversity and the displacement of indigenous communities , which has continued in former colonies.

Habitat destruction

The 2009 movie Avatar explicitly tackles colonial exploration and conquest and is sympathetic to the fictional Na’vi people. There are obvious parallels to European colonialism. The societal structures and animistic beliefs of the Na’vi people also bear more than a passing resemblance to indigenous peoples encountered during the colonial era. Even in this film, botanist Dr Grace Augustine is shown as a caring scientist, dedicated to preserving the planet’s ecosystem.

In reality, colonial botanists often engaged in extensive habitat destruction. They would clear land, remove vegetation, and disturb natural habitats to collect plants.

Oil palms, native to Africa, are grown in vast plantations built over rainforests in places such as Indonesia and Malaysia. As a result, “the plight of the orangutan in Indonesia has reached a critical stage.”

The pollination dynamics of plants weren’t considered when plant species were removed from their native habitats.

Pregnant bumble bees and other European bee species were transported to Aotearoa, New Zealand, to pollinate clover so clover pastures could be grown for sheep grazing. Large swathes of New Zealand are now covered in European clover pastures instead of native grass land or forests. This is now costing millions of dollars to put right, as conservationists replant native flora to restore the habitats.

Botanists often collected and transported specimens from one region to another. These introduced species could become invasive and outcompete native flora and fauna, leading to a loss of biodiversity.

Ecological damage

The introduction of European rabbits, for example, by botanist Thomas Austin in Australia in the 1850s resulted in widespread ecological damage. As the rabbits rapidly multiplied, they:

- caused widespread habitat destruction;

- induced soil erosion due to their extensive grazing;

- affected the survival and reproductive success of native herbivores as they competed with them for food; and

- introduced several diseases to Australia, including myxomatosis and rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD). These diseases caused widespread mortality in rabbit populations, which also affected native predators that had come to rely upon rabbits as a food source, with the displacement or extinction of native animals.

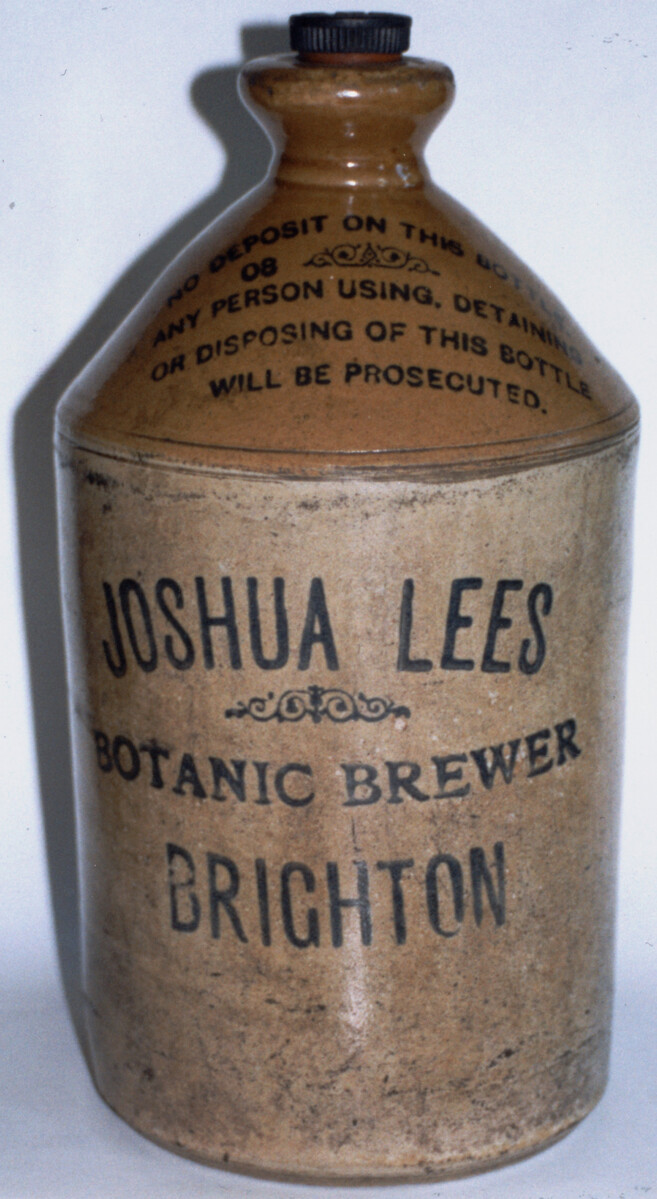

The Regency period in Britain coincided with the height of the British Empire and colonial expansion. As the British established colonies in places like India, Australia, and the Caribbean, there was a growing interest in the ‘exotic’ plant life found in these distant lands.

Exotic botany

The Royal Pavilion Garden is a prime example of this interest in ‘exotic’ botany. The Prince Regent was an avid collector of rare plants. Under his patronage, botanists like Francis Masson travelled to South Africa and the Azores to collect plants for the Pavilion Garden, displaying a wide array of ‘exotic’ flowers, shrubs and trees. At the same time, there was often accidental transportation. For example, botanists unwittingly introduced European snails to the Azores, which led to the extinction of many native snail species. Most of these extinct snails can now only be seen in museums – including the Booth Museum of Natural History.

As well as the damage caused in native lands, some plants brought back to Britain proved to be invasive species that are still causing environmental damage today.

Himalayan balsam, with its attractive pink flowers, was introduced to the UK in the mid-19th century as an ornamental plant. It forms dense stands that outcompete native plants, leading to a loss of biodiversity particularly along riverbanks and waterways. Its tall growth shades out other vegetation, exacerbating the problem. The plant also tends to spread rapidly, with its seeds being easily dispersed by water, animals, and human activities.

And many gardeners know the frustrations of Japanese knotweed, also introduced in the mid-19th century as an ornamental plant.

A highly invasive species, Japanese knotweed (native to East Asia in Japan, China and Korea) has not only caused significant harm to British nature, but it can also damage infrastructure. Its roots can penetrate through cracks in roads and buildings, causing structural damage. Controlling and eradicating Japanese knotweed has proved challenging, and it remains a persistent problem in many parts of the UK. A recent study has calculated that Japanese knotweed costs the UK economy £246.5m a year.

Colonial legacies

The myth of the harmless botanist conceals the harmful effects of botanical exploration during the colonial era. But recognising the dark side of botany and the colonial legacies it carries is crucial for understanding the historical and ongoing impacts of botanical exploration.

At Brighton & Hove Museums we are undertaking a more nuanced and critical examination of the motivations, methods, and consequences of plant collection and display in our gardens. By acknowledging and learning from the mistakes of the past, we can strive for a more responsible and inclusive approach to botany that respects the interconnectedness of nature, culture, and history.