Conservation Plan

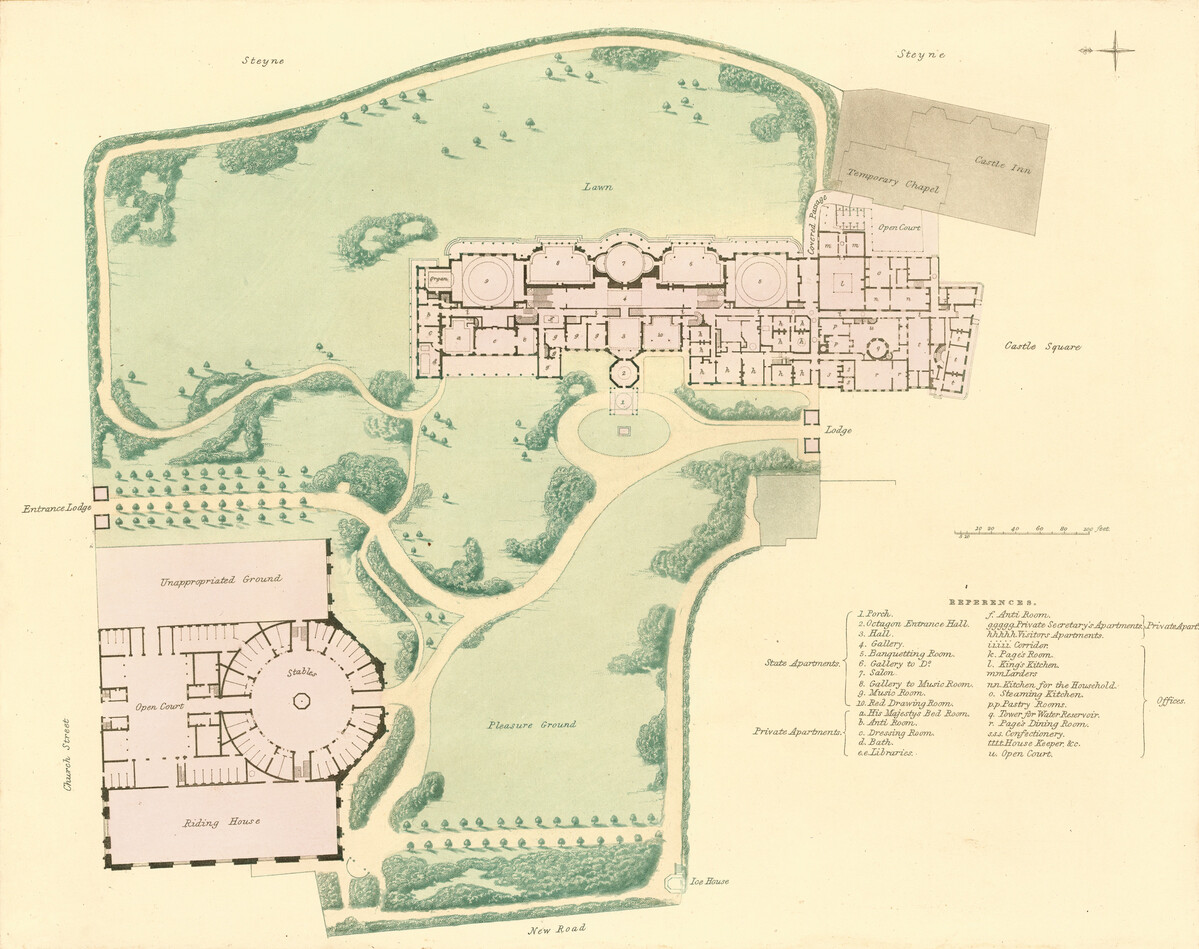

Nestled within the heart of the city of Brighton & Hove is a very rare example of a royal pleasure pavilion, where the architecture and landscaped setting (our garden) survives intact. It was designed for the Prince Regent, later King George IV (1762-1830) in the early 19th century in the Picturesque style by the nationally significant and influential architect and landscape designer John Nash (1752-1835), with planting by the royal gardener William Aiton (1766-1849).

Today, the Royal Pavilion Garden is a much-loved small green open space in the centre of a busy city. At least 1.5 million people visit it every year. Other comparable landscape designs by John Nash are London sites and much larger: Buckingham Palace’s garden is 40 acres whilst St. James’s Park is 57 acres and Regent’s Park is 166 acres. The Pavilion Garden is miniscule in comparison – just 8 acres. This will influence how we need to go about restoring our tiny fragile space, balancing the unique and significant history, against the requirements of modern much used and loved city garden.

A conservation plan – what’s that?

A Conservation Plan has been produced for the Royal Pavilion garden which has enhanced our understanding of the importance of this historic space. Written by historic garden experts, our Conservation Plan is a document that describes the importance of the Royal Pavilion garden as a historic site and underpins how it needs to be looked after. It looks at many aspects of the garden including its history and helps uncover new stories which can improve how we interpret the space and share its fascinating history with visitors. A Conservation Plan also highlights any potential threats that may harm the unique heritage of a site, as well as outlining suggested improvements to help maintain its long-term sustainability.

The Landscape Architect – John Nash

John Nash was one of the most important and prolific architects of his day, and his work as a designer of many famous landscape schemes was just as important and long lasting. The Royal Pavilion Garden was a testing ground for his later royal commissions in this style. It is the earliest of his domestic schemes to survive intact with the principal building he designed still showcased at its heart. The garden demonstrates his early approach to royal landscaping which he later developed in scale and complexity.

The design of this garden was intended to provide a setting for the magnificent Royal Pavilion. To do this Nash developed a style in which flowers and planting were used in a subtle naturalistic way. The planting included rarities such as China roses (especially Rosa semperflorens), tiger lily and dahlia newly introduced to Britain through the trade routes developed by the country’s ever expanding colonial ambitions of the early nineteenth century. These plants were used as jewel-like splashes of colour. The trees formed a framework, with a high proportion of elm as specimens (it has been said that English elm was the Prince Regent’s favourite tree).

The Royal Gardener – William Aiton

William Aiton was the leading horticulturist of his day, and his influence on the Pavilion Garden was immense. He designed the planting, ordered the plants and oversaw their planting This makes the garden a rare example of an Aiton and Nash collaboration which survives largely intact.

The Pavilion Garden saw the very early use of an innovation in planting schemes. As fashions change in designing buildings, they also change in the gardens that surround them. Before the creation of the Pavilion Garden, it was popular to plant lots of different types of plants together. Aiton turned that on its head and grouped many of the same plants together in groups to create a striking visual effect. This new style of planting for visual effect was hugely influential on future fashions in gardening. The concept used here in Brighton in the early 1800s is still seen in many planting schemes in modern gardening today.

The Pavilion plant lists of 1817-29 still survive in the archives and are an important source for replanting the garden. They tell us a huge amount of fascinating information including the colours of the plants used in the original garden. This level of information rarely survives from individual historic gardens and is of immense value to our restoration project as we can use them to recreate the planting schemes with the original colour palette.