The Shining Lights of Service and the Indian Hospital at the Royal Pavilion

The Shining Lights of Service

Adelaide Balcony, Royal Pavilion façade

11 November – 28 January 2024

Artist Chila Kumari Singh Burman MBE has created The Shining Lights of Service, a unique, multi-coloured light installation to commemorate the Indian Hospital at the Royal Pavilion during the First World War.

The artwork remembers the soldiers cared for in the Royal Pavilion between 1914 and 1916 when it was used as a hospital for Indian soldiers wounded in the First World War. Burman’s colourful neon sculptures draw on the spectacle of the Pavilion interiors, where Asian symbols and motifs intermingle with signs of British imperialism.

This new commission is an IWM 14-18 NOW Legacy Fund Commission in Partnership with Brighton & Hove Museums and in Collaboration with Believe in Me CIC

Film interviews

Please scroll down to the end of this page for an interview with Chila Kumari Singh Burman and a new film about the Indian Hospital.

The artist

Chila Kumari Singh Burman MBE works across a wide range of mediums including printmaking, drawing, painting, installation and film. She was born in Liverpool to Punjabi-Hindu parents. Burman’s work often explores the cultural syntheses she experienced growing up in Britain. Popular culture and high art are combined in her work, creating powerful, vibrant images across different media that reflect on cultural identity, representation and gender.

The commission

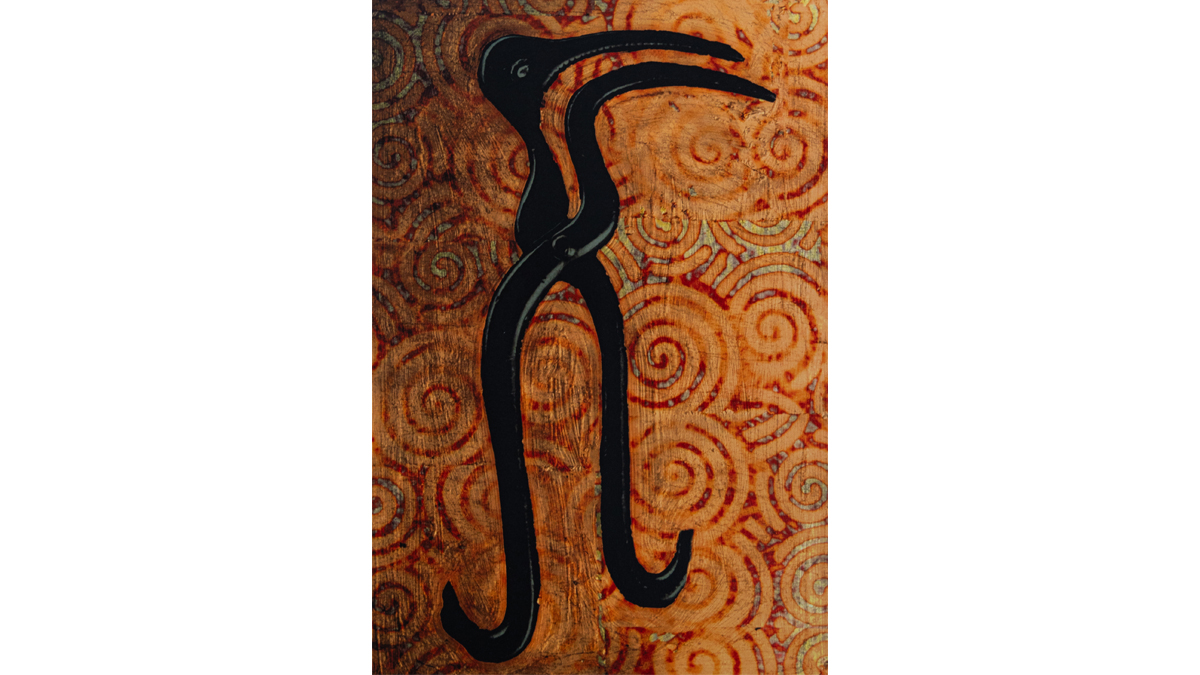

Burman’s neon light installation celebrates Indian myths and customs, conflict and cultural fusion against the Indian-inspired silhouette of the Royal Pavilion. Motifs drawn from the opulent interiors of the Pavilion are placed side by side with Indian medical instruments, a reflection on the surroundings in which the Indian soldiers were cared for and a sobering reminder of the wounds inflicted by the war that brought them here.

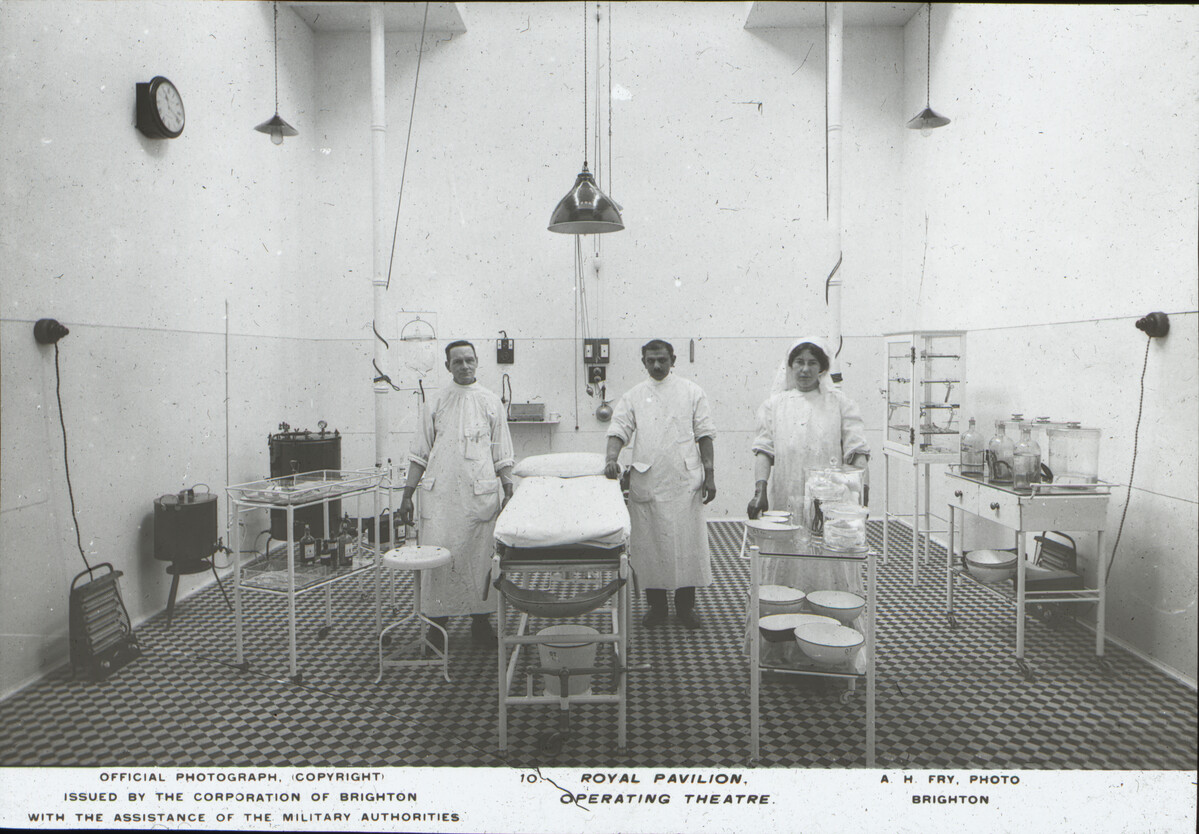

The Indian Hospital at the Royal Pavilion was built as a state-of-the-art medical facility using modern western medical practices. The traditional Indian Ayurvedic medical tools in Burman’s installation are a reminder of the Indian soldiers’ deployment from their home country to the Western Front during the First World War.

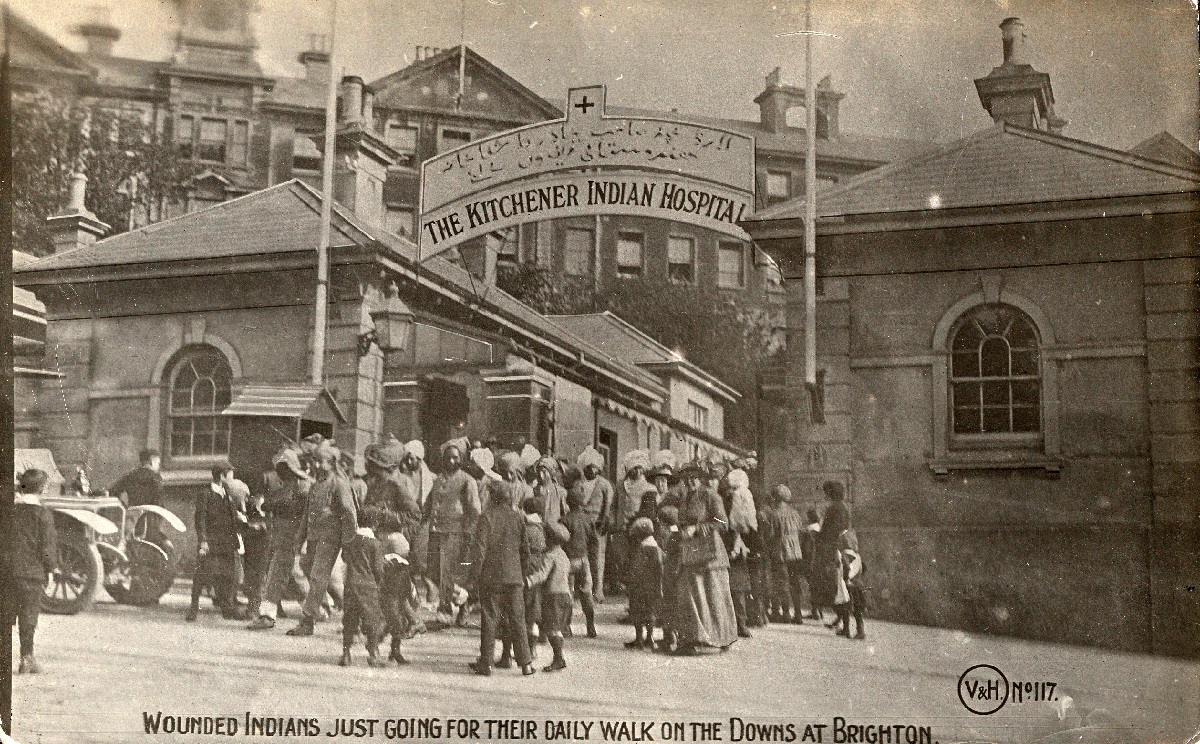

Burman’s installation rises from the Adelaide Balcony overlooking the lawn where over 100 years ago Indian soldiers were photographed during their convalescence. This is one of many images used as propaganda during the war by the British in India. The Shining Lights of Service commemorates the Indian Hospital at the Royal Pavilion and the role of Indian soldiers in the First World War.

The Indian Hospital at the Royal Pavilion

The Indian Army played an important role during the First World War. At the outbreak of war in August 1914, the British Army was relatively small, and the Allied troops were quickly outnumbered by advancing German soldiers.

Reinforcements were brought in from Britain’s colonies across the world. The Indian Army were the largest standing army and were the first to mobilise and the first to arrive in France in October 1914. British India at this time comprised of present-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Burma.

Over the course of the war, over 620,000 Indian men served as combatants overseas as part of British Empire forces, with a further half a million men in non-combatant roles such as medical personnel, miners and signallers. Almost 140,000 came to Europe. The first divisions were initially on their way to Egypt when they were diverted to France, in response to devastating casualties in the British Expeditionary Force.

© IWM

Arriving in France in light khaki uniforms, they were unequipped for the cold and damp climate of a European winter. Warmer clothing was not provided for many months. The intensity of the war in the trenches of the Western Front, with machine gun fire, heavy artillery and poison gas led to huge numbers of casualties. Makeshift hospital facilities were quickly overrun with injured soldiers.

A new group of hospitals for Indian soldiers was established on the south coast of England, where patients could be transported from northern France. Three of these hospitals were in Brighton. The Royal Pavilion Estate, consisting of the Royal Pavilion, the Dome and the Corn Exchange, York Place and Pelham Street schools, and a former workhouse.

In December 1914 the first Indian troops arrived in Brighton from Southampton by hospital train. The Royal Pavilion hospital became the most famous of the Brighton hospitals. A misleading impression was given that the Royal Pavilion was still an occupied royal palace and that George V, both King and Emperor of India, had given up the building for use by Indian soldiers. It was hoped that this would reinforce a sense of loyalty to the King-Emperor. Initially the Royal Pavilion was not considered as a potential venue for a hospital by the Brighton authorities.

Sir Walter Lawrence, who was Commissioner for Sick and Wounded Indians in England and France, wrote in his memoir,

It is hard to imagine quite how the pier would have been transformed into a suitable hospital.

In creating these hospitals, enormous efforts were made to conform to the religious and caste sensitivities of the soldiers, from food preparation, bathing, worship and in death. There were 9 kitchens set up for the Royal Pavilion Estate, and each kitchen had caste cooks, with a high caste cook in charge. Soldiers were Hindu, Muslim and Sikh. Notices throughout the hospital were printed in Urdu, Hindi and Gurmukhi.

This attention to detail in the care of Indian soldiers was widely publicised in Britain and India, in order to promote loyalty to the British Raj. Most of the recruits came from the north of India, particularly the Punjab and from rural areas. Most of the soldiers were farmers or labourers, and usually illiterate. Soldiers dictated letters home via the few who could read and write. All letters were subject to censorship by the military authorities, who kept a close watch on what was being written back to India.

The Royal Pavilion Estate hospital was unique. Although it had not been in Royal ownership for 64 years, the interiors still appeared fantastical and overwhelmingly opulent. Even with the carpets covered in lino and the walls partly boarded up, soldiers slept in beds under lotus shaped and dragon chandeliers, with chinoiserie walls.

This hospital was photographed, painted and filmed; postcards and photographs of the soldiers in the royal palace and garden were distributed widely in India. No other hospital received such attention. Although medical facilities in all the hospitals on the south coast of England were high compared with makeshift hospitals in other areas of the war, it is the Royal Pavilion that gave soldiers a strange and unique story to tell.

Another Brighton hospital, the former workhouse, renamed the Lord Kitchener Hospital, was rarely photographed and operated under much more restrictive military rule.

However, even the opulence of the Royal Pavilion hospital could not distract many soldiers from the belief they were simply being cared for in order to send them straight back out to war.

There was also a feeling of containment. Indian soldiers were not free to wander around Brighton at leisure. A fence was erected around the Pavilion garden, which prevented potential liaisons with local women or Christian missionaries, both of which were a concern for the British military authorities. Soldiers were taken on supervised tours around the town.

After the Indian Army were transferred from the Western Front to Mesopotamia in December 1915, Brighton’s Indian hospitals received no more casualties. In just over one year, over 2000 patients were treated at the Royal Pavilion Estate hospital.

The Shining Lights of Service, an Interview with Chila Kumari Singh Burman MBE and Dr Kiran Sahota

The Royal Pavilion and the Indian Soldiers of the First World War

An IWM 14-18 NOW Legacy Fund commission in partnership with Brighton & Hove Museums co-produced by Believe in Me CIC