“The gayest and most splendid colours”: George IV proudly embraces his feminine side at Brighton’s Royal Pavilion

Chinoiserie in the decorative arts and interior decoration had for a long time been associated with women and their spaces, possibly because it was associated with lightness, frivolity and lack of seriousness. In this blog post, curator Alexandra Loske casts a light on how George IV turned this notion on its head and possibly challenged gender norms of his time. He was certainly heavily inspired by his sisters’ and his mother’s taste in Chinese export ware and chinoiserie decorations.

The Royal Pavilion is arguably the greatest and most comprehensive example of the ‘chinoiserie’ style in interior decoration and the decorative arts in general in this country. Inspired by Chinese and Japanese culture and enabled by the ruthless East India Companies importing goods to Europe, including decorative objects such as colourful porcelain, silks, lacquer and hand painted porcelain, it is a style that borrowed irreverently from East Asian art without fully understanding or acknowledging it.

It goes without saying that this was a style almost exclusively employed by the rich and privileged, and – in the case of the Royal Pavilion – it was court style. Yet, it was a joyful and creative fashion largely based on uninformed admiration for Chinese culture and history. At the peak of the style’s popularity, in the mid-18th century, cabinets panelled with Chinese lacquer, bedrooms hung with Chinese birds-and-flowers wallpaper, collections of Asian porcelain on mantelpieces etc, were mostly associated with women and women’s spaces. The lightness, lack of seriousness, and strong colouring of chinoiserie decorations did not fit the image of eighteenth-century masculine sophistication. Only rarely would you find chinoiserie elements in formal state rooms or in men’s private apartments. This was a style for closets, small “cabinets” and private rooms.

Our George turned all this on his head, and – perhaps unwittingly – challenged some gender norms of his time. He not only reinvented the style almost single-handedly in the early nineteenth century (he first introduced a Chinese theme into the interiors of the Royal Pavilion in 1802), but also applied it in an unbridled manner, in almost every room of his party palace in Brighton, not caring about its associations with femininity.

Nowadays we might call it ‘camp’, a label that did not exist at the time, but I think George would not have objected to it. In 1833 the local author John D Parry published a detailed description of the Pavilion’s interiors in his book Historical and Descriptive Account of the Coast of Sussex, in which he notes that

True, the word gay then still had a different meaning, but the general sense of joyful opulence and frivolity of the Royal Pavilion had already been noticed.

George was heavily influenced and quite possibly first inspired by the women in his family and their take on chinoiserie. A painting by Johann Zoffany shows his mother Queen Charlotte in a room in Buckingham House (later Buckingham Palace) in c.1765, in the company of her eldest sons George and Frederick, aged just two and one.

The princes are sporting fancy dress costume: George is impersonating a character from Homer’s classical poem The Odyssey, while Frederick wears a Turkish-inspired outfit. Charlotte, too, was known to have worn ‘dress a la turque’ and attended masquerade balls. On the mantelpiece, two Chinese ‘nodding figures’ can be seen, which appear almost identical to those later displayed in the Long Gallery of the Royal Pavilion. Did the young Prince of Wales play with them? Did he perhaps break them?

George would also have been familiar with the substantial collection of blue-and-white china (export ware as well as European imitations) introduced to the English court by Queen Mary II (r. 1689-1694) at Hampton Court and Kensington Palace.

Queen Charlotte had several rooms at Windsor Castle designed in a chinoiserie style or decorated with Chinese porcelain. At Frogmore House in Windsor Great Park the creativity of female members of the Royal Family resulted in several complete chinoiserie schemes in the early nineteenth century.

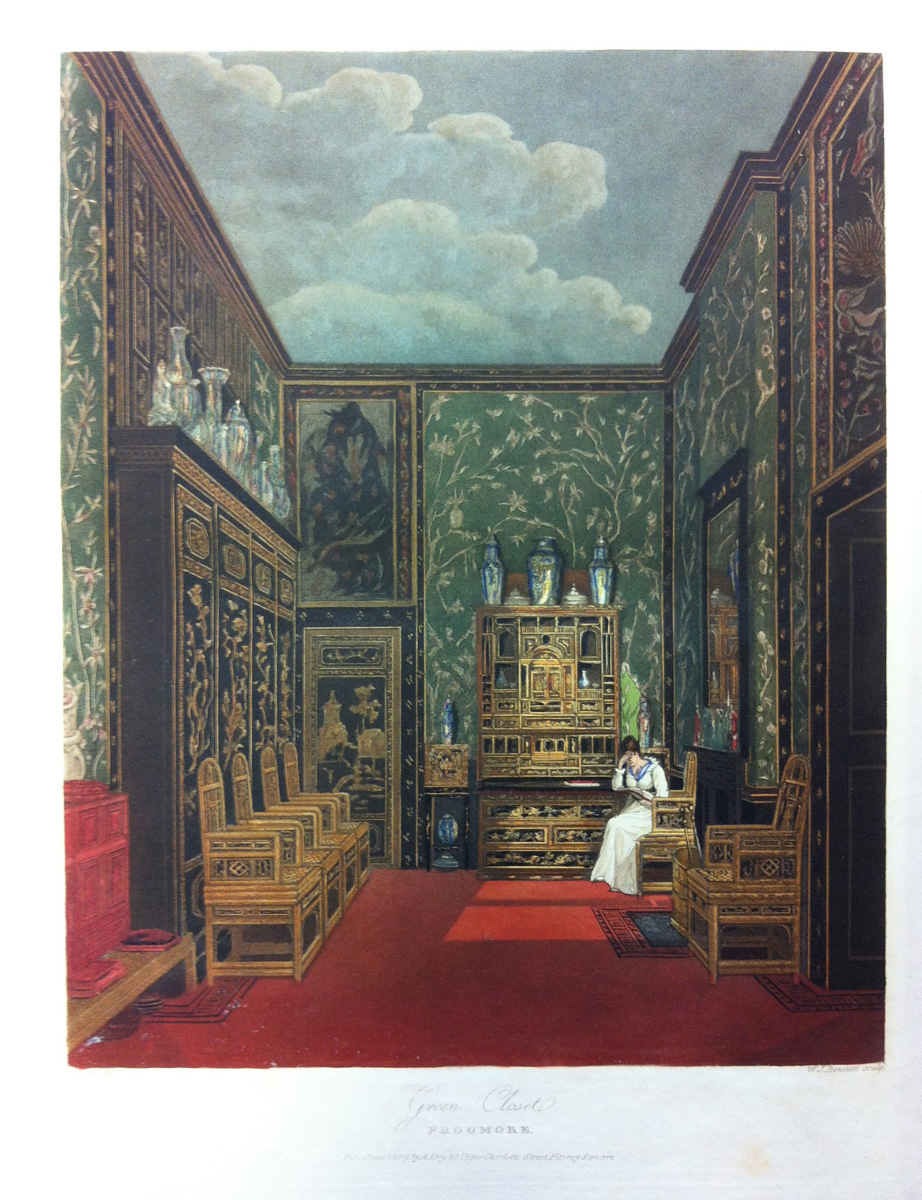

Frogmore House had long been associated with female royal occupants. From 1795 onwards it was frequently used for fetes, concerts and garden parties arranged by some of George’s sisters, including Princesses Elizabeth and the Princess Royal (Charlotte). Elizabeth was particularly interested in interior decoration. She was probably the designer of three Chinoiserie rooms at Frogmore: a (Red) Japan Room, the Green Closet and Black Japan Room, two of which she appears to have partly painted, or ‘japanned’ herself. ‘Japanning’ (imitating Asian lacquer) had been considered a female accomplishment since the seventeenth century, an acceptable pastime for women.

In ca. 1758, Robert Sayer published one of the most important source books for chinoiserie motifs and pattern, with the telling title Ladies Amusement: Or, The Whole Art of Japanning Made Easy. It contained drawings and design by Jean Pillement, some of which may have been influenced the decorations in the Royal Pavilion. It is highly likely that George’s mother and siblings used this book, too.

Women turned this pastime into an opportunity for nonconformity and transgression, and over time chinoiserie would become an indicator of creativity and novelty – sometimes even danger and perceived promiscuity.

This can still be seen today in films and TV programmes, where rebellious and daring women are often shown in rooms decorated with Chinese wallpaper. Recent examples are the BBC series Gentleman Jack (Anne Lister’s lover’s bedroom), a recent TV adaptation of Nancy Mitford’s The Pursuit of Love, where Linda’s decadence is indicated in her wedding photos by a blue-ground Chinese wallpaper. You can even spot it in the Paddington movies, where the wit and creativity of Paddington’s “mother” is filmically represented by the actor Sally Hawkins drawing and writing in a room decorated with a red-ground Chinese wallpaper.

In a contemporary publication, Pyne’s Royal Residences (1819) Frogmore’s Green Closet is described as an ‘apartment fitted up with original Japan, of a beautiful fabric, on a pure green ground. The cabinets and chairs are of Indian cane.’

Tellingly, both the red Japan Room and the Green Closet are clearly depicted as female spaces in the accompanying illustrations: both images show the rooms occupied by seated women, quite possibly the princesses themselves.

Some of the numerous Asian objects displayed in the rooms may have been gifts by the Qianlong Emperor (1711 –1799), presented to George Macartney’s Embassy to China in 1792 to 1794, suggesting that at least some of the interior consisted of Chinese materials and objects. The images created by artist William Alexander (1767– 1816), who accompanied the Embassy, were used by George’s interior decorators John and Frederic Crace in the creation of several schemes and designs for the Royal Pavilion, for example the walls of the Music Room and the colourful Chinese figures on the staircase landings and some chandeliers and lanterns.

It is unclear whether these rooms at Frogmore preceded the first Chinese-inspired interiors at the Royal Pavilion, but as complete design schemes they may well have inspired George to develop and change his Chinoiserie schemes in Brighton. For example, the large, red-ground paintings on the walls of the Music Room, which resemble lacquered surfaces, look like magnified versions of his sisters’ chinoiserie rooms in Windsor Park.

You could say that George not only embraced a feminine style, but he also “proudly” turned it up several notches, as you would in Brighton – then and now.