Shadows of Empire: The Calm of the Country House

First, though, our story pauses in the Morning Room at Preston Manor, from where Ellen directed her household. On the tour, we used this elegant, peaceful room as a place to reflect on the force required to conquer and retain the lands under British control. Colonialism was violent. Colonising powers also fought each other for control of lands rich in resources and people.

James Henry Green (1893-1975) took most of the photos of people in Burma/Myanmar featured in Shadows of Empire. He was a recruiting officer for the Burma Rifles, a regiment in what was called the British Indian Army or simply the Indian Army. Soldiers were recruited from across the British Raj, which included most of present-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Burma/Myanmar and Sri Lanka. Green’s role involved assessing people for their suitability to serve in the army.

In the British Raj (‘raj’ meaning ‘rule’), the British Indian Army drew up a prejudicial ‘martial races’ system. This categorised some ethnic groups and communities as suitable to serve in the army. Other groups were considered unsuitable.

Those thought suitable were perceived by the British as being from ‘warrior races’. The British believed they were braver and stronger than other ‘races’, and also less likely to rebel. This colonial tool was used to divide Indian communities, justify British dominance, and selectively recruit based on harmful stereotypes.

This racist system was dismantled when countries gained independence from British rule.

In India, this was in 1947. In Burma/Myanmar, this was in 1948.

One of the key figures in challenging and dismantling the racist recruiting system was Dr B R Ambedkar (1891-1956), the chief architect of the Indian Constitution. Dr Ambedkar advocated for social equality and the end of discriminatory practices.

In Britain, indirect taxes financed colonial exploits. And the costs of Empire could be high even for the wealthy and privileged. Ellen Thomas-Stanford was devastated by the death of her beloved grandson, Vere Benett-Stanford. He died in 1922. According to a memorial plaque at St Peter’s Church next to Preston Manor this was of a “sickness contracted on service” in the great clash between the world’s empires – the First World War (1914-1918).

It is estimated that around 2.5 million colonised people from colonies and dominions of the British Empire served in the First World War. Soldiers from India, Africa and the Caribbean were often conscripted to fight, others volunteered. Many colonial powers did not maintain detailed records of their colonial ‘subjects’ who served in the war.

Colonised people’s sacrifices were often marginalised or over-looked in historical accounts. Colonial powers also had political motivations to downplay the number of casualties among colonised soldiers. This makes it difficult to estimate how many colonised people died in the conflict.

Black soldiers from Africa and the Caribbean played a key part in the Allied victory. Yet they were barred from fighting on the Western Front, as the British government was concerned that Black men fighting alongside and against white men could undermine colonial structures. Instead, men from units such as the British West Indies Regiment fought in other parts of Europe as well as Egypt, Palestine and Africa (overseen by white officers). Black men were also used in non-combatant support roles. These ranged from digging trenches and burying the dead, to providing medical services.

In an attempt to ‘protect’ the British Empire, these Black soldiers were deliberately erased from history after the war. For example, Black men were excluded from the July 1919 victory parade past the newly built Cenotaph war memorial in London.

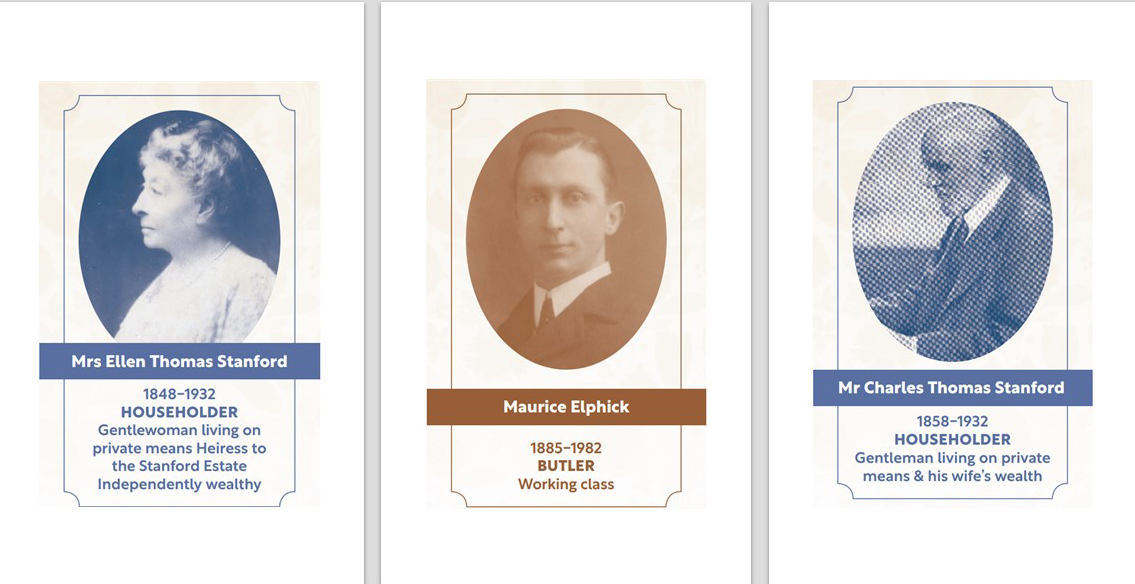

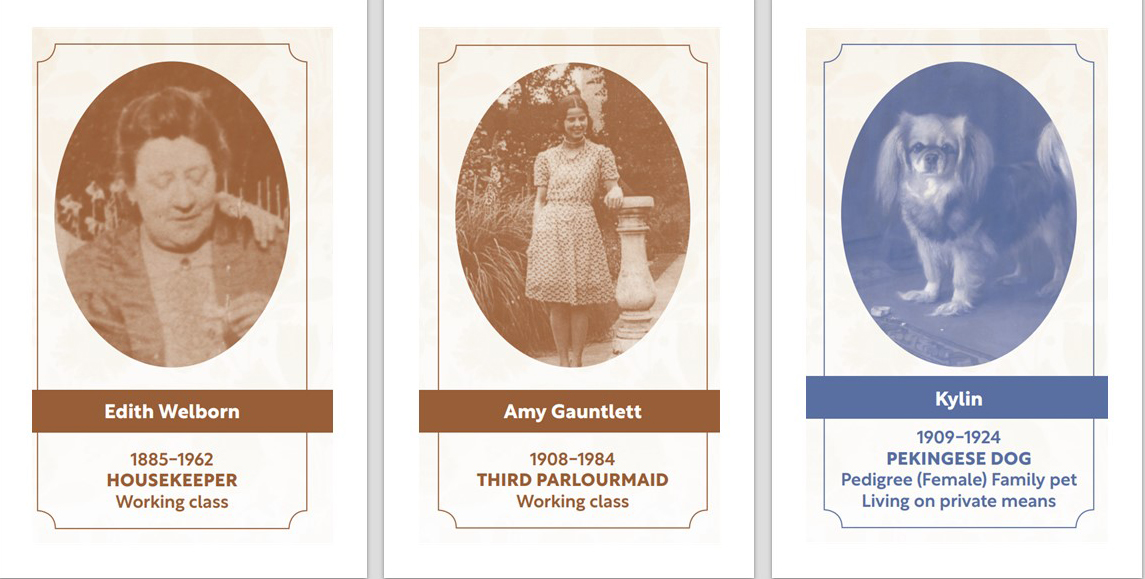

The strict hierarchies in some well-off Edwardian households can be linked to the broader colonial structures present in the British Empire. With their clear distinctions between different roles and levels of authority, the social structures of large houses mirrored the hierarchical structures prevalent in colonial societies.

In both contexts, there was a clear delineation of power and authority. People occupied specific positions based on factors like social status, wealth, sex and race. Colonial structures in the British Empire reinforced notions of superiority and inferiority among different groups.