Shadows of Empire: Spoils of Empire

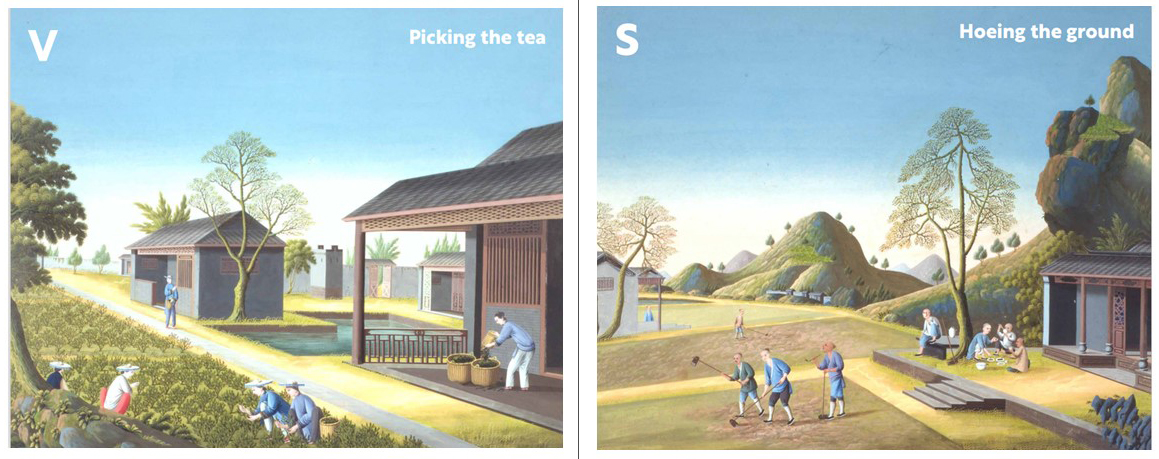

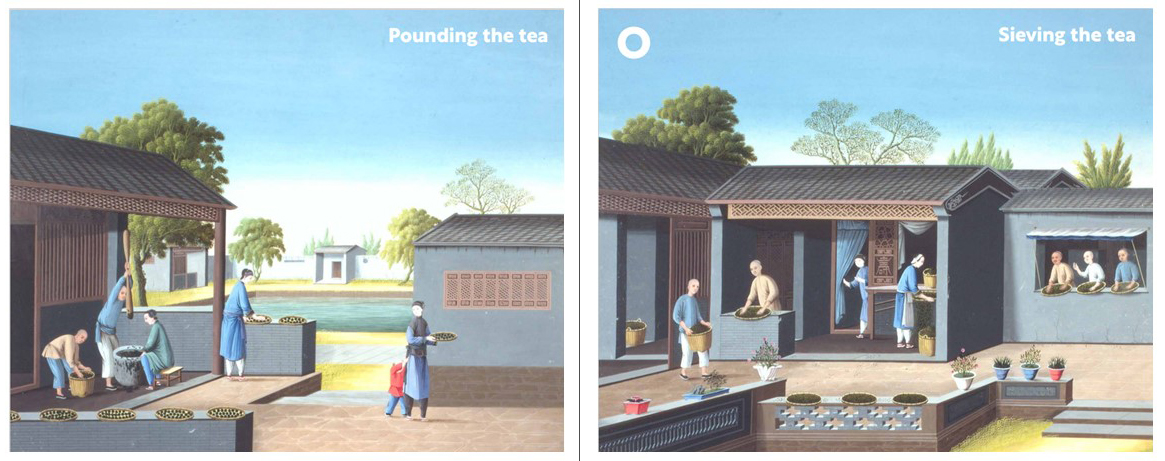

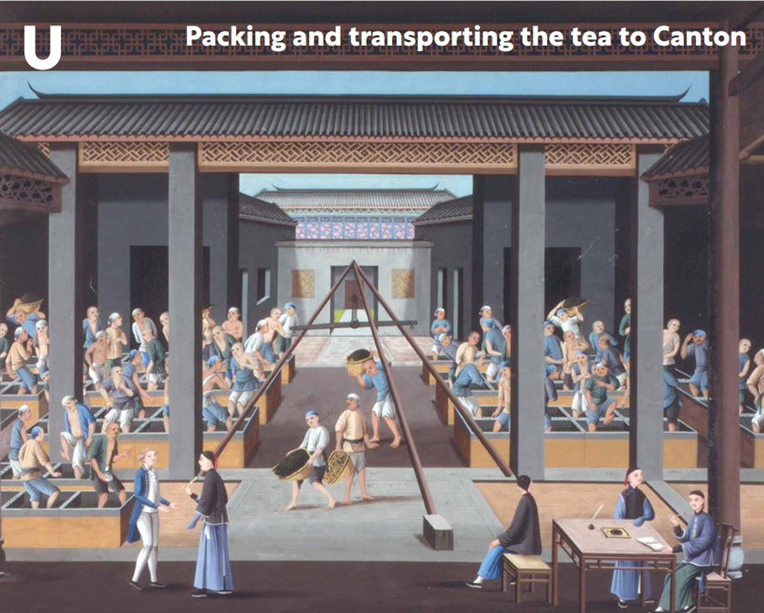

As Britain’s love affair with tea grew, so did its efforts to secure a reliable (and affordable) supply. In what has been described as the “biggest botanical heist in history” (Sarah Rose, author of All the Tea in China), the British East India Company sent Scottish botanist Robert Fortune on an undercover mission. In 1848, disguised as a Chinese merchant and explaining his halting Chinese by saying he was from a ‘distant’ part of China, Fortune stole not only tea plants, but also the Chinese people’s deep knowledge of cultivation and tea production, honed and perfected over the previous 2,000 years.

The tea plants and some of the experts in tea growing were transplanted to India, initially under the control of the British East India Company and then the British Raj (the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent from 1858 to 1947).

Conditions on tea plantations in the mid-19th-century were harsh and exploitative. Workers, who were primarily indigenous people or indentured labourers, faced long hours, low wages, poor living conditions, and limited access to basic amenities. They were subjected to strict rules and harsh discipline by plantation owners and managers.

With tea becoming ever more popular in Britain, the British East India Company still needed to source tea from China. But China wasn’t interested in Britain’s wares and would only accept payment in silver. In order to recoup some of the silver Britain had paid for tea, the British began smuggling opium to sell to Chinese people.

The opium came from plantations established in the British Raj. Men, women and children from various backgrounds were employed to work on them. The cultivation of opium was a lucrative industry for the British colonial government.

People working on opium plantations faced similar challenges to those working on tea plantations. As well as long hours, poor wages and poor conditions though, the sap from the opium poppies (called latex, containing the opium) could cause irritation and allergic reactions. Prolonged exposure to opium could lead to breathing difficulties and lung damage, affecting workers’ health and life expectancy.

We have in our collection an Edwardian “Opium Dream Machine,” which was originally token-operated. The moving figures depict a man smoking opium and his consequent hallucinations in the form of beautiful ladies and the devil. The figures are western stereotypes of Chinese people from the 1910s.

During the Edwardian era (from 1901 to 1910, but often considered to last until the start of the First World War in 1914), machines like these were popular forms of entertainment. They often showed scenes or figures that were intriguing as they seemed “exotic” to Edwardian Britons. This perpetuated harmful stereotypes and misconceptions about certain cultures. The portrayal of Chinese figures smoking opium in this ‘Dream Machine’ reflects the prevailing attitudes and perceptions of that era.

By depicting those who used opium as Chinese people, the ‘Dream Machine’ also ignored the fact that opiates were widely used in Britain and were easily available to buy over the counter for household consumption.

The Macquoid Room at Preston Manor is named after Percy Macquoid (1852-1925) and filled with antique furniture he collected. He was the husband of Theresa Dent, who bequeathed the collection in 1939. Theresa was a friend of Ellen Thomas-Stanford and a frequent visitor to Preston Manor.

Theresa Dent came from a wealthy family of opium “traders”. The family business was called Dent, Palmer & Co and had a fleet of opium clipper ships.

A glamorous portrait of Theresa Dent from 1883 hangs in this room, with a Chinese vase just visible behind her. Her luxurious lifestyle was a sharp contrast to the harsh conditions for the workers on opium plantations throughout the British Raj, who toiled to provide her family’s wealth.

There were significant consequences to the British smuggling of opium to China. The social impacts of widespread addiction and the economic effects of the steady loss of China’s silver reserves placed a severe strain on diplomatic relations between the two countries. The repercussions of this are explored later.