Return of The Thing: Tales of a Chinese ‘fire-pot’

Back in May, an unassuming grey ceramic pot, affectionately referred to by the collections team as ‘The Thing’, was removed from our off-site store by local Pyrotechnics company BrightFire Productions. The Thing was found during a routine check and was recorded as a ‘Chinese fire-pot or hand grenade’.

Upon discovery of The Thing, the World Art team immediately contacted external colleagues for advice on what to do with this potentially quite hazardous object and a decision was swiftly taken to remove the object from the store and have it decommissioned (rendered inert).

Although the pot clearly had something inside, at this stage the exact contents were unknown – it could have been filled with black powder (an early form of gunpowder), something more innocent, or something decidedly more offensive such as sulphur. The pot was completely sealed, and so without opening the pot we would have no way of knowing…

Mike Sansom, owner of local Pyrotechnics company BrightFire Productions and explosives expert, undertook the task of attempting to very carefully remove the central plug in order to find out what was inside. This was a complicated task, as The Thing was collected in 1852 in Shanghai, China, so Mike had to be as careful as possible not to damage the object. No drilling could be used (even a very small, fine drill hole) due to the potential fire risk of sparks and possible black powder.

The first task was to try and test what the plug was made of. By very carefully scraping around the edges of the plug it became clear the central plug was in fact ceramic and not something soluble or flammable. If the object is a hand grenade, this would be surprising as you would usually expect to see something that could be lit before you threw the pot, dissolving to allow the flames to reach the black powder inside.

Once the nature of the plug was established, the next step was to work out how to remove it. Mike did this by very carefully and methodically scraping around the edges to try and dislodge the glue that was used.

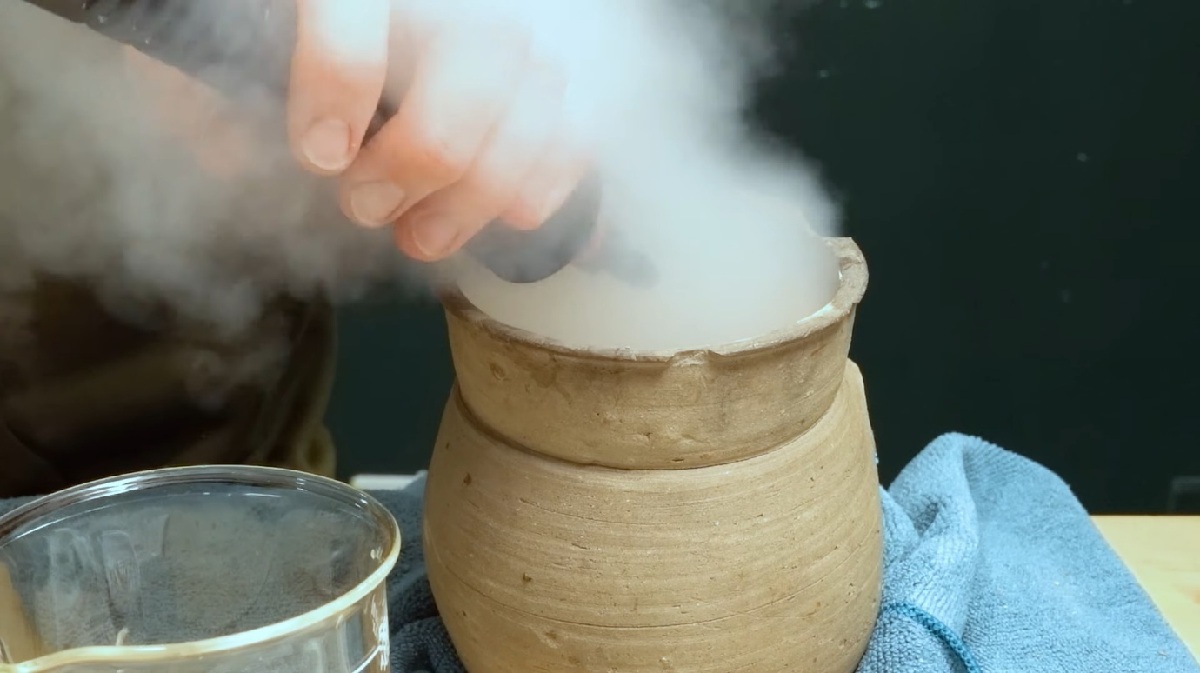

It became apparent that the glue was a very hard animal glue that was incredibly difficult to chip away, so steam was used to loosen it. After a lot of hard work and perseverance, the ceramic lid popped out of place, finally revealing the contents inside…

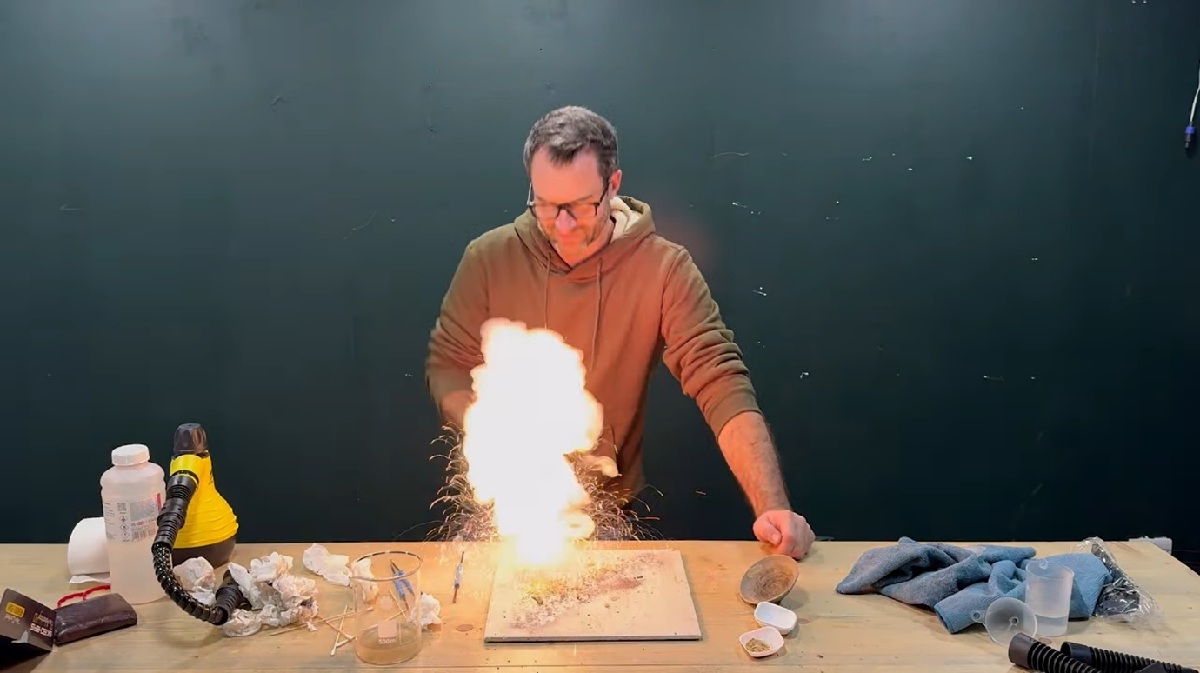

Around 850g of black powder has been sitting, un-touched, inside this small grey pot for at least 170 years. The black powder itself appears to be very early, possibly even 12th to 13th century. When comparing it to modern gunpowder it appears very crude, either made by an amateur or by an early process. From the way it burns, the look of the residue and the smell, Mike has roughly suggested a ratio of 73% Potassium Nitrate, 22% Charcoal and 5% Sulphur.

What makes the object even more fascinating is that it has been lined with a thick black glaze inside, which alongside the very solid animal glue sealing the lid, has made it incredibly waterproof.

The actual function of the pot is being widely debated. Colleagues at the Royal Armouries still believe it was used as a grenade – a fuse would be tied to the pot which would then be thrown, or alternatively the pot would be thrown into a fire. However, the amount of black powder in there would have burned too quickly to do any real damage to be used in this way and instead be more likely to have just created a significant amount of smoke.

Another theory is that it was a vessel used to transport the powder, and the lengths that were taken to waterproof the pot certainly support this theory. But to transport black powder in such small quantities is again quite unlikely.

So, we are still a long way from truly understanding what this object is and what it was used for, perhaps it was a small curio collected by travellers at the time? Maybe Western travellers bought small pots of powder to take home for use in fireworks (although unlikely as by this time the technology had already travelled overseas). Perhaps it simply was a hand grenade. Further work needs to be done to truly understand the object, and we hope to be able to do this in the future.