Finding James Henry Hubbard

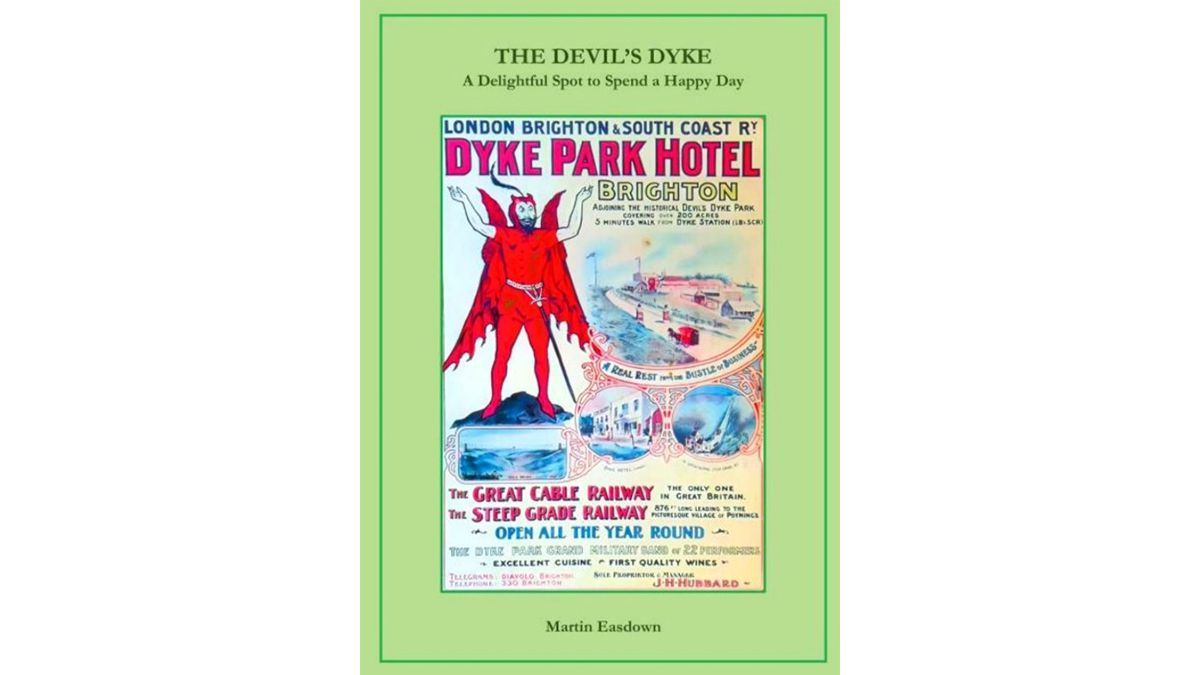

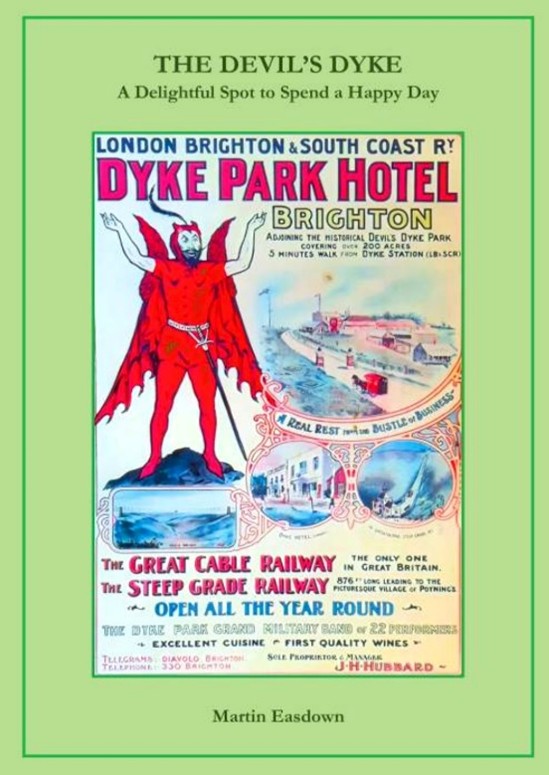

Local researcher and writer Sheila Marshall recently discovered a little-known history, hidden in the pages of a book, The Devil’s Dyke by Martin Easdown (available at Brighton & Hove Museums Online Shop). Her discovery fits perfectly with our Culture Change work to tell all of our stories, so we invited her to tell us a little more.

My background

I was born in Croydon in South London. Growing up, my parents encouraged and welcomed inclusivity. This was developed further at my girls’ grammar school in Nottinghamshire where classmates and a member of staff helped me broaden my social and political consciousness. This then led to me joining a women’s liberation group, joining anti-apartheid demonstrations during the Springboks South African cricket tour at sixteen and pushing for social change whether it be on the intersecting grounds of gender, race or class.

After living in London for a year, I went to study Philosophy with Psychology in Social Science at Sussex University and then moved to Brighton.

Living in Poynings

My first love was always nature, due to my father growing up in the Yorkshire countryside. After living in Brighton, I wished to be closer to the natural world. So, I moved to a tiny Tudor cottage in the village of Poynings, West Sussex. Once settled in Poynings, I quickly developed a passion for both local history and craft – later appearing in the Meridian TV Countryways series, ‘The Devil’s Dyke in October’.

I spent much time researching and interviewing local people, together with neighbouring villager Steve Poyntz, who shared my interest. After speaking with the local elders of Poynings (nearly 50 years ago now), they were keen to highlight the massive impact that the ‘tourist attractions’ Devil’s Dyke in the early 1900s had had on the village. They told of the steep grade and Devil’s Dyke railways and how the hillside was often “black with people”, there were so many of them! They also told me how four or five tea gardens had sprung up in Poynings alone to receive the huge number of visitors – a particularly large one at the Royal Oak Hotel.

Our intention had been to write a comprehensive history of Poynings but all I achieved, a few years later, was our research condensed into two sides of A4 for the first village website.

The revelation of reading Martin Easdown’s book, ‘The Devil’s Dyke: A Delightful Spot To Spend A Happy Day’ was a delight. I was amazed to discover that James Henry Hubbard, who was behind the most notable of the attractions at the Devil’s Dyke from 1891-1904, was in fact the mixed-race son of freed Virginian enslaved people. Also, his brother William Peyton Hubbard was one of the first Canadian statesmen of African descent and a minority rights campaigner. Like most people in the village, I had always imagined James to be some ‘Great white hunter type’* and thus had little interest in him.

Getting it out there

I just couldn’t believe the fact that James was Black had never been mentioned by either the local villagers that I had spoken to, nor mentioned in any of the numerous pamphlets about the Devil’s Dyke.

Driven by the desire to right the wrong of James Hubbard’s family background being hidden from history, I was determined to spread the news to the appropriate organisations. I contacted Brighton & Hove Museums, Brighton & Hove Black History, The National Trust at Saddlescombe Farm and Sussex University all of whom were very enthusiastic.

The second edition of Martin’s book

After being in constant dialogue with Martin around James, we quickly became friends. I encouraged Martin to bring out a second edition of his book and both Steve Poyntz, Alan Barwick (from Henfield) and I provided him with some pictures and extra information for it.

My history of Poynings book

Martin has in return encouraged and offered to help me to complete my book on the history of Poynings.

* ‘Great white hunter’ is associated with the exploitation of Africa by White European men on big-game hunts especially during the first half of the 20th century. This trope gained significance in Western art, literature and popular discourse, painting the colonial pillager as a romanticised adventurer and hero.