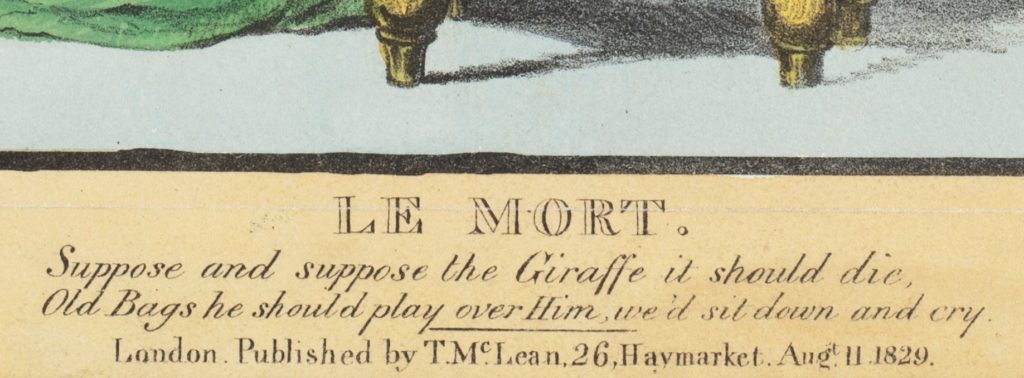

Dissecting a Giraffe Image: John Doyle’s Le Mort, 1829

This is a legacy story from an earlier version of our website. It may contain some formatting issues and broken links.

Today, 21 June, marks World Giraffe Day. To celebrate we look at a print of King George IV’s very own giraffe.

This caricature by John Doyle, titled Le Mort from 1829 shows the king, George IV, accompanied by other figures, crying over a dead giraffe, which is lying dramatically on her back on the ground, legs in the air, and her head resting on gold-fringed cushion. What is the story behind this?

Le Mort, John Doyle; Thomas McLean; Joseph Netherclift 1829 © Royal Pavilion & Museums Brighton & Hove

Although exotic wild animals and birds had been around in European menageries since the middle ages (there was, for example, a polar bear in the menagerie in the Tower of London in 1252), giraffes proved to be the most elusive and unusual of wild animals. Impossible to catch or tame as adults and of such fragile build that even the transport of a young giraffe mostly ended in the death of the animal, this strangely shaped and curiously beautiful creature captured the imagination of pre-Darwinian society.

The giraffe in this print was a real one. The female specimen arrived in London in the summer of 1827 and was the first living giraffe to have reached England’s shores. She was a diplomatic gift from Muhammad Ali, Viceroy of Egypt. He gave a second giraffe to Charles X of France, and a third to the Emperor of Austria. Each giraffe had two Egyptian milk cows, two Egyptian keepers, several other African mammals, and a translator for company on their journeys to Europe.

Wearing you hair ‘a-la-giraffe’ in the late 1820s.

Several beautiful images of the giraffe were created after her arrival, but critical caricatures depicting the giraffe greatly outnumbered these. To be fair, the caricaturists poked fun at George IV more than the giraffe. The giraffes’ arrivals in England, Austria and France sparked a new fashion coined ‘giraffe-mania’, which resulted in yellow becoming a favourite colour in women’s fashion and home-furnishings, and many decorative items, such as fans, candle-holders, and even cakes, music, hairstyles and wallpaper were inspired by the exotic creatures.

A weeping lady

The seated figure next to George is his last mistress, Lady Conyngham. From 1827 George spent much of his time with her at the Royal Lodge in Windsor Park and never returned to the Royal Pavilion. He kept his giraffe at his private menagerie at Sandpit Gate in the Park and together they visited her almost every day.

The seated figure next to George is his last mistress, Lady Conyngham. From 1827 George spent much of his time with her at the Royal Lodge in Windsor Park and never returned to the Royal Pavilion. He kept his giraffe at his private menagerie at Sandpit Gate in the Park and together they visited her almost every day.

George IV at Sandpit Gate, his private menagerie at Windsor Great Park, late 1820s.

After George’s death Lady Conyngham was depicted by cartoonist William Heath as taking precious things with her when being kicked out of Windsor Castle. Among these was the skeleton of the giraffe, which was considered extremely valuable. This didn’t really happen but shows how rare giraffes still were at the time, even dead ones.

Who is the man with the bagpipes?

The man with the sad face, playing a mournful tune on the bagpipes, is Lord Eldon, who had been Lord High Chancellor under George III and George IV. In the accompanying text the elderly statesman is disrespectfully referred to as ‘old bags’. A pill box and a medical prescription can be seen next to him, which could be for Eldon, George, or the giraffe. They are all in a sorry state. George was frequently criticised for putting his own pleasures and toys (such as the giraffe) before his duties. Here is the King of England crying over a dead giraffe instead of looking after the wellbeing of his country and people.

Bandaged legs

The giraffe suffered badly from injuries sustained on the long journey from deepest Africa to Windsor. In the months before her death she was unable to stand and a giant frame with a sling was constructed to hoist her up. In the summer of 1829 the naturalist James Rennie reports the state of the giraffe in volume 1 of his book series The Menageries:

[pullquote align=center]

From the period of its arrival at the Menagerie at Windsor Great Park to the present time (June 1829) the animal has grown eighteen inches. She can now reach about thirteen feet. Her usual food is barley, oats, beans (which are split), and ash-leaves. She drinks milk. Her health is not good. Her joints appear to shoot over, and she is very weak and crippled, affording little probability that she will recover her strength. She is occasionally led for excercise round her paddock, when she seems well enough; but now, in the day, she is seldom on her legs. Indeed, so great is the weakness of her forelegs, that a pulley has been constructed, being suspended from the ceiling of her hovel, and fastened around her body, for the purpose of raising her on her legs without any exertion on her part.

[/pullquote]

A double-page from James Rennie’s The Menageries, vol 1, showing an image of George’s giraffe.

The bandaged legs here are a also reference to George’s troubles with gout and other ailments. Earlier caricatures showed him with bandaged legs, unable to mount his horse unaided. Both the ageing and ailing George and the giraffe were great fodder for caricaturists.

Was the giraffe dead yet?

In John Doyle’s Le Mort the death of the giraffe is anticipated, as the print was actually published two months before the creature’s demise. The giraffe is wrongly assumed to be male in this print. The public was critical of the costs incurred by the giraffe, for example, whether the taxpayers would pay for having her stuffed. The giraffe was dissected and stuffed by the talented young taxidermist John Gould.

The Times reported in April 1830: The stuffer to the Zoological Society, Mr. Gould, has had the performing of his duty [sic]…Soon after the giraffe expired, De Ville, the modellist, was ordered down to Windsor, by His Majesty, and took a cast of the animal. From this cast a wooden form was manufactured, on which the skin of the animal is now placed, and which preserves its beauty in an extraordinary degree.

It had been George’s intention to donate the stuffed giraffe and her skeleton to the people. His successor William IV formally presented both the skin and bones to the Zoological Society of London’s museum in August 1830. We don’t know where her remains are now, but I am still looking for her, with the help of a couple of other giraffe-enthusiasts.

Alexandra Loske, Curator, Royal Pavilion