Decolonising the Natural History Collection at the Booth

Decolonisation is a priority in western museums at the moment. Having acquired material from around the globe, organisations now seek to balance the stories presented to give a more equal voice to all those involved, as well as correcting the power imbalance inherent in colonial practices.

Whilst the focus has been on collections more intricately linked with global cultures, natural history collections also have a part to play. This is both directly, in terms of human remains, and indirectly in the language historically used in describing and classifying the natural world and naming species new to western science.

Repatriation – the long road home

Smaller museums such as the Booth, are less affected by some of the more controversial aspects of decolonisation, such as repatriation of early human remains to their country of origin. (For example, current efforts by Zambian scholars to have ‘Broken Hill man’ renamed ‘Kabwe man’ and returned to Zambia from the NHM London). However, our collections do contain specimens from around the world. Many of these have no record of how they were collected, but some can be assumed to have been acquired by less than reputable means.

These include the remains of a ‘Japanese monk’ in a burial urn. Recent work by a human osteology specialist, noted that these remains are highly unlikely to be of Japanese origin, as the urn was purchased in Hong Kong, in the mid 1800’s during a period when it was a capital offence for Japanese citizens to leave Japan.

Examination of the skeleton showed that the person in the urn had suffered an injury to the back of their leg, likely from a threshing machine, indicating they were a farm labourer rather than a monk, and that they lived long enough after this injury for it to heal. It was the conclusion of the researcher, that this was likely a poor Chinese peasant who had died and was placed in the Japanese urn to sell to the English forces and colonists in Hong Kong following its occupation during and after the Opium wars.

Specimens such as the one detailed above remain in store, awaiting repatriation requests, as there is no straightforward way to determine who it would be offered back too without expert review, research and potentially using equipment well beyond our budget.

However, the museum has worked to resolve repatriation requests when received. This included the return of Australian aboriginal human remains, which were part of F.W. Lucas’ Museum, transferred to Brighton Museum in the 1920s. These remains were requested for repatriation from representatives of both tribal communities and the countries governments, and were handed over to representatives of the Ngarrindjeri Community, on Friday 15 May 2009, at a ceremony in the grounds of the Royal Pavilion (Other remains followed in 2016).

Local names for local creatures

One area where we have more agency to progress changes is in the recognition that the language used in describing the natural world has traditionally been biased towards a western colonial viewpoint.

There are some aspects which cannot change as they are internationally recognised. So, for example, the use of Latin names for the scientific naming of species was decided on specifically to avoid upsetting the various European powers in the 1700s. Latin was chosen as a dead language, so as not to give preference to French, English, German, Russian or Spanish as the dominant powers of the period.

However, the common names of species were decided upon by the native language of those describing the species for the first time, and usually reflected either the colonial power of that country, the ‘discoverers’ native language, common parlance of colonial settlers or the supposed peculiarities of the native culture present where these species lived.

The last of these can prove particularly problematic today, when tied to racially offensive language. Examples of this include the sour fig which was previously known as the ‘Hottentot fig’ – this is a derogatory term for the Khoi people and is no longer used.

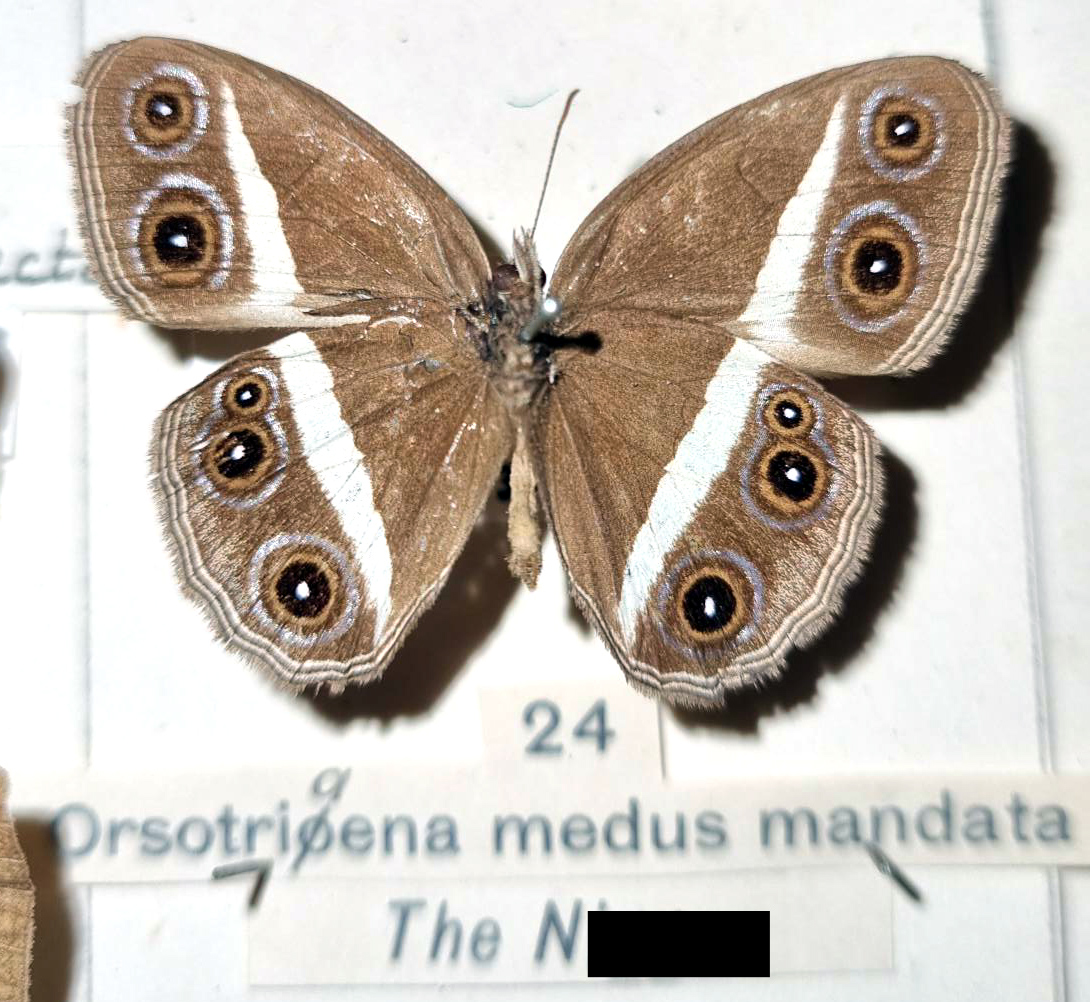

Even more problematic is the butterfly Orsotriaena medus, which is a dark brown butterfly found in Southeast Asia and Australia. It was originally given a common name that is now regarded as highly racially offensive – a common name now rightly not used in museums or the wider scientific community.

Even when common names are not necessarily racially offensive, they do still overwrite the names these animals are known as in the native cultures. One place this is particularly prevalent is in Aotearoa New Zealand. Much like the country’s name, the animals on the islands were given western common names by the British invaders of the Islands. This resulted in the birds being given names such as Owl Parrot, Stitch-bird, Parson-bird, and Bellbird. These names were written on the old labels and the stands on which the taxidermized birds are mounted.

Taking the lead from their country of origin, as well as bodies such as the International Ornithologists Union, we have renamed our specimens from Aotearoa NZ to reflect the Maori names these animals were originally given.

’Owl parrot’ is now referred to as Kākāpō and ‘Parson birds’ are now known as Tui. This renaming of species to a recognised local name also helps iron out some confusion when it comes to common names. The korimako, known to western settlers as the New Zealand Bellbird, is unrelated to the bellbirds of South America. South American bellbirds are part of the cotinga family, whist korimako are part of the meliphagidae, the Australian honeyeater family.

That the animals from these geographically isolated regions were last to be known to western cultures, is also reflected in how they are described.

Jack Ashby at the Museum of Zoology, Cambridge, has previously given talks on how animals such as echidna, platypus and the other highly diverse fauna and flora that has evolved in Oceania has routinely been described in western media, popular culture, and museums with terms such as ‘weird’ ‘primitive’ ‘strange’ or ‘bizarre’.

These terms help reinforce the perception that animals from Europe and America are the norm and are more highly evolved. This ignores the fact that if you and your culture come from somewhere like Australia, these species are not unusual, but introduce these people to a cow or camel (both now common in Australia) and they would be perceived as weird and unusual. The ‘primitive’ descriptor is possibly the most harmful of these terms, as it incorrectly surmised the animals here have evolved less than placental mammals, and that the continent was more backwards than Europe (reflected in colonial derision of traditional Aboriginal hunter gatherer society). This ignores the fact that all animals currently alive have evolved to the level required to survive in their environment, meaning an egg laying monotreme is no more primitive than a great ape giving birth to live young.

Following Jack’s talk, we reviewed our labelling referring to Australian fauna and, thankfully, problematic terms had been avoided. However, as part of our decolonisation culture change, it is planned to put this in as policy to avoid belittling and ‘othering’ cultures outside of our traditional Western bubble.

These processes are not without problems though. Renaming Aotearoan birds to the Maori names is a straightforward process, as along with consensus in using the Maori names, there are no competing names to deal with (outside of colonial ones). It is when you move to other parts of the world where a species might be found in several diverse and distinct cultures across a number of countries that picking a different common name can be problematic. Replacing the common name of the Orsotriaena medus is a prime example. Australian scholars have renamed it Bush brown, whilst in India it is renamed medus brown and in Southeast Asia, it is called the dark grass-brown. So, which of these names do we choose?

Even more problematic is when a local name might come from a culture who do not traditionally differentiate between species. An example of this comes from conversing with my Malaysian relatives. The local name for the palm civet is ‘musang’ – seems straightforward to change the name of our specimens to musang right? However, the problem arises when you then realise that musang can also translate to ‘fox’ an entirely different small predatory group of mammals.

Ghost Collectors

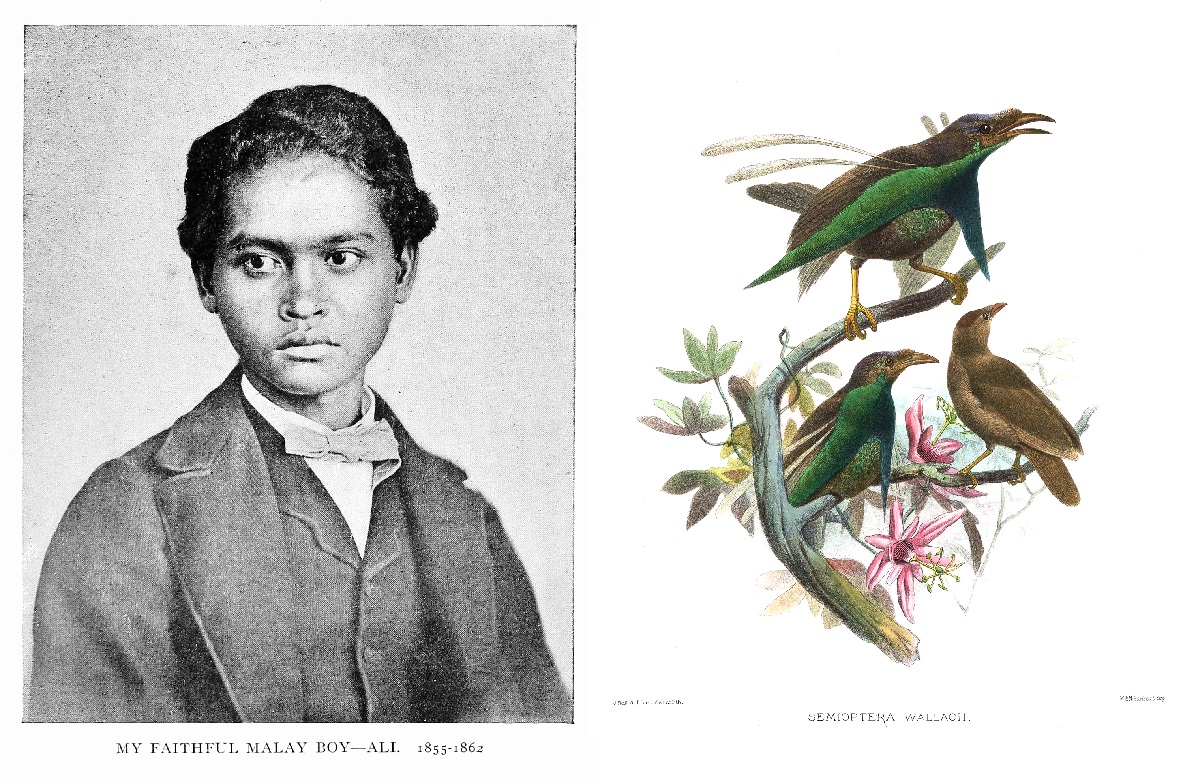

There are also problems drawing out stories of those hidden by history. Looking at the collections you would be forgiven for thinking these were all collected by white upper-class Englishmen on expedition to far flung corners of the world. But take a closer look and you will find evidence of all those who helped build these collections.

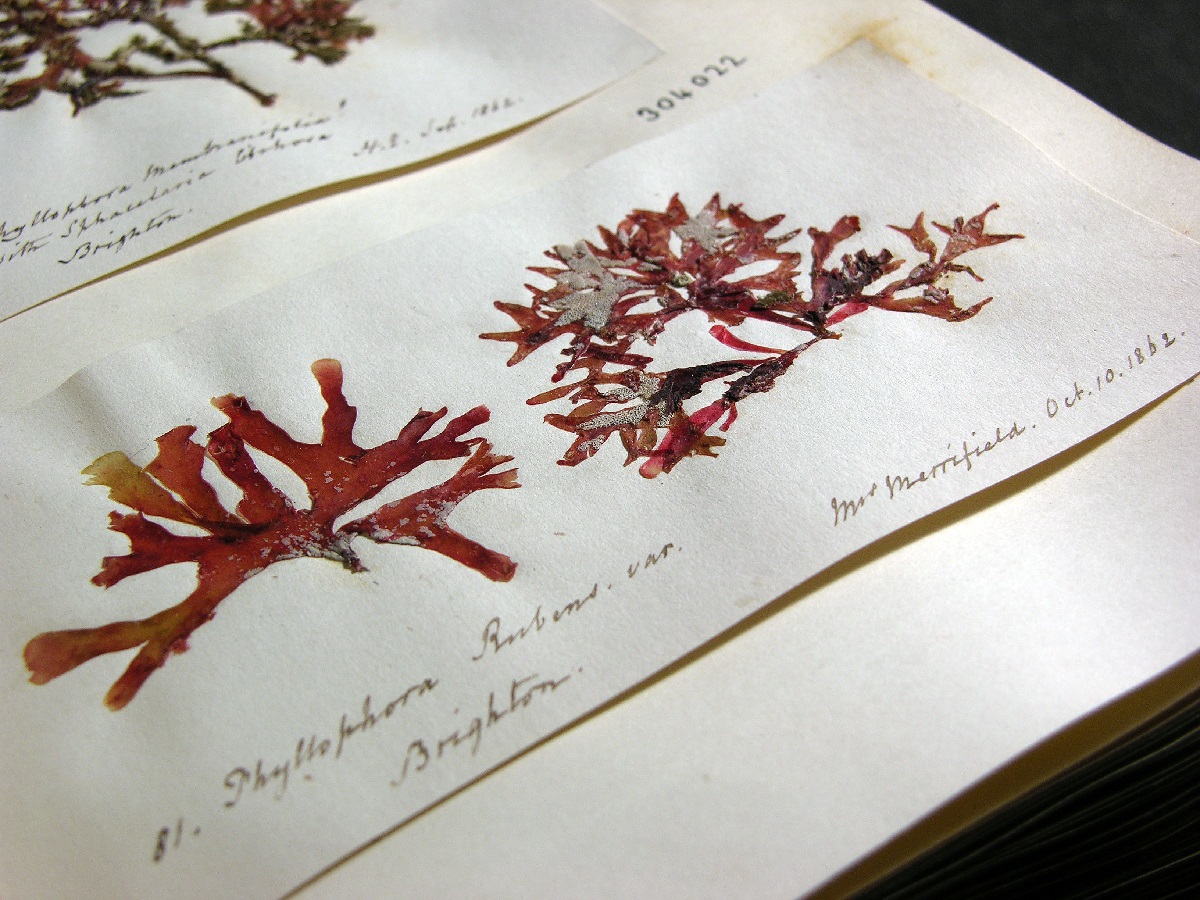

They may be women who are obscured behind their husbands’ names (our collections include seaweeds assigned to Mrs Leopold Grey for example – her first name is not recorded, only ‘Leopold,’ her husband). Or it may be the countless locals involved in collecting specimens. The problems drawing out these stories are that very few details were recorded about these people, so it is hard to give much individualism to their stories (one of our entomology collectors, Oberthur’s, insects include hundreds of specimens collected by ‘indigenous hunters’ in Nepal, which were then provided to Missionaries, who in turn passed them onto Oberthur).

These are elements which will need to be discussed both internally and with external partners and demonstrate how complex decolonisation can become.

As complex as it may be though, it is important to do this work to make sure these specimens are accessible to as many people as possible, and that at the very least we can ensure future interpretation of these collections indicates the many people involved in building the collections, and not just the ‘colonial master’ at the top.

It is important that a global community feels like these collections belong to them and are important to them. Because if people do not care about things, they have no reason to save them, and many of these communities exist in areas on the frontline of climate change and environmental destruction.