Agnes Crane, Queen of Brighton’s Brachiopods – Later Life and Legacy

Agnes Crane was a scientific lecturer and writer who was a key person in the development of Brighton & Hove Museum’s natural history collections, specialising in brachiopods. We pick up her story from the previous blog post post – Agnes Crane, Queen of Brighton’s Brachiopods.

Her father Edward Crane had died in 1901, he “… passed suddenly away from heart disease of long standing”. He had already resigned his Chairmanship of the Brighton Museum Sub-committee due to ‘increasing age and deafness’ but continued to be interested in scientific literature until the end. Jane Crane, Agnes’ mother, died only a few years later, on 8 Feb 1904. The grief at the loss of both her parents seems to have affected Agnes’ health. There is correspondence from Agnes to scientists in the Natural History Museum, London, preserved in their library, which sheds significant light on her life at this time. Dated 30 July 1915 she wrote to Francis Bather from St. John’s Lodge recording her sending him a spare copy of her paper on Brachiopoda,

We do not know the nature of her illness. In fact, despite her somewhat pessimistic message, Agnes lived until 3 July 1932. However there is little evidence of any writing or research activity at this time. Her death certificate records the cause of her demise as jaundice, biliary obstruction, gall stones and uterine fibroids. Her estate was valued at £8,676, worth the equivalent of £775,000 today. Probate of her 9-page will of detailed instructions was granted to the Public Trustee. The majority of her instructions relate to specific gifts to people and organisations, mostly sums of money and books. However, early in her instructions she writes:

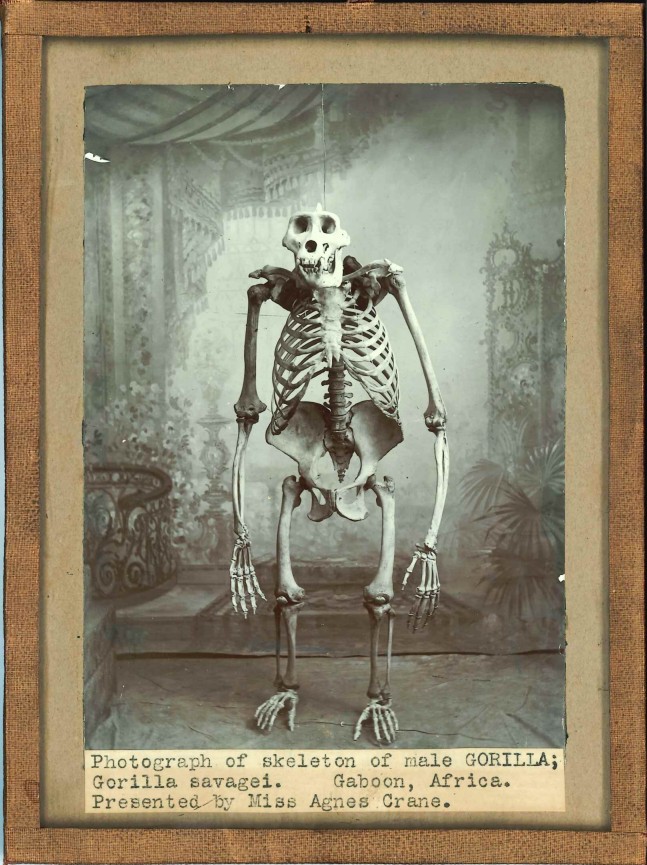

To the Corporation of Brighton for permanent exhibition in the Public Museum the framed plaster cast of the fossil bird Archaeopteryx and such of my collections of fossils and minerals osteological and archaeological specimens as they may select…

These donations can still be found in the collections of the Booth Museum and Brighton Museum & Art Gallery.

One further interesting piece of social history emerged from her will which asked for her

“… ashes to be placed in a terracotta urn with my name and age inscribed on a brass tablet affixed thereto and placed by the side of the urns containing the remains of my late Father and Mother now deposited in plot 458 under the family monument in the grounds of the Cremation Society of England at St. John’s Woking Surrey…”

Cremation of the dead was not a practice known or even legally available to the British public until late Victorian times. Its main promoter was Sir Henry Thompson, a surgeon and physician to Queen Victoria who had seen modern methods of cremation at an exhibition in the Vienna Exposition in 1873.

Impressed, he made a strong case for its adoption in the UK, arguing that it was a more sanitary solution for the respectful disposal of dead bodies, suited to a growing population, and less expensive and more convenient than burial. With others, he formed the Cremation Society of Great Britain in 1874 and founded the UK’s first crematorium in Woking. After some legal objections were cleared, the first official cremation took place in 1885.

The cremation of Agnes Crane, and her parents before her, clearly reflected a deep-seated acceptance of the principle of the process. Staff at the Woking Crematorium have confirmed that plot 458 holds the granite monument on which are inscribed the names of Edward Crane, Jane Crane and Agnes Crane.

But despite all of the research done, we haven’t identified an image of Agnes Crane herself and still don’t know why the gorilla skeleton was photographed against such a domestic backdrop… if anyone has a suggestion, we would love to know.