African Beasts in British Cabinets: The Complex History of Animals in Museums

Giraffes, gorillas, and gazelles – many of the most iconic animals on display in European natural history museums originally came from the African continent during the height of the colonial era. But how did these animals end up in Western collections, and what does their presence really represent?

Though the Booth Museum of Natural History in Brighton was originally set up purely to exhibit British birds, Brighton Museum had wider natural history collections, which were moved to the Booth in the 1970s. Like many such institutions, Brighton’s collections include African animals. But few museum signs or plaques discuss the often-troubling history behind how these specimens were acquired.

During the ‘Scramble for Africa’ in the late 19th century, European powers divided up the continent, claiming large swaths as colonies. Alongside seizing land and resources, Europeans also collected African animals at an unprecedented scale.

Hunters working for museums shot thousands of animals and shipped their skins, skeletons, and even whole specimens back to Europe. Many species were driven close to extinction by overhunting for museum collections.

For example, European hunters decimated elephant populations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Whilst most were shot to supply ivory to craftspeople making trinkets (many of which later ended up in museums) many were also shot for museums. The African elephant population has now declined by over 90% since the 19th century. Many elephants were shot simply for their tusks, with the rest of the carcass left to rot.

Giraffe specimens were in high demand from museums and private collectors, due to their rarity in Europe at the time. Giraffe populations declined sharply due to overhunting, with thousands shot just for their skins and skeletons. Two skulls in Brighton’s collections come from the private collection of F. W. Lucas, who bought his specimens at auction. It would be a mistake to think that giraffes aren’t a species we need to worry about, though our familiarity with them might make us believe they are ubiquitous. In fact, giraffes are now listed as ‘vulnerable’, with two subspecies being ‘critically endangered’.

All five species of rhino were targeted by hunters supplying horns to museums and collectors. By the early 20th century, several rhino species had been driven to near extinction. Only intensive conservation efforts have brought some populations back from the brink.

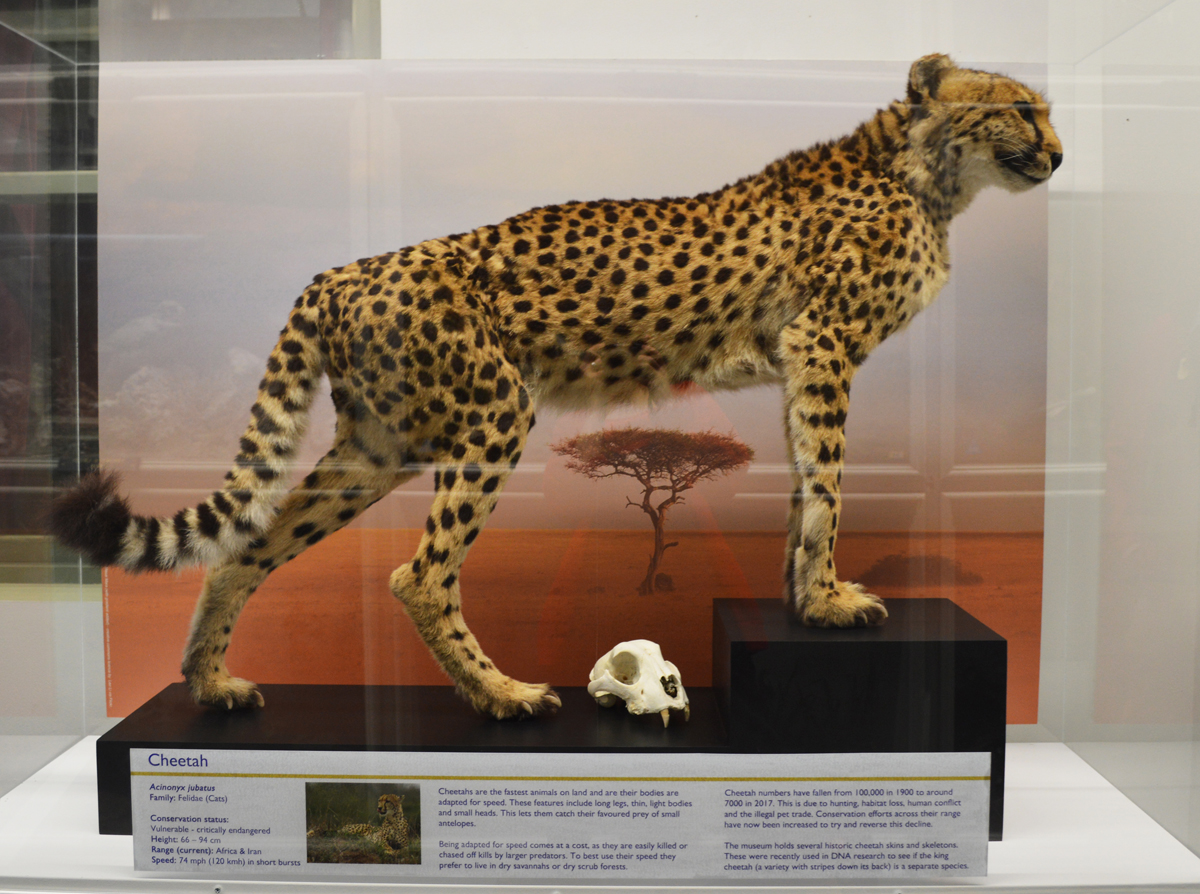

At the Booth Museum, we have a tiger trophy head shot by English ‘gentleman hunters’ in India. Lions, leopards, and cheetahs were intensively hunted for their skins and trophies, both for private collections and museums. Their populations declined significantly across much of Africa during the colonial era. Many museum specimens were obtained by paying professional hunters to shoot the animals.

These ‘big game’ trophies are also supplemented by large collections of animals collected for science, but with little regard for conservation. These include pangolins, butterflies, tortoises, lemurs and primates including chimps and gorillas.

For Europeans at the time, displaying African animals was a way to assert their dominance and superiority over what was once called the ‘Dark Continent.’ The animals came to symbolize what they believed was Europe’s colonial mastery over nature itself.

But today, exhibiting African animals without acknowledging this history feels disrespectful. The Booth Museum is making a start by being more transparent about how our collections came to be.

Today, the Booth Museum and Brighton’s natural science collections only take in modern specimens which have been ethically sourced. These are animals which are found dead by members of the public or which are the unfortunate victims of road collisions, window fatalities or cats. We only commission taxidermists who work with the same ethical considerations, so we can be sure anything commissioned is also from ethical sources.

Our collecting policy also reduces what we collect to items from Sussex or Sussex-based researchers, meaning modern specimens will not be the result of hunting or tourist trophies from Africa or other overseas locales. ‘Exotic’ species such as cheetahs or tigers that have entered the collections more recently are ex-zoo specimens. This includes Boris, our teaching tiger skin specimen, and the cheetah mounted specimen at the front of the museum, both of which were zoo animals put down due to illness in the 1980s.

As we walk through museum exhibitions today, filled with wonders from across the globe, we must not forget the dark history of how many of these specimens arrived in our cabinets. Countless animals were killed and transported across oceans, without regard for their lives or habitats, all for the sake of human curiosity and entertainment.

We have become more ethical and aware in recent times, but we cannot change the past. The least we can do is show respect for those animals that died to further our knowledge and resolve to do better going forward. Their sacrifice can serve as a reminder of our capacity for both cruelty and compassion and inspire us to choose the latter as we explore the natural world.