Agnes Crane, Queen of Brighton’s Brachiopods

Guest blog from John Cooper – Keeper Emeritus of Geology, volunteer at the Booth Museum on rediscovering Agnes Crane (1853 – 1933), a museum worker of distinction.

Part one:

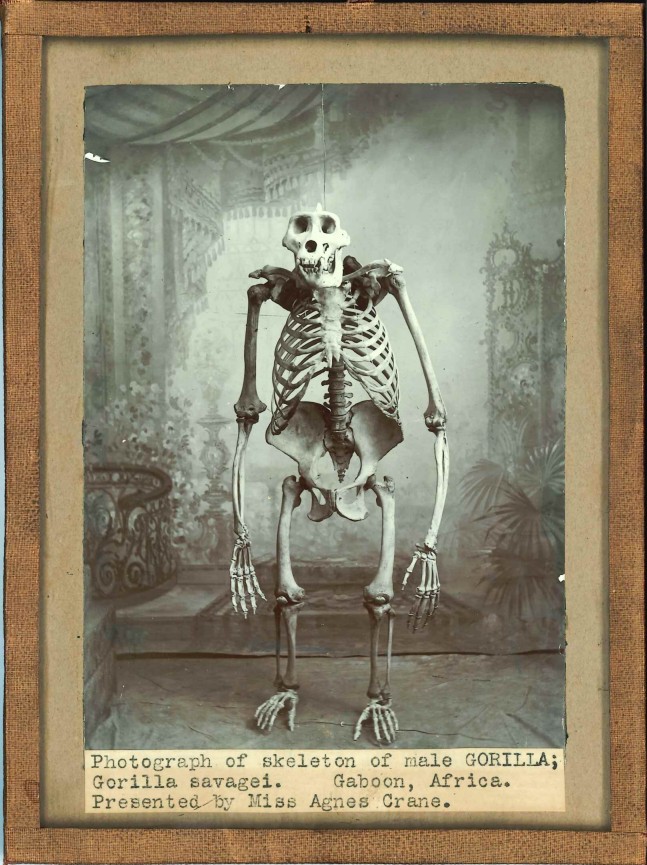

In the back rooms of the Booth Museum in Brighton there is a photograph of a gorilla skeleton, taken against a backdrop of drapery and plants typical of those used in Victorian photography studios. A typed note explains that it is a “Photograph of skeleton of male GORILLA; Gorilla savegei. Gaboon, Africa. Presented by Miss Agnes Crane”.

There wasn’t any context for the photo, or any other details connected to it, but the slightly odd photograph did get us wondering who Miss Agnes Crane was.

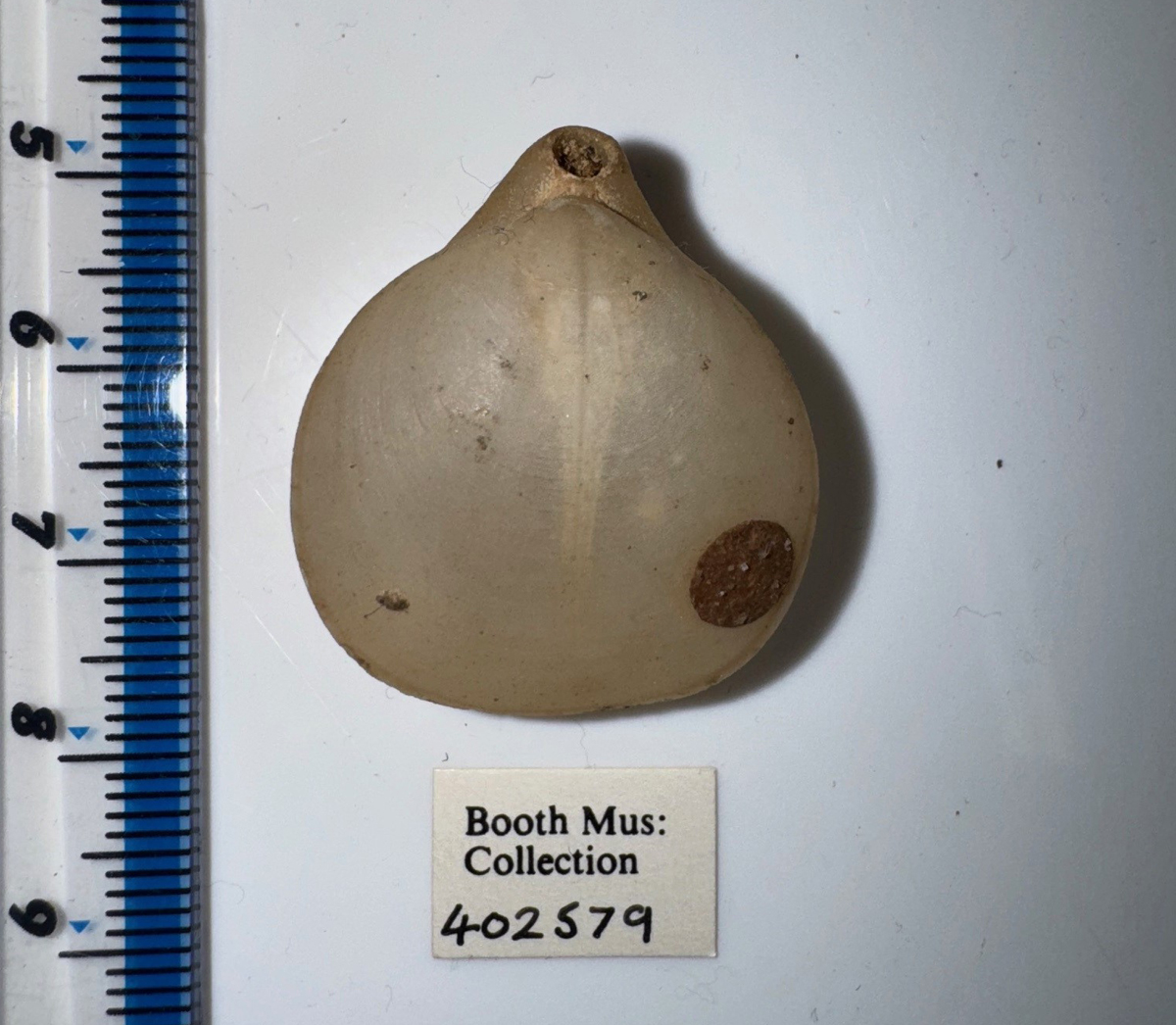

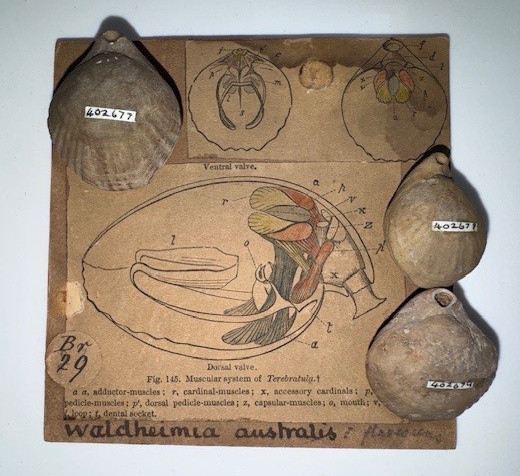

So, the team at the Booth looked for her in the records and discovered a collection of fossils linked to a woman called Agnes Crane. Many of the fossils are a type of marine shellfish called brachiopods.

We are always keen to find out more about the people in the past who collected the objects held in the museum today. John Cooper started to investigate Agnes Crane (1853 – 1933), starting with the documentation we hold at the Booth Museum.

The paperwork revealed two major Brighton Museums connections with Agnes Crane.

Her father Edward Crane (1822 – 1901) was a significant figure involved with Brighton Museums in the later nineteenth century. He was especially involved with scientific matters. For many years he was Chairman of the Museum’s Sub-Committee. Women were not encouraged to be part of these committees, but wives and daughters were often coopted into working voluntarily on museum and scientific collections if they showed an interest in the subject matter.

The museum papers revealed that Agnes Crane worked alongside Thomas Davidson (1817-1885), a famous palaeontologist whose specialty was in the brachiopods, and who lived in Brighton from at least 1871. Described as ‘an old friend’ of Agnes’ father, Thomas Davidson was Chairman of the Museum’s Sub-Committee before him, retiring in 1875.

But we wanted to know more about Agnes Crane herself. John started his wider research – and this is what he discovered…

Agnes was born on 9 April 1852, the only child of her parents, Jane (née Turnell) and Edward Crane. Edward was a tenant farmer on the Duke of Bedford’s estate in Thorney, east of Peterborough, Cambridgeshire. The 1851 census records Edward Crane as a farmer of 206 acres employing 25 labourers, living at Little Knarr Fen, Thorney. He and Jane married in the same year, with Agnes born 9 months later.

We don’t know how Edward acquired an interest in science, perhaps through his agricultural upbringing, but it was certainly an interest he later passed on to his daughter.

The 1861 census records the Crane family at the same address but without little Agnes. Instead, she appears as a visitor to a family in Islington at the age of 9. Her entry in Who’s Who (1911) states that she received her schooling in London, which explains her absence from the family home.

Edward retired in 1866 at the young age of 44. His father Wright Crane had been a landowner in the area and became quite wealthy. This presumably meant that Edward, Jane and Agnes were able to live off independent means. The Crane family travelled a great deal together – initially around Europe, before settling in Brighton in 1867. They bought a house in Wellington Road called St. John’s Lodge at number 23 and the family can be traced there through the census records from 1871 to 1911.

Agnes and her father later travelled extensively in North America, Cuba, and Mexico, as well as further journeys in Europe and the British Isles. Agnes developed extensive contacts in the field of natural history as well as making many friendships on her travels, which must have given her plenty of inspiration as her communication skills developed.

In the census record for 1881, at the age of 28, Agnes Crane’s occupation is recorded as ‘scientific lecturer’. By this time her father had become active in the Brighton museum scene, being involved in the transfer of the budding Brighton Museum’s removal from the Royal Pavilion to its present site the other side of the Pavilion Garden. Edward became a Fellow of the Geological Society of London in 1872 and with these prestigious credentials became a member of the Brighton Museum Sub-Committee. Edward’s close friend, Thomas Davidson died in 1885 but before then he had trained Agnes Crane in the science of his palaeontological specialty, fossil brachiopods.

Brachiopods are bivalve marine shellfish, similar but unrelated to molluscs like mussels and oysters. They are uncommon now but were very plentiful throughout the geological record. The final editing of Thomas Davidson’s last publication was entrusted to Agnes as the preface records,

Davidson’s extensive fossil collections went to the Natural History Museum in London. Such was the expertise that Agnes acquired, supported by her association with Davidson, that she went on to write several scientific papers on the subject of her beloved brachiopods, published in such learned journals as the Geological Magazine, Transactions of the Linnean Society and Proceedings of the Zoological Society. She also made her own collections.

But it was not in these circles that Agnes Crane was to make her most numerous contributions to science. From about 1878 she published many articles in the popular press, in both the UK and North America, mostly concerned with scientific issues, but on an otherwise wide spectrum of subject matter. These included Cephalopods (octopus, squid, ammonites etc), molluscs, bryozoans, American lakes and Canadian rivers, the origin of speech, fossils and living fish, dinosaurs, and even ancient Mexican heraldry.

She published these articles in a wide range of journals, magazines, and newspapers. In England she published in the Sheffield Independent, (1881), the Derby Mercury (1881), the Morning Post, (1883), the Brighton Herald (1889), and the Women’s Gazette & Weekly News (1889) amongst many others. In America, her writing regularly appeared in the American Naturalist and Science. In these journals, her contributions were more in the style of a columnist or correspondent, submitting articles of interest and communications about scientific progress, events, book reviews etc. Many of these articles were informed by her travels with her father and the contacts she had made. In the American Anthropologist of 1889, the editor wrote,

We don’t have a full list of Agnes Crane’s journalistic publications, nor do we know whether she was paid for her writings, contracts etc.

She lived with her parents until the census of 1901 and remained in the same house until at least 1911 after her parents had died. Her father died in 1901, and probate was granted to Agnes to the sum of £10,254, equivalent to £1.2 million today. She was, at this point, 48 years old and it seems likely that she was financially secure throughout her life.

In the final paragraph of one of her reviews for science (1893), in praising the work of brachiopod palaeontologists, she wrote

And indeed, this collection was completed by Agnes as she foresaw…

We will find out more about Agnes in part two: Agnes Crane, Queen of Brighton’s Brachiopods – Later Life and Legacy.